Although industrial agriculture produces high yields in the short term, it leads to a series of crises in the mid to long term such as the drastic loss of fertile soil, massive decline of biodiversity, and rapid desertification. Because of this many people in Europe and across the modern world are waking up to the fact that we need to start managing the land in different ways.

One important element of this shift in land management is the incorporation of trees, bushes and other perineal plants into our gardens – the widespread adoption of agroforestry in other words. While annual crops (grains and annual vegetables) will likely always remain a large part of the human diet, the creation and maintenance of the conditions that allow us to grow these crops (water, fertility, and biodiversity) has to be integrated into the activity of agriculture itself if modern society is to have a long term future.

Industrial agriculture necessitates huge inputs of water, synthetic fertilizer and pesticides to be viable, so to say that it is possible to raise soil fertility, capture water, and increase biodiversity, all while achieving similar, or greater, yields per hectare, may understandably be difficult to accept for people who are only familiar with industrial agriculture. Fortunately, today there are many working examples that can show just that. In particular, the movement of syntropic agriculture has proved widely successful in this regard, showing that reforestation can go hand in hand with high yield agriculture.

However, this was not the case in the 1970’s. This was rather the era of the ‘Green Revolution’, when governments and multinational organisations were actively propagating industrial agriculture, and anyone interested in ‘alternatives’ had to go far afield to seek them out. However, there has been regenerative forms of agriculture since the earliest times. One famous example of this can be found in the foothills of the Anti-Atlas mountains, on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. In 1975 a young Geoff Lawson visited the village of Inraren and found to his amazement a Garden of Eden like lush paradise.

Despite being situated in arid, desert like surroundings, this valley was cool, humid and abundant in life. Growing on top of one another in a dense jungle were guava, dates, olives, lemon, carob, oranges, quince, banana, mulberry, grape, and many other, grains, veggies, fruits and nuts. Geoff Lawson was so inspired by this food forest that he decided to dedicate his life to agroforestry. He then went on the be a permaculture teacher and writer of some renown, and so his writings on this ancient food forest of Inraren inspired a whole generation of regenerative farmers.

40 years later, I had the opportunity to visit this ancient food forest to see how it is doing today. While I was also taken by its beauty, I learned that environmental and social transformations, particularly huge reduction of rainfall in the last 10 years, have taken a toll on this ancient food forest. However, upon travelling to different parts of Morocco I realised that, rather than being something particular to the valley of Inraren, agroforestry is something embedded in the culture of the Amazigh people, are rather the Amazigh people living in one of the many Oases in Morocco.

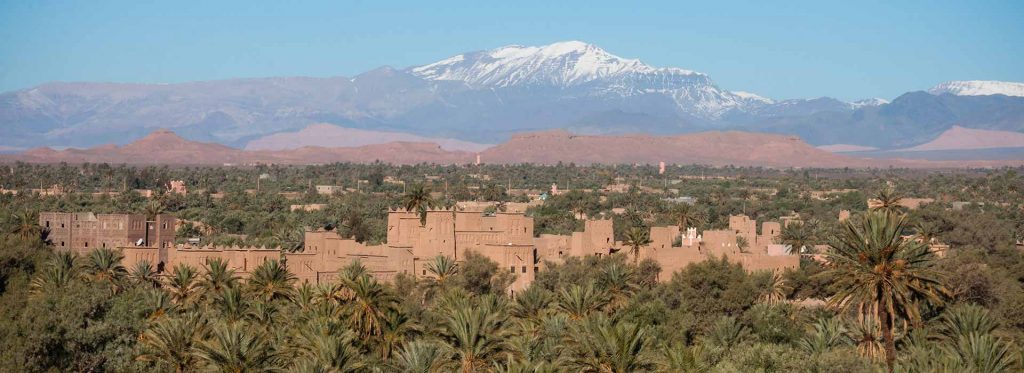

In particular the people of the semi-arid region of Ourzazate, east of the Atlas mountains at the edge of the Sahara desert, practised a highly developed form of agroforestry in challenging conditions; fruits trees of different canopy layers are grown closely together above crops of vegetable and grain, protecting precious water supplies with their shade, with goats recycling organic material to provide fertility to the earth. It is a holistic agriculture that produces a large and diverse yield (enough for total food sovereignty for the local communities) without any industrial inputs, all while having a positive effect on their environment. For this reason, the Amazigh food forests can serve as a source of knowledge and inspiration to a new generation of regenerative gardeners.

Amazigh people

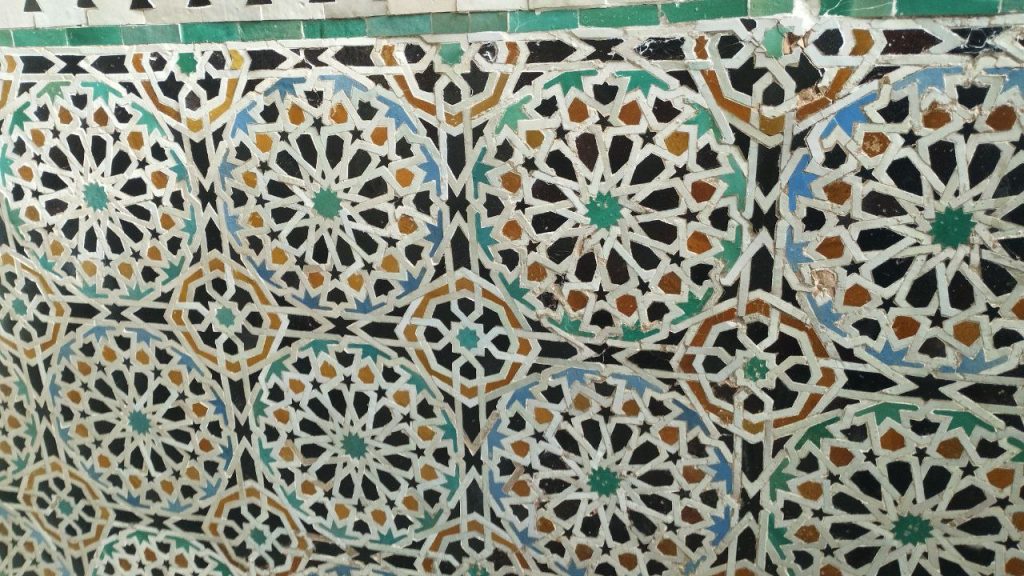

The Amazigh (also known as Berber) are a diverse group of peoples from throughout North Africa, who are connected by language, cultural traditions, and sense of identity. They are dispersed throughout different countries (mainly Morocco, Algeria, and Mauritania), and environments (desert, mountains, coastal, urban), and speak a diversity of related, but generally mutually unintelligible, languages. Their cultural diversity meant that they would not have seen themselves a unified people until the arrival of the Arabs, which brought into sharper relief their similarities. Their cultural lineage can be traced back 12,000 years, and the earliest mention of them is from ancient Egyptian texts. They have their own written script (Tifinagh), as well as rich heritage of arts and crafts (music, pottery, textile), and a striking architectural tradition.

Throughout their history, they have organised in a variety of ways. In ancient times, they were sometimes organised as independent kingdoms, sometimes as tributaries of other States (such as Carthage). In classical times, they were the western most province of the Roman empire, before being invaded by the Goths, and then the Arabs. It was the Arab migration that would have the most profound effect on the Amazigh people, leading to the widespread adoption of Islam and the Arabic language (today about 35-40% of people in Morocco speak an Amazigh language, with 90 – 95% speaking the local dialect of Arabic).

They would not remain part of the Arabic political empire for long though, with the region of Maghreb breaking off into a series of regional kingdom, which eventually coalesced into a series Amazigh empires like the Almovids (1050s – 1147) and the Almohads (1121-1269) ruling over large parts of North Africa and the Iberian Penisula. After the fall of these empires the Maghreb remained largely independent from encroaching colonial powers for the next centuries, before being divided up between France and Spain in 1912. The various countries that make up the Maghreb region then again achieved independence in the mid 20th century.

Despite centuries of cultural and political marginalisation by governments looking to enforce a policy of ‘Arabisation’, today the cultural identity of the Amazigh remains strong. In recent times, there has been a cultural revival and increased recognition of the importance of Amazigh tradition and culture for the local region. It is also important to remember that being ‘Amazigh’ means different things to different people. At its base, it means tracing ones cultural lineage to the pre-Arabic people of the Maghreb (and some other pockets of North Africa), and speaking a Berber language. For those closer to their roots, it also means a way of growing food, building, making textile, and other art works.

Inraren

The first Amazigh food forest I visited in Morocco was the famous Inraren, visited by Geoff Lawson 40 years previously. The village is located in the foothills of the Anti-Atlas mountains, a one hour drive from the Atlantic coast. Here the land is dry and the most biotope can be described as an Argan savanagh. The Argan tree, as well as providing a source of income to local communities in the form of valuable Argan oil, is also essential in preventing the spread of the Sahara and further desertification of the region. Argan are highly drought resistance trees, and can withstand temperatures of up to 50 degrees. It is today relatively unique to the region, now only growing in southwestern Morocco. Aside from Argan, the main other plants you will see growing are cacti and hardy perennial shrubs.

The valley beside Inraren is known as ‘Paradise Valley’ and is a big tourist attraction. Here you can jump into beautiful cascading pools of water, or eat in one of dozens of restaurants which have crowded around these pools to cater to tourist. It got its name from the first wave of tourists who arrived in the 1960’s, the hippies. One local restaurant owner, who told me that his Dad opened the very first restaurant in the valley in the 1970’s, said ‘the hippies were dirty people, but they kept everything clean. Today the people who come are clean, but make everything dirty’, and it was true that there is quite a bit of litter strewn around the valley. ‘Today it is more like ”Hell valley”’, he said, half jokingly. You do get the feeling that the name ‘Paradise Valley’ was probably better suited to the place before they built the concrete road to facilitate the many bus loads of tourist arriving every day, and before tourists blasted music from their powerful speakers to better enjoy the tranquillity of the mountains.

While there is some agroforestry happening around Paradise valley itself, it is in Inraren, about 7km away, that you can find the huge ‘Palmeraie’ (named after the huge palms that tower over it) that so inspired Geoff Lawson. Inrarn is a small town of a few hundred inhabitants, situated on the hillside overlooking the Palmeraie, which remains a beautiful sight to this day. From there you can see hundreds of date palms poking out of a dense forest.

Upon entering the Palmeraie you get that beautiful feeling of being somewhere lush, cool on a hot day, humid in a parched desert. The white hot sun turns green and you find yourself at ease. Its clear why, arriving in 1970’s, when there was almost no agroforestry happening in Europe, this feeling would so inspire someone interested in regenerative agriculture.

The forest is divided into many different plots, which have a large degree of variation in management. Some plots are lush, with field of fava beans, bananas, lemons, olives and palm, ensuring a complete crop and canopy coverage. Others lay fairly abandoned, or dried out. Some looked lightly managed, with clearing and harvesting happening but nature also being given a lot of space to express itself. This diversity of management gave the place quite a wild feeling, and showed nature working in a variety of ways in accordance with the type of co-operation of human beings.

I would say that the most common type of planting was; dates as emergent level of the canopy (almost always), with argan, olive and carob occupying the high level, and pomergranate acting as a mid level and sometimes fava beans as ground cover, and grape as a vine. Less frequently, there was also fig, loquat, oranges, and bananas, with mastic and tetraclinis articulata being local plants that were also occupying space in the garden. Tree were sometimes planted very densely, other times there were large clearing that allowed for the planting of annual crops. However these annual beds were often bare when I saw them. This was partly because it was winter (mid-January), and it was only possible to grow fava beans or some brassicas anyway, but it was also because of changing weather patterns in the last 10 years (more on that below).

Perhaps the key element of this food forest is water management. Inraren is surrounded on all sides by desert conditions, the intense summer heat and bare rocky soil ensure only the hardiest of desert plants can grow here. What allows the valley of Inraren to flourish are underground springs that are then carefully channelled throughout the valley to maximise the capture water by living organisms. This is achieved in some places with the traditional technique of dug earthen channels, and others by concrete channels (the earthen technique has the advantage of more seepage of water into the ground, increasing plant life at its borders, the concrete technique has the advantage of requiring less maintenance). In other places channels are built up using fallen palm trunks, or other organic materials. The creation of terraces throughout the valley also prevents erosion and creates more spaces for the water to seep into the ground. The water is collectively managed by the community, with each family being allocated a certain amount of water each week.

Amazigh people have long history of skilful water management. In Al-Andaluz, now Andalucia in the south of Spain, many of the irrigation systems that act as the only lifelines for many communities across the region, were built by Amazigh engineers more than 500 years previously. Acequias (from the Arabic as-saaqiya) are irrigation systems that use gravity to channel water from natural sources into people’s gardens. They are composed of a series of main and secondary canals, as well as water storages, such as pools or cisterns. These acequcias systems were often carved into rock, and so stand the test of time, although many of the water sources are today going dry because of excessive pumping of ground water by the agro-industry.

As I was walking through the Palmeraie, I met a friendly farmer named Hasan. He told me a bit about the food forest and one of the things he mentioned is that the rain has dramatically reduced in the last 10 years. Before, there was enough water to grow grains and a lot more banana and citrus. All the beds were fully planted, and there was a large harvest of annual crops. Now the main harvest is of the drought resistant trees, date, olive, argan, carob. The seasonal rivers have run dry and the pools of water have started to dry up. Water must now be carefully rationed to ensure any harvest whatsoever.

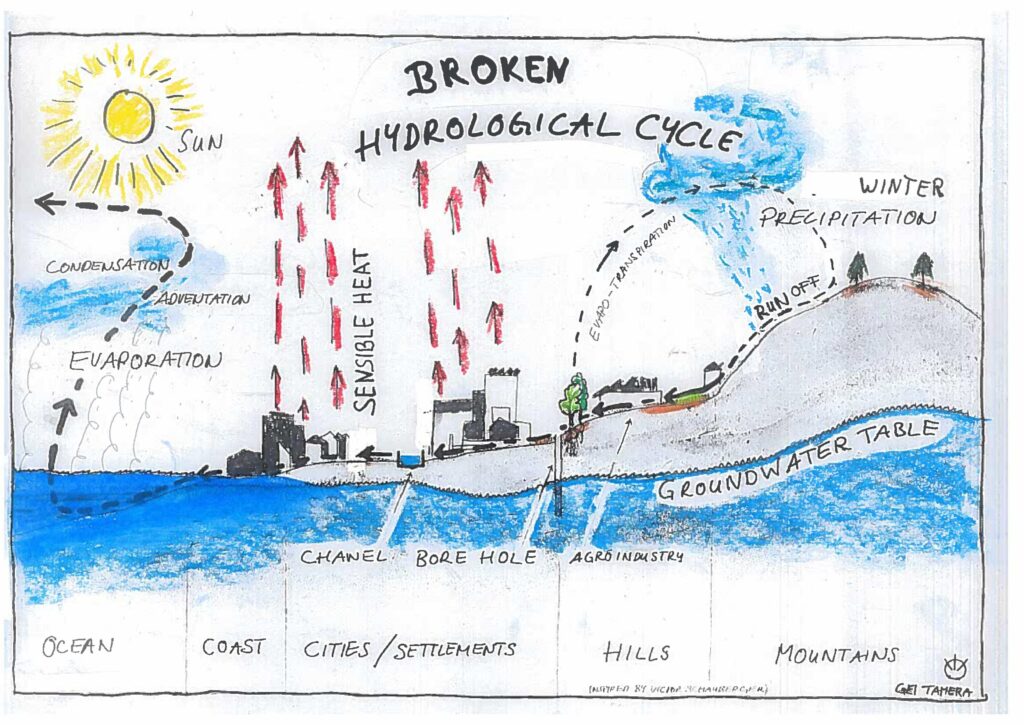

What is happening? Well, changing weather patterns involve a huge variety of factors. It could well be that rising global temperature levels are having an effect. Another reason could be a break in the primary link of the water cycle. The drastic decline in rainfall coincides with huge urban development on the coastal area around Inraren. With coastal towns like Taghazout becoming internationally known surfing locations, huge resorts have sprung up all around the coast. This urban development has meant deforestation and urbanisation.

This is a problem because, although the water cycle begins in the sea, with coastal winds blowing evaporated sea water onto land, once on land, plant and fungal life play an essential role in making that rain fall. Trees slow winds, and the innumerable fungal spores floating above forests clouds condensate, bringing the rain. Afterwards, trees play an essential role in cloud formation on land, transpiring stored water, releasing moisture, allowing that water to travel further inland. If there are no trees, and a layer of concrete where the soil should be, you have increased water run off, erosion, no transpiration or cloud formation, and a water cycle cut short.

Hassan told me that another problem for the agroforestry system is that there are less and less people to work them every year. In a pattern seen across the world, young people migrate to cities in large numbers for education and work, and many of the people who remain now seek to make a living from Paradise Valley tourists. In the 1970’s, the forest was apparently worked by around 800 people. Today that number is significantly reduced. Without anyone to manage the plant life, and maintain the irrigation system, the agroforestry system cannot survive. This is still a long way from happening, much of the agroforestry system was still being worked when I was there, but the process has begun. It is compounded by declining rainfall, as the life of the farmers become less certain and harvests decline.

Having only heard of the agroforestry systems of Inraren, I was somehow under the assumption that it was something localised or unique to the valley. So I was very happy to discover, upon travelling to the region of Ourzazate at the edge of the Sahara, that agroforestry is widespread among the Amazigh people of the Morrocan Oases. In the Oasis of Skoura and the Gorges of Dades and Todhra, I witnessed huge agroforestry systems, growing in far more favourable conditions than Inraren.

Oasis de Skoura

The Oasis of Skoura is located about 40km east of the city of Ourzazate. It is a relatively small town, that gets some tourism for its well maintained kasbah (traditional fortified clay home) and its massive Palmeraie. Around 4500 families work its approximately 2500 hectares. The crops grown were similar to that of Inraren: dates, olives, almonds, pomegranates, figs, beans, and kale, all of which I saw in Inraren, but here there were some differences. The most noticeable was that many fields had small blades of wheat growing in them, along with quite a lot of fava beans and other grasses for fodder for goats. In summer I was told there is a also a crop of barley, lentil, artichoke, chickpea, tomato, onion, carrot, and zucchini.

This is because the water supply here is generally better than in Inraren. Although there has been relative drought the preceeding three years, 2024was ok in terms of rainfall. This creates seasonal rivers (known as wadis), which add to the water supplies coming from underground aquifers and melting glaciers. This water supply is then carefully channelled through the landscape in the typical manner (here the irrigation channels are known as khetteras).

Gorges of Dades and Todhra

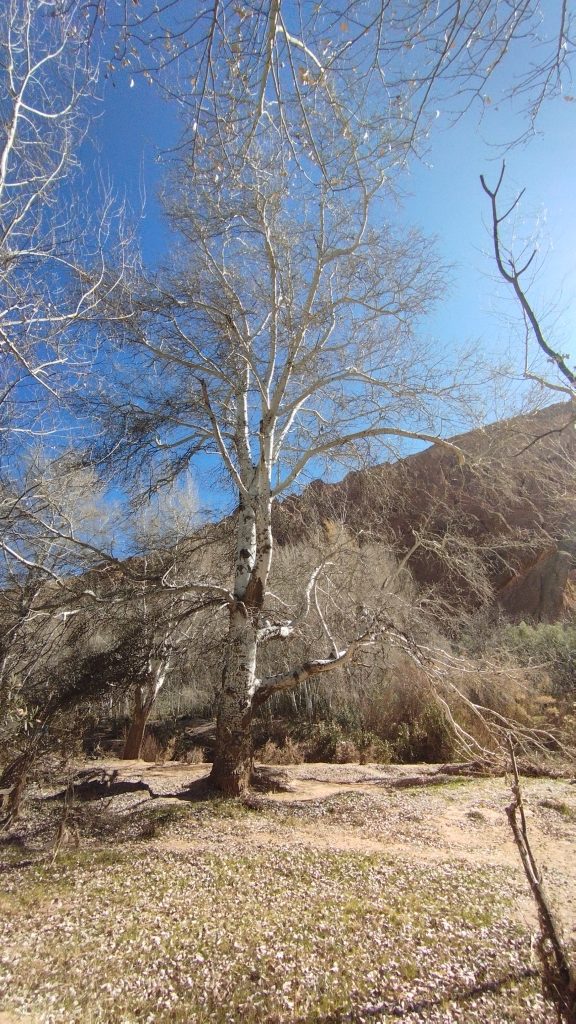

Up in the mountain valleys, things were even more abundant. I visited two villages in the foothills of the Atlas mountains, both beside large mountain passes leading up to the high mountains. The first was the village of Tamellalt next to the Dades Gorge. Although it is quite close to Skoura (about 80km away), the biotope is quite different. This is understandable as it exists under very different conditions. It is about 500 meters higher than Skoura and its location within a valley means it gets considerably less sunlight hours. It also exists on the banks of a permanent river. Here there are no date palms, and white popular dominant the landscape. Their huge white trunks and white leaf litter, make all other colours stand out and creates quite a unique chromatic experience.

Here the main crops were not dates and olive, but walnut and fig. There was also a lot of roses being grown, to be turned into rose products that are somewhat of a speciality in the region. Along with the roses are a huge variety of other medicinal herbs, and in general in Morocco there is a thriving culture of herbalism. Many people have knowledge about the medicinal properties of plants, and all towns and villages have at least one herbarium, with large variety of medicinal plants and medicines produced using these plants.

The clearings for annual crops were much larger than in Skoura or Inraren, and there was a lot more work put into the terracing, with many of the terraces being built out of stone. But aside from these differences, the basic elements were the same; mixed dense forest and fields annual crops, with a variety of animals also present (goats, chickens, donkeys).

The last large scale agroforestry systems I visited were in and around Todhra Gorge, famous for its huge limestone cliffs which were carved by the Todhra river over many centuries. Here I visited two distinct agroforestry systems, one upstream along the riverbanks of a narrow valley, the other downstream in a wide open valley plain. Downstream it was a similar agroforestry system as that of Skoura and Inraren in terms of crops; dates, olives, figs, pomegranates, etc. The main difference was that here there were some huge areas dedicated to annual crops such as wheat, barley and corn, areas much larger than in Skoura or Inraren.

This made possible by the greater abundance of water, as the Todhra rivers flows through the valley throughout the year. Throughout the Moroccan oases, there is a clear correlation between the amount of water available, and the amount of annual crops. When water is more scarce, people tend more toward densely planted perennial systems with small shaded patches of beds for annual crops. When water is abundant a much larger proportion of the land is dedicated to annual crops.

One thing that was interesting for me was the fact that the vast majority of plants in the system were crops. Trained in syntropic agriculture, we usually try and keep a balance between crop plants and plants that are there to produce biomass to feed the soil. These plants would be regularly pruned and their leaves and branches placed on the ground. But here the people planted almost exclusively crop plants, and the fertility came from goat shit, alfalfa, and the river, which brings fertile silt and clay from upstream. This constant supply of fertility is one reasons why riverbanks are the most important centres of agriculture throughout the world.

Upstream things were a little different, the main difference being that there was no palms. I don’t know if this was because palms weren’t as suited to that part of the valley (it was only about 4km away but the narrowness of the valley meant that there was less sunlight hours), or a community decision. Here I saw many people out working or chilling in the fields. They were mainly planting alfalfa to improve the soil for the upcoming spring planting season, and for fodder for the goats. Walking around I was really struck by the idyllic nature of the agricultural activity. Surrounded on all sides by mountains and trees, in the light of day, on the banks of the river, working with the earth. Alhamdulillah

Oasis Agroforestry

The ‘Oasis Theory’ was posited in the early 20th century as one explanation for why people started farming. The idea is that people were forced into oases because of changing climatic conditions, and it was these people, living in a relatively closed ecosystem, who first began closely co-operating with plants and animals in a way that can be described as agriculture. These people then eventually left their oases and brought farming to the rest of the world. This theory is not widely regarded anymore, but it does point to the unique conditions of agriculture in these isolated ecosystems.

In a little island of life surrounded on all sides by desert, there is little choice but to ensure that the ecosystem you depend on flourishes, and to make intelligent use of natural resources. As one person in Skoura said to me, ‘when there’s no water, there’s no water’. One feels the effects of environmental degradation almost immediately. This is unlike more favourable temperate climates where land degradation takes many years or even generations. This observation is corroborated by the fact that the Amazigh people of the more fertile and temperate northern parts of Morocco practice conventional degenerative agriculture, tilled monoculture.

Because the processes leading from abundance to scarcity take so long, it is hard for people to realise the effects of bad agricultural practices. This is obfuscated even further by industrial agricultural practices, with which one can produce a yield on land that has long since become essentially devoid of life. The people of the Oases don’t have this ‘luxury’. Another mitigating factor for soil degradation is conquest. If your society is running out of fertile soil, you invade your neighbours to take advantage of theirs. According to the work of David R. Montgomery in Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations, this pattern has been repeated throughout history and will likely continue unless we clearly recognise and rectify its causes.

Kasbahs and Amazigh Natural Building

While I wasn’t expecting agroforestry to be so embedded in the traditional Amazigh way of life (or at least in the life of the people in the oases between the Sahara and the Atlas mountains), I was expecting to find a strong tradition of natural building, as Morocco is rightly famous for it. The country has a diversity of traditional architectural techniques. One particularly interesting technique is tadelakt. This is a type of smooth plaster made of lime, sometimes with the addition of limestone or marble sand, that is then polished using a smooth stone and olive oil soap to make it water repellent. The smoothness of it has a calming effect and because of its water repellent qualities it is often used for bathrooms or traditional hamans. You can also add a variety of pigments to colour it, such as blue or red.

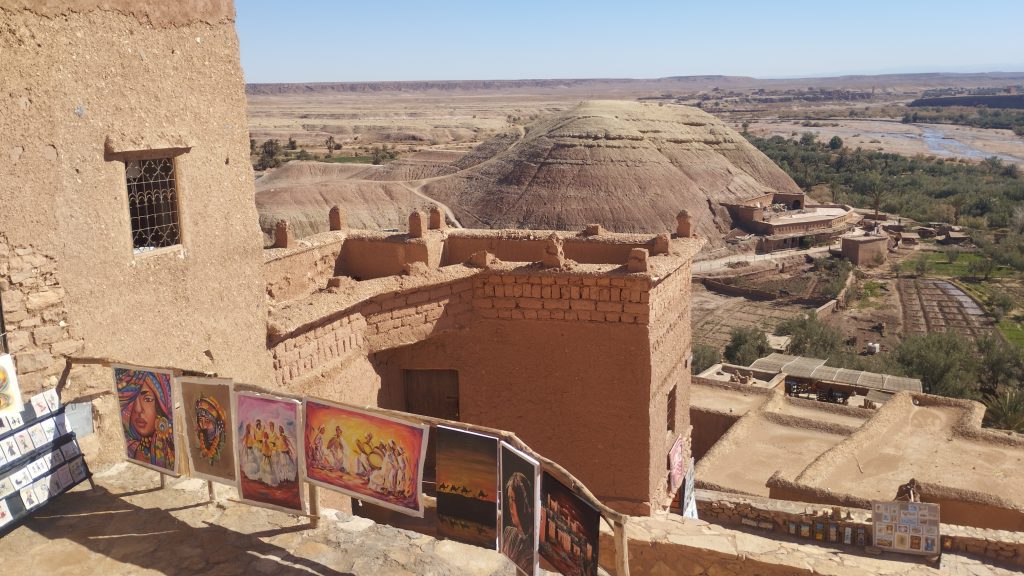

The type of natural building we will look at here is that found in the oases regions we have been talking about, ksours and kasbahs. Ksours are fortified earthen villages composed of homes with closed courtyards, granaries, mosques, and other communal spaces, all connected by a labyrinth of narrow passageways. They also served as fortifications and so have a variety of defensive structures, such as high walls and corner towers, and were generally built on strategic locations like hilltops. A kasbah is similar but was generally owned by a single ruling family, while a ksar (singular of ksour) was for a community composed of a number of families. These types of structure date back until at least the 11th century, and were still being constructed until the early 20th century. Many of them today lie in ruins, but some of them are still being maintained and are a beautiful example of ancestral natural building.

The main material being used is earth, stone for foundation, with some palm, cedar or other local timber also used. The main techniques are adobe and compressed earth. To compress the earth they use wooden boards as a kind of mould and a wooden mallet to really compress it well. They use no special mixture of earth, simply use what is close at hand. For the adobe, they use earth with a particular ratio of clay and sand (they find a place where the earth is the correct ratio rather than combining different types of earth), and small wooden frames to mould it into bricks and leave it in the sun to dry. Adobe bricks will then be lain and plaster over with earth or lime plaster.

What I was impressed by was the sheer amount of earth used in the construction. Its mass must have been at least 80% earth. In Europe, because of better access to timber, the vast majority of traditional house have timber frames. But the ksour have no frame at all. The earthen walls act as the structural support for the roof. The only wood used is for the beams, rafters, decorative elements, and sometimes lintels for windows and doors (although they also often used arched adobe bricks for that too). The roofs were made of palm or cedar for the beams and a few sparse rafters, then a layer of tightly bound cane, and a layer of earth, making a beautiful flat roof that also serves as a roof terrace. The amount and density of earth used makes it incredibly well insulated, warm in winter and cool in summer, essential for life at the edge of the Sahara. The one downside of this amount of clay and a flat roof is that it requires regular maintenance, once a year or after particularly after heavy rains.

Coming from Europe, I was interesting to see a fortified structure without a castle at its centre. At the top of the hill at Ait Ben Haddu, one of the best maintained ksour, there was a granary where the castle would have been in Europe. This because the ksour weren’t owned and lorded over by a king or ruler, but was rather a community run enterprise, which was largely autonomous in their own government. Although they were sometimes part of a larger political entity (such as the Almohad empire), in practice this only meant paying taxes or sometimes sending people to work as soldiers.

This does not mean that their government was entirely horizontal. Rather authority was given to people based on their sex, age, kinship ties, and perceived ethical virtues. The ksour were governed by a council of elders (Jamaa), composed of elders from important families, or respected members of the community. Within these councils decisions were made through a process of deliberation and consensus finding, based local tradition, custom, as well as Islamic law. Living in a ksar would have come with certain responsibilities. Along with being responsible for the upkeep of their own homes, all families would have also been expected to the maintenance of communal structures, like granaries, mosques, or defensive walls.

The economy of the ksour were based around the aforementioned agroforestry, and crafts such as weaving, pottery or metal work. They would have been autonomous in all the most essential elements of their economy (agriculture, construction, textile, pottery, etc.), although they were integrated into extensive trans-Saharan trade networks, and were often located on important Saharan caravan routes for exactly this reason. Many ksour also formed alliances with neighbouring ksour concerning defence, water rights, or infrastructure.

Today, as in most part of the world, these traditional practices, both architectural and organisational, have become marginalised. The Jamaa does still exist in some places, with positions of respect in their communities, but with no formal governmental authority. Instead, the people of the Ksour are governed by the King of Morocco, who, upon gaining independence, in true modern style, centralised all functions of government to a tiny ruling body in the capital with a huge bureaucratic apparatus.

The traditional building style has also greatly receded. While some people do still build using the traditional earthen techniques, most in the towns and villages around the palmeraies and ksour are built with concrete, or other pre-fabricated materials. The reasons for this are most likely because the earth techniques are marginally more labour intensive, the annual necessity to re-plaster the earthen houses, and because a concrete house is often seen as a mark of modernity, and so somewhat of a status symbol.

Unfortunately, modern houses, as well as greatly polluting the environment when they do wear down in a few decades, are far less adapted to the local conditions. Boiling hot in the summer, freezing in winter, requiring huge inputs of energy to be habitable. One day, when the conditions that allow for the erection of these buildings pass away, people will return to building house in harmony with there surroundings. When these people look upon the ruins of these modern houses, piles of concrete, steel, and polystyrene, they will probably wonder why anyone would expend so much energy to transport these materials to the desert to build a house.

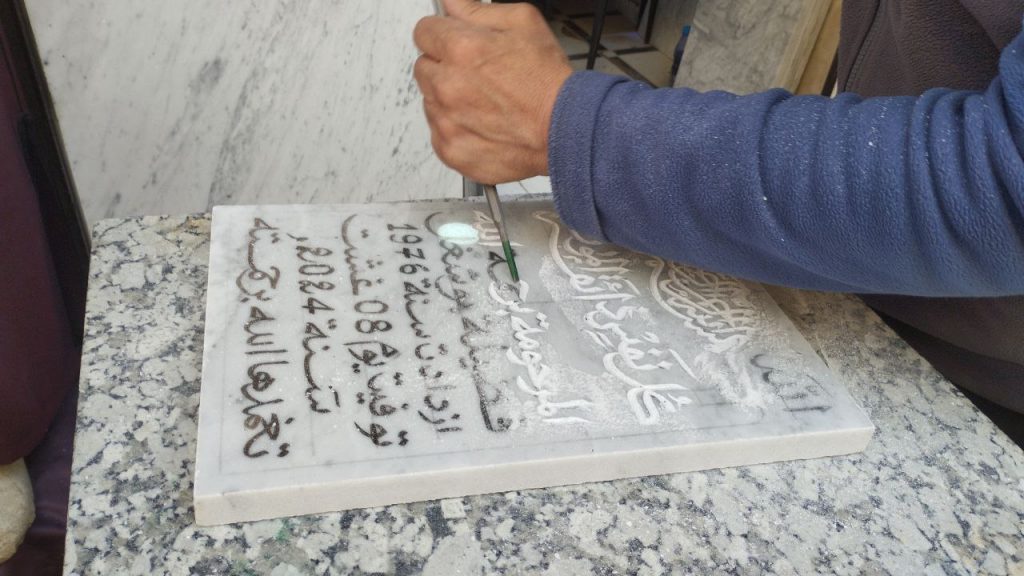

Artisan Culture of Morocco

The final thing I would like to mention is about the strength of the artisanal economy in Morocco. Since the growth of the industrial economy most parts of the world have seen a massive decline in local arts, crafts and production. This is both because of greater productive capabilities in industrial factories, as well as deliberate colonial and post-colonial economic and trade policy. For example, when it was clear that factories in Manchester couldn’t compete with Bengali weavers, the British introduced restrictive tariffs on Indian goods to cripple the local economy, and went so far as to break the hands of Bengali weavers to enable to growth of the British industrial economy. Today Bengal is again one of the main global centres of textile production, but the economy is controlled by industrial multi-nationals, rather than local artisans.

Despite the efforts to promote the global industrial economy, the local artisan economy still survives in many places around the world, and Morocco is certainly one of them. In the narrow streets of Fez, Marrakech, Chef Chauen, Essouira, and many other places, you can still artisans engaged in all manner of crafts; weaving, leather work, copper work, ceramic, masonry, painting, carpentry, etc. Many sold their wares directly from their workshops, or else, those who weren’t on busy streets, would give to a merchant to sell. The advantages of this kind of production or industrial factory production are manifold.

In the first place the artisan benefits by having a job in which they can direct their own energies and express themselves creatively. In this way the craftsman doesn’t become alienated from their activity or from the fruits of their activity. It benefits the person buying the object because they get a hand crafted unique piece, rather than a pre-fabricated mass produced one (although this is admittedly subjective). On the level of economy, there is no exploitation happening (in the Marxist sense of exploitation, whereby those who own capital profit from the labour of others). The artisan brings their goods to the market themselves, or gives it to a merchant to sell for them, who takes a proportional part of the profit for their work in selling. Therefore those who create the goods, or put their time and energy directly into selling it, see the proper return for their labour. This is unlike in industrial production, whereby the vast majority of profits go to corporate managers or shareholders, and the people who make the goods sometimes barely receive enough to feed themselves.

In Morocco, one thing I also noticed was a large number of women’s co-ops. These are organisations founded by a group of women, generally from a number of different families in a town or village, who would pool their resources to sell their wares, such as rugs, Argan oil, or backed goods. The profits would then be shared between all the women involved. These co-operatives give these women an independent source income and a collective activity outside of their own households.

Another advantage to artisan economy is the strengthen of the local economy. Industrial production generally has the effect of exporting wealth from their centres of production. This is because, as mentioned, those who produce the goods only receive a small part of the profit generated by the goods. Instead, the wealth flows to wherever those who really profit from the production (the CEOs, shareholders, managers,etc.) reside, places like Paris, New York, London, or ends up accumulating in bank account of the hyper wealthy. Goods that are sold locally by artisans or merchants bring wealth into local economies, which then circulates locally and enriches ordinary people.

Despite all these clear advantages, many people still see artisan economy as a relic of a bygone era. This is because of the advantages of productive capacity of industrial production. A factory worker operating industrial machinery will be able to produce goods much quicker than an artisan, and the industrial goods can therefore be sold at a rate that the artisan cannot compete with. In a world in which one only thinks of short term profit, what can be the advantage of artisan production?

This feeling transcends political divide. Karl Marx’s theory of historical materialism ranked societies according to their productive capacities, with industrial society being an evolutionary stage higher than artisan production. However, a quarter of the way through the 21st century, it is time to start asking ourselves how efficient is industrial production? It is certainly efficient in generating profits for a small number of people. But in terms of resources, it is now clear how incredibly inefficient it is.

An artisan who produces an item of clothes using locally produced materials; spinning, weaving, and tailoring using simple and appropriate technology; and selling the goods locally, has a minimal effect on their environment. In contrast, a textile corporation, who ships petrochemicals from one side of the world to the other, to be turned into synthetic fibres, which is then spun, woven and tailored using heavy machinery and other strange chemical, and then ships the finished product all over the world to be sold has a huge environmental cost and necessitates a huge input of resources. How do we imagine the later to be more efficient than the former?

Of course some things necessitate industrial production; trains, computers, internet, etc. But some things, the basic necessities of human existence (textile, construction, ceramic, woodwork, etc.), it make more sense to produce in an artisanal way – giving people meaningful and creative life activities, giving space for a proliferation of local styles and culture, revitalising rural economy, making effective use of the finite resources we have on earth (allowing us to save those resources for things we actually need them for). Morocco is one place which can serve as an example to the rest of the world as a thriving centre of artisan production.