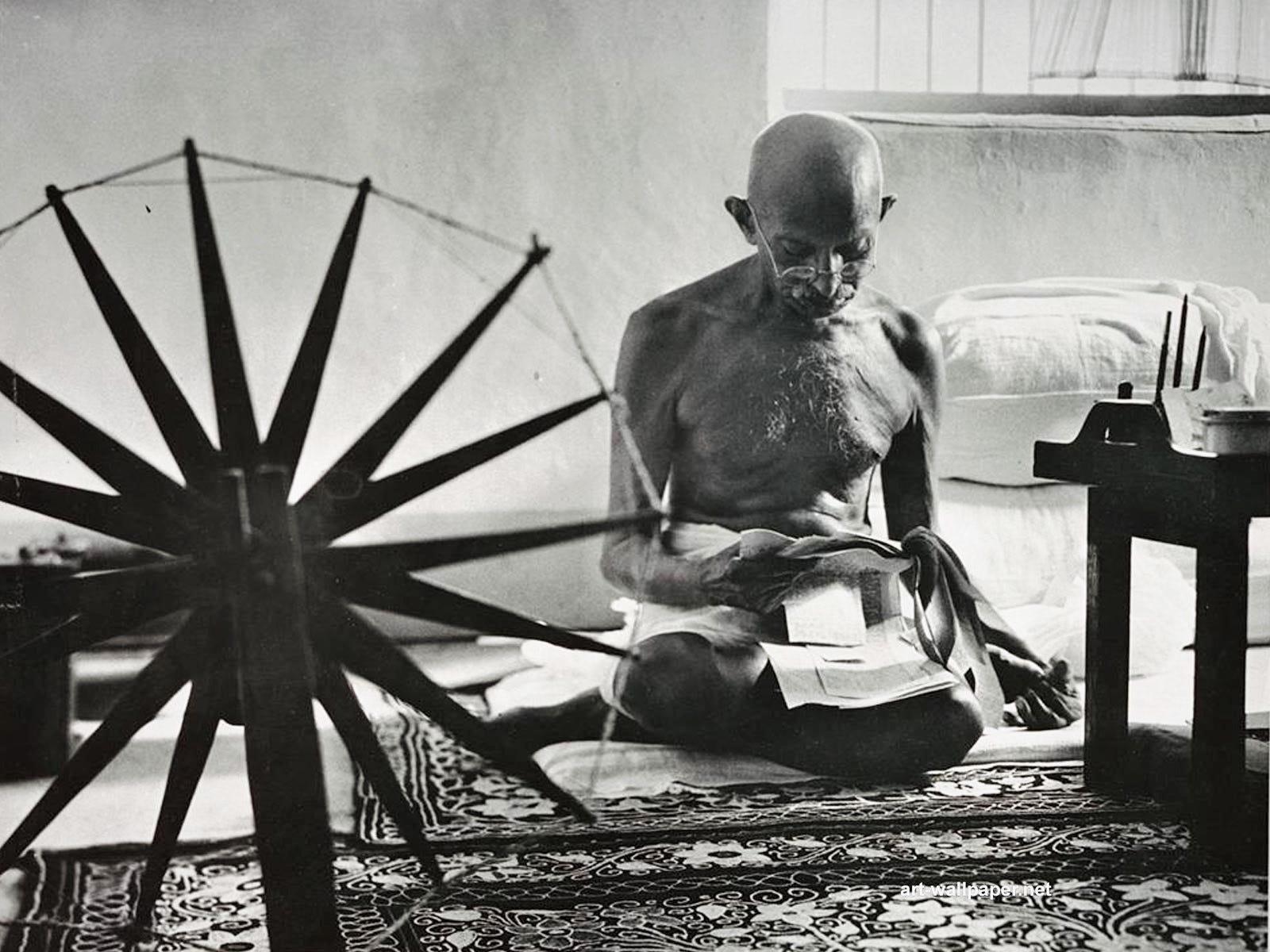

What awoke my interest to the idea of community as a platform for social transformation was studying the politics of Mohatma Gandhi. As opposed to most other political movements, which try to effect change at the level of the State, a top-down approach to politics, Gandhi’s approach begins with individual and community transformation, and used these as the foundation for wider social transformation. Another key element of Gandhi’s politics was connecting the fields of politics and spirituality, acting from the understanding that the political struggle was simultaneously a spiritual struggle, and vice versa. This is in contrast with most left political movements, which have purely material aims. But in a time when those of us inside the empire of modernity have access to abundant material wealth, but suffer from a kind of spiritual poverty, this kind of politics made a lot more sense to me. After coming to these conclusions, about the kind of social movement that is called for at this moment in history, I realised that such a movement already existed – that thousands of people had come to the same conclusion and had already begun setting up communities based on this understanding – beginning my journey. And while many of the communities take some kind of inspiration from Gandhi, I was excited to see that there was network of communities that explicitly sees itself as part of Gandhi’s political lineage. Most of these communities, including the original, are in France. But there is one to be found in Germany, Friedenshof – about 25km north of Hannover. And at the turn of winter into spring, I went to stay with them for a couple of months.

History

As just mentioned, the Communities of the Ark trace themselves back to Mohandas Gandhi. Gandhi began his political career in South Africa, where he organised Indian migrants against racist laws. Central to the campaign was that the political resisters would not use violent force. Instead Gandhi sought to cultivate another force, satyagraha, the force of truth and compassion. For Gandhi, ahimsa (non-violence) was not only a political strategy, it was an end in itself – the way to creating a better world. Fortunately, as a political strategy it also proved very effective. The British colonists, who were more used to dealing with violent resistance, didn’t know how to respond to Gandhi’s satyagraha campaign, and pretty soon the racist laws were rescinded. Upon returning to India, Gandhi began to organise satyagraha campaigns against British colonial rule on the subcontinent. After returning to his homeland after 20 years of absence, Gandhi quickly became the undisputed leader of the Indian independence movement, and rallied millions of Indians behind a campaign of non-violent resistance to British rule.

But resistance to British rule was only a small part of Gandhi’s political vision. Far more important was the empowerment of people on the local level. Gandhi saw how the British had not only set up a political empire in India, but also an economic empire. To support the growth of factories in Manchester, they had destroyed much of the local textile production that had existed in India since ancient times. This not only impoverished the once wealthy Indian village, but also made millions of Indian dependent of the global markets to clothe themselves. Gandhi saw that this dependence meant poverty and destruction for the Indian village and so he travelled the length and breath of the country with the charka, the spinning wheel, empowering people to once again be able to clothe themselves, and thus be independent from the colonists once more. For Gandhi, only this could be considered swaraj – independence, self rule. His argument was that if Indians were dependent on the colonisers to clothe themselves, or feed themselves, or for any other basic necessities, they could not consider themselves ‘independent’, no matter what the independence leader achieved. Replacing the British rulers with Indian rulers was not Gandhi’s aim, it was rather to empower people to rule themselves. His vision for a better society was Panchayrat Raj, rule of the village community.

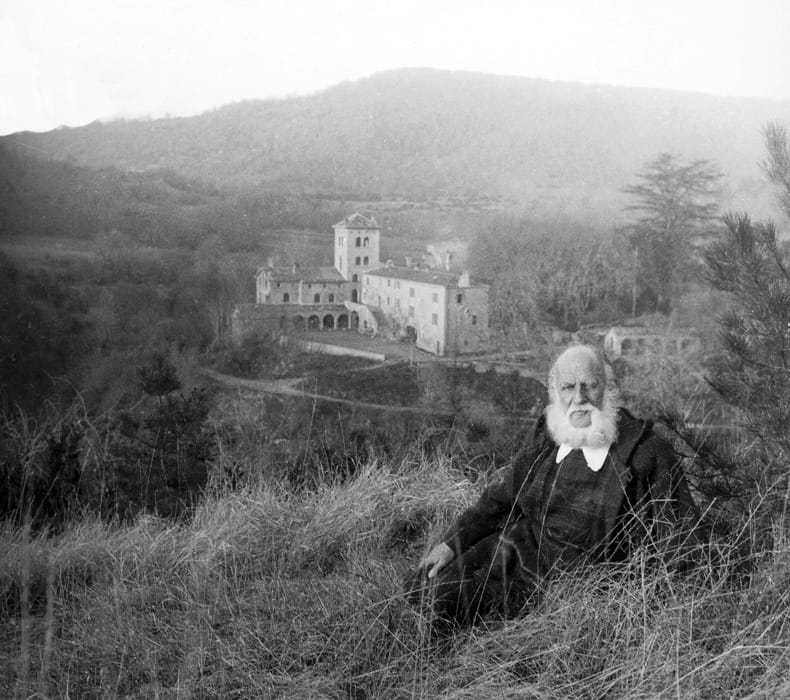

In 1936 French peace activist Lanza del Vasto came to India to join Gandhi’s Satyagraha campaigns. After four years by his side, he came back to Europe intent on bring Gandhi’s philosophy and political tactics back to Europe. In 1948 himself and his wife Chanterelle founded the first Communauté de L’Arche (community of the ark) with a number of other peace activists. In the beginning, the community organised its life closely after the model of Gandhi’s ashram – no personal property, simple modes of living, a lot of time dedicated to spiritual practice, autonomous (not only economic, but also in terms of education and justice). After a few years, following the arrival of new members, some of these rules were relaxed, but the basics ethics remained the same. Central to the philosophy of the community, as in Gandhi’s ashrams, was that it not only functioned as a space of creation, but also one of resistance. Community members took part in various campaigns of non-violent political struggle; against the Algerian war, the building of nuclear power stations, the expansion of military base on community land.

After a few years, the model set down by the Communauté de L’Arche began being taken up by others. However, the history of the movement is long and complex, so we don’t need to go into it here. To summarise, communities started springing up in other parts of France, as well as Canada, Italy, and Spain (many of which failed after a few years). At one point the number of communities was 15, but, for a variety of reason, many of these projects were discontinued after a few years (the current number of community houses at five). Many of these projects began in the late 80’s, including Friedenshof. In Hannover, three activists (Karston, Bärbel and Uli) involved in the peace movement decided that; ‘political actions weren’t enough. We wanted to go deeper into our own non-peaceful patterns of behaviour, as well as transform our daily lives, our work, and consumption, so that it contributes more to peace, justice and the conservation of creation. We also wanted to give spirituality a fixed place in our day to day lives. In the French arch communities we saw that they had, to a large extend, realised such a vision, and so we made a plan to start our own community in Hannover inspired by the same model.’

In 1989 they wrote up the ‘Rule of Friedenshof’, a statement of intent for how they wanted to spiritually organise their lives (largely inspired by the rule of Benedict, Taizé, Thich Nhat Hanh, and the arch communities). Although called the ‘rule’, it was not a strict set of rules or proscriptions, rather a guideline for how the community wants to live together – with each individual to decide for themselves how to best apply these guiding principles. In 1990 they found an old farmhouse in Niedernstöcken, and with a few loans from friends, could quickly snap it up. In the beginning there were 8 adults and 5 children, but barely enough space to accommodate them all. The community members quickly made themselves familiar with the techniques natural building and began renovating the barn and farmhouse. As with the vast majority of communities, the extension of the years saw a variety of crises, reconcilements, and new beginnings. Old things come to end, new things begin, then pass away themselves. The communities that stand the test of time are the ones that can adapt to these changes. And in the past three decades, Friedenshof has proved up to the challenge. The current number of permanent members is 6, with 6 other medium or long term members. On top of that are a lot of other ‘friends of the community’, who come and stay for a few days (or more) at a time, as well as a constant flow of volunteers.

Space

The community house is in the small village of Niederstöcken, about 25km north of Hannover. Upon entering the grounds, the first thing one sees is the beautiful thatched roof of the main building. Thatching was once the most common method for putting a roof over your head across northern Europe. It’s advantages are numerous; the low cost and availability of the material, its ability to resist harsh weather conditions, its lightness – meaning less timber is needed for the inner roof, its versatility – meaning that it can fit to any shape you want your roof to be, the fact that it is densely layered, trapping air, and thus acting as insulation as well as shelter. For these reasons thatching is still the most widespread method of roofing in the world today. But the dawn of industrial manufacturing has meant the disappearance of all but a few of these fine examples of natural building in much of Europe, making every encounter a treat. Sitting snugly below the thatched roof is an almost 300 year old farmhouse that is also a beautiful example of pre-industrial German architecture. The Fachwerk Haus is the traditional German form of timber framing, using wood as the structural framework for a building. Wooden beams are connected by a series of joints, and the space between the beams is filled with a variety of material (generally clay, bricks, or stone). This ancient method of building requires no foundation as the framework bears most of the load of the house (although its best to place the wooden framework on a bed of stone to prevent rot). The Fachwerk Haus is a highly celebrated tradition in Germany, and the community house of Friedenshof is a beautiful example of it.

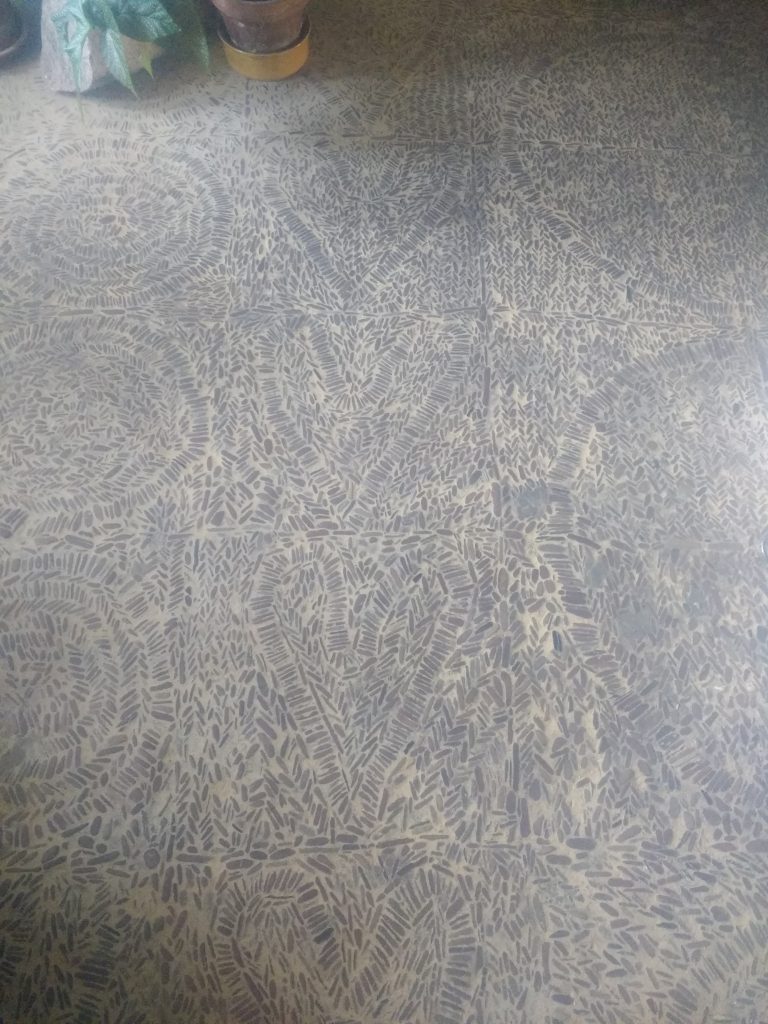

The front entrance this building leads into the Flett, a huge multi-functional dining room where a lot of the community life takes place. Entering the house through the Flett gives you an immediate sense of the 300 years of history that it has behind it. The mammoth wooden beams that hold up the top of the house have clearly been worn away and restored many times. The stone floor is the 300 year old original, upon which patterns of the past can still be made out – a Latin inscription reading ora et labora – pray and work – or a row of hearts at the entrance. Beside the window by the front of the house is a couch and spinning wheel, for anyone who wants to practice spinning yarn. A new feature of the Flett is the huge clay oven that hugs the eastern wall. The oven not only heats half the house, but also, through a row of pipes, acts as the heated bench – particularly cosy on chilly winter mornings. Connected to the Flett are the office, the kitchen, the cellar, a little meditation room, and a multifunctional living room, used for meetings, as a library, and music room (with a large selection of instruments on offer).

Also connected to the Flett is a large double room, half hallway, half foyer. In the hallway part, you can find information and leaflets about the philosophy and the various activities of the group, along with information about other similar projects. Also to be found is a weaving loom, to make fabric out the thread you have spun. Both parts of this double room are beautifully illuminated by coloured glass, sculpted into the dividing wall separating the two parts of the room, and the clay lamp shades. In the hallway is also a set of stairs that lead to the community members private quarters. In the foyer side of this room is the community shop, where you can buy things produced by the community, or by neighbours (e.g. meditation stools, honey, fabric pouches). Leading out of the foyer are two large blue wooden doors that function as the main entrance of the house. Jut beyond these doors, on one of the wooden beams, a family of swallows made their nest after returning from Africa. Unfortunately, because their return coincided with one of the driest Aprils on record, their clay nest fell apart a couple of weeks after they built it. Connected to the foyer is the art studio, in which one of the community members paints and holds art classes. The art studio is a beautiful mix of order and chaos, as you would expect from an art studio, and can hold classes of up to 10 free form painters.

Across the courtyard from the community house is the old barn. Today it function as the bike shed, a large workshop, as well as packing area for a local farmer who works in co-operation with the community. This farmer works to supply to local area with vegetable boxes in a model similar to Community Supported Agriculture. In return for allowing him to store much of the food in the barn, as well as helping with the packing of the vegetable boxes, the community gets most of the fruit and vegetables they need. Also part of this old barn, staying true to its function, is a sheep stall, where four sheep and four newborn lambs slept during the winter. Connected to the old barn by a water catchment system is another old building that is currently a construction site. Already partly renovated when the community moved in, this large building was being totally redone to add to the living space on site – thus allowing for more guests, and potentially more new members. The fourth and final building on this half hectare of village land is a house that has been built by the community about a decade ago. This building is the residence of two of the community members, a private apartment for special guests (which, because of lack of space elsewhere, included me) and a seminar room, where courses and other community events were held.

Around the buildings is a beautifully crafted garden with a huge amount of features, the most impressive of with is the large herb garden. The garden is arranged in the shape of the sun, with the centre being made up of medicinal herbs, and the rays usually planted with some kind of vegetable. Divided in four parts, each quarter of this sun is divided according to its microclimatic conditions (the hardy native plants getting least sun, the Mediterranean herbs more, etc.) and most plants have been carefully labelled, making it a great place to learn how to identify and familiarise yourself with these popular herbs. Along with this central garden are a number of smaller patches of land, scattered throughout the courtyard, dedicated to cultivation. But its not only cultivated plants that breath life into the site, there is a few space left for the wild herbs to colonise, and they were quickly coming to life in the early weeks of spring that I was there. Tall trees shadowed over the rest – ancient oaks, and a chestnut tree that was proudly bearing its huge sticky buds in spring. Keeping them company were some smaller companions, cherry and plum trees lending the world the pink hue of their spring flowers. Amongst this sea of plant life are a gang of chickens (that provided us and some of the neighbours with eggs) and a huge number and variety of songbirds (starlets, blue tits, great tits, sparrows, blackbirds, redstarts, bullfinches, wrens) painting their happy songs onto the canvas of this space.

To go with the land around the building, there is also about two hectares of farmland bout a five minute walk away. At the time of writing, there’s not much to say about it. It is mainly an empty space that has been rented out to a neighbour to grow potatoes. But in 2019 it was decided that the community should start to make use of it themselves, beginning the project of transforming this barren field into a forest garden. A forest gardening is an ecological, high yield, low maintenance form of agroforestry. The idea is to recreate the conditions of woodland ecosystems, but with mainly plants that have yields directly useful to humans; fruit and nut trees, shrubs, herbs, vines and perennial vegetables. But while some of the plants are there to provide a yield, others are there to support the yield bearing plants or create a healthy eco-systems (in a technique called ‘companion planting’). Some plants may be there to fix nitrogen in the ground, or to loosen the soil, or to attract beneficial insects. Forest gardening is probably the oldest form of human land use, but the term was first coined by Robert Hart in the 80’s. Since then the field has undergone somewhat of a renaissance, with many people now going back to the roots of agriculture, including the people of Friedenshof.

The first steps of this project are what I spent my time working one, planting trees and bushes for a hedge around the garden. This hedge will now only act as a windbreak, with three layers of bushes and trees to breaks winds both high and low, but some parts of this hedge will provide a yield, with walnut, chestnut and cherry trees among the huge variety of trees that make this hedge. Also planted were the nitrogen fixing pioneer plants, birch and alder trees, who will improve the ground for a few years before being cleared off to make room for the large canopy trees. The plans for this garden are exciting, the idea right now being to divide the garden into various sections; a section for crops, a meadow for the sheep to graze, a meadow to create high quality hay and flowers for the bees. In the centre of this will be a large lake, allowing for aquatic plants and easy irrigation. But right now this forest garden is still taking shape, and how it will evolve over the course of its construction is still up in the air. Whatever the case, I am looking forward to coming back in a few years and seeing how this forest garden takes shape.

Philosophy

What makes ‘intentional communities’ intentional is that they come together around a shared philosophy, a shared set of values. The values in most intentional communities are broadly similar (less reliant on the violence of modern society, more in harmony with nature, more autonomous) but these values are expressed in a variety of ways, with communities looking to a broad variety of different traditions for words and concepts to express their values. Once of the biggest sources of inspiration and wisdom is the Indian tradition. For well over a hundred years, the knowledge from ancient Indian has been inspiring people in Europe and all over the modern world. But, obviously, we live in a different world to that of the ancient Indian seers, and the wisdom gained must be applied to each era anew, constantly testing it upon the anvil of experience. It is by applying this ancient knowledge to one’s own life and circumstances that one keeps it alive, a living, breathing, way of experiencing reality – of navigating this complex world we find find ourselves in.

Ahimsa is at the base of essentially all traditions of the Indian sub-continent. Non-violence in thought, word, and action. A disposition of love and compassion to all beings. It is a concept that goes back to the earliest of the holy texts, the Vedas, but has been taken up by each generation anew – constantly refined in theory and practice. It is held as the highest virtue, not only in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, but, as far as I am aware, most types of religion and spirituality, the truth of its teaching being universal. In India, the reason it is so central is because of the cosmological world view. The ultimate reality is that of unity. Although the world appears to be divided in many parts, this is only because of the limited understanding of the human mind. In our confusion, we often act in a way to improve the position of the part (the single mind and body) in detriment to the whole. This is himsa (violence, or selfish action), and it is based on the cosmic ignorance of the human condition. Those who understand reality in its completeness don’t lose sight of the shared identity of all beings, and thus act from a place of love and compassion – ahimsa.

It is this ancient concept of ahimsa that Gandhi used to navigate the political struggles that he undertook. And during the course of this struggle, it became clear that practising ahimsa today does not mean the same thing as it did even a few hundred years ago. In the past it was enough to work honourably and live according to a basic code of ethics – don’t steal, don’t deceive, don’t injure others. But as Gandhi travelled around India, meeting the masses of poor who flock to see him and learning about the colonial system that had impoverished them, he realised that that was no longer enough in today’s world. Because today, although you personally may not steal from anyone, the system that you depend on has stolen the livelihoods from indigenous communities throughout the world, bringing ruin and poverty to millions upon millions. Although you may live in peace and harmony with your surroundings, the system you depend on brings violence and suffering upon the earth on an unimaginable scale. Because of our dependence on this system of violence, ‘politics encircle us today like the coil of a snake from which one cannot get out, no matter how much one tries.’ Ahimsa today must be understood in light of this social reality, this historical moment, that we find ourselves in.

The founder of the arch communities, Lanza de Vasto, was also inspired by the idea of ahimsa, and the movement still has this ideal as the heart of its philosophy today. From the French arch website; ‘The community of the arch has the goal of practising non-violence in all areas of life, be it in day to day life, work, personal relationships, political engagement, or spiritual practice. Non-violence begins with respect; respect for myself, respect for others with all their differences, respect for the earth that has been lent to us. Another word for non-violence is coherence. Coherence between my thoughts and actions; coherence between what I am, and what I believe.’ And it is this ideal, and the aim of making this ideal coherent with the whole of one’s life that leads to the next element of the community of the arch’s, and Friedenhof’s, philosophy – that of self-sufficiency. In the world that we find ourselves in, in which the system of production and consumption is based on the exploitation and destruction of human and non-human life, one must free themselves from the system in order to live coherently with the ideal of ahimsa.

By self-sufficiency it is not meant that a person as an individual has to everything by themselves. This has never been the case. We have always co-operated to survive and create meaningful lives. Freeing oneself from the system means making oneself sufficient on the community, or even the regional, level. The ethical problem most of us face today is that we are not even aware of the myriad of processes that go in to creating our day to day lives. We have no idea who makes most of the things that we use. We have no idea the environmental impact of their production. But if you provide yourself with all of the basics necessitates of life, or know the people who provide them, then you are in a position to make an ethical judgement. This is the main reason Friedenshof holds self-sufficiency as one of it’s core principles. Another reason is spiritual fulfilment, that feeling of connection with your surroundings – being part of the process of creation in which the natural world and human imagination exist in proper balance. At Friendshof this means growing crops and herbs, the spinning of thread and weaving of textiles, making cheese and dairy products, building and repairing as much as possible themselves. The level of dependency upon modern society is obviously still quite high compared to indigenous people, but lower than the average modern person. Autonomy is not a zero-sum game, it is rather a question of degree. Perhaps the most important thing is that one holds autonomy as an ideal and works everyday toward this goal.

As the principle of self-sufficiency followed from that of non-violence, so too does the principle of simplicity follow from the principle of self-sufficiency. A famous quote from Gandhi reads; ‘we must live simply so that others can simply live’. The meaning of this quote should be clear – the complexity of our lives, of our machines and gadgets, is the product of exploitation and death. The more complex our society, the higher our consumption, the more the world around us is exploited. In order to face up to the existential challenge of environmental destruction, as well as addressing the injustice of our neo-colonial system, a radical simplification of our lives is called for. Can you imagine a world in which everyone lived the lifestyles of modern Europeans, with an unending supply of consumer goods and energy at their disposal? I can’t, because there is not enough resources on earth to sustain that for one week. What gives us the right to live like this, when we know most others can’t? Why do we want to hold onto such lifestyles when we know they cause so much suffering? Do we really believe these commodities make us happy? Anyone who begins to take steps to make themselves more autonomous, to do the simple, but essential things in life for themselves, will realise this is infinitely more fulfilling than any consumer good possibly could be.

These values, non-violence, self-sufficiency, and simplicity, follow from one another. At its heart is love and compassion, from which follows the necessity to free oneself from a system of violence, which means simplifying our existence. These three elements were the core of Gandhi’s philosophy, and they are the core of the Arch, and Fridenshof’s, philosophy. But although we could describe these as a set of political values and goals, they are not only political in nature. For the people of the arch, as for Gandhi, they are the essential components of spiritual practice. The aim is organise life in a way that brings spiritual fulfilment for all, whatever spiritual path you may be on. Although the roots of the communities of the arch are in the Christian tradition (as well as the Hindu tradition because of Gandhi’s influence) any kind of spiritual practice is welcomed in Friedenshof and the arch communities (and we will look at some of the spiritual practices at Friedenshof below). But a core part of Friendshof and Gandhi’s philosophy, in contrast to the materialist progressive movements that dominated the 20th century, is they orientate themselves towards spiritual ends, rather than material ones. Obviously everyone must have their material needs met, but once you’ve reached this point, material wealth becomes a hindrance rather than a help. Contentment, love, freedom are spiritual states, not material ones. One only needs to look at our society of material abundance and spiritual deprivation for proof.

The last element of Friedenshof philosophy is not something that comes from Gandhi, because Gandhi didn’t have to worry about is, coming from a land in which community is at the centre of ones social existence. That is not the case in Europe. Over the past few centuries communities have been disrupted, destroyed, abandoned. People have been separated from each other, and now live the lives of individuals. While this may be beneficial if you want a population that is easier to control and more susceptible to consumer ideology, it is not something that is conducive to happy, secure, and loving human beings. While some are lucky enough to have a community in the form of family of friends, many are not, and often times these bonds are precarious, and not a real replacement for the permanent communities that human beings have lived in since time immemorial. But not everyone in Europe has given up on the value of community living, and many people have been hard at work in the process of community building. Friedenshof is one such community, and we can now look at some of the different elements that make up the community life.

Community Life

Between all new communities springing up, there exists a huge variety in all areas of life. Some are very focussed on ecology, others more on social relations, some are spiritual, others are more political. As well, there is huge differences in the nature of the community life that is created. Whereas some community (often the larger ones) are more like a collection of individuals who live together, others really strive to create a collective. It is in these communities that the true spirit of community can be seen. A community is not just a collection of individuals who live close together, it is itself a living organism Just as a hive of honeybees develops a consciousness of its own, above the perception of the individual bees, so too does a community of humans develop its own consciousness – taking the individual consciousness into a collective consciousness. One not only thinks about ones own well being, but also the well being of others whose destiny you share. And not only of the other individuals, but also the well being of the group itself, as a living super organising.

Like all organisms, the community has needs of its own – regular contact, clear communication, shared values and goals, a just division of work and resources. If the community’s needs are not meet, like all organisms, it will become sick and eventually cease to exist. In the modern world we are not used to living in communities any more. We are taught that the most important thing is our autonomy as individuals, and so we are often not prepared to give up on our own personal desires for the needs of the group. We no longer want the responsibilities that comes with collective living. It is for this reason that community projects often fail. Not because there is too little resources, or because there is a problem with the different community initiatives, rather because the social dynamics don’t work.

For this reason, any group that does manage to create a healthy, harmonious, community has something we can learn from. Although, like most communities, Friedenshof has gone through a number of interpersonal crises, it has survived and thrived for almost thirty year, and today it is a well functioning community that continues to grow. We can look at some of the factors of their success, the first of which being the clearly defined set of shared values. The ‘Rule of Friendshof’ was written in the early 90’s before the project began, and is continually reflected upon, and sometimes changed when the group decides it is appropriate. Rather than a set of strict rules, the Rule is a set of guiding principles that each person decide how to to apply for themselves. Within the rule is a set of values and intentions relating to, for example; relations with each other, relations with the self, with guests, with spirituality. There are values defined in regards to the economic existence of the community, its relation to the wider world, and well as their own place of abode. Having a set of clearly defined values and intention creates a clear direction and common cause, something that helps to guide action and avoid conflict and confusion.

After a set of shared values, one of the most important elements is the shared daily routine. This starts 7:30 with an (optional) morning meditation for 20 minutes. Next is the Morgenbegrüßung (morning greeting). Taking place in the garden (if its nice out), or in the foyer (if it’s not) the whole community would sing a song, dance a dance, hear a short text that is chosen at the start of each week, greet everyone individually, and share with the others what they are doing with the day (and if they need any help). This makes sure people connect early in the morning, sharing some nice vibrations before starting out with the day’s labour. Work would last until 12:15, and at 12:30 there is another 20 minutes optional meditation sitting. At 13:00 we would meet up, sing a song, and the person who had cooked (being a different person each day) would present the food to everyone. After sharing lunch around the large table in the Flett or outside in the garden there was a break in the afternoon.

Eventually, people would go back to work for a time that is left up to your own choosing, but was generally from around 3 to 6. Throughout the day, usually on the hour interval, there was a ring of the bell signaling a Rapelle, a chance for everyone to stop what the are doing for a minute and concentrate inward – become aware of the breath, the body, the inner stillness. The final meeting of the day would be at 7 for the Gebet ums Feuer (fire prayer). A fire is lit under the stars, the Gebet is recited, a final song was sung, and everyone wished each other a pleasant evening and a good night. So as you can see, the daily programme is fairly full. This not only ensures that the community regularly comes together, but also creates a regular and shared rhythm by which one can structure their day, and their week.

Along with the daily routine, there are also a few weekly events. There’s the Hausrunde (house meeting) and shared cleaning of the house on Monday, and a few hours of shared work on Tuesday (where the whole community comes together to work on a larger task, or tasks). On Friday there is always a simple meal of potatoes and spelt wheat, in which the first 15 minutes are eaten in silence, in a ceremony to encourage a mindful relationship with one’s food. Also Friday is the Redestabrunde, a circle talk in which we talked about how we were doing that week. At two week intervals, there was also is the ‘retreat’ for the permanent members of the community – where they meet to check in with each other, etc. Finally there are the bi-annual day long mediation sessions, in which someone from outside comes to act as a mediator for the group – for the community to go over anything that might be more difficult to address in the regular meetings.

While all this may seem like a lot to people who don’t live in communities, it ensures the proper running of a healthy community. This ends up saving a lot of time in the grand scheme of things. Instead of having to earn everything yourself, or do all the work of a household alone, you share your work and income with other people, meaning you have to work a lot less on this stuff. This is another important part of a community – a shared economy based on solidarity. The money that the community makes through workshops or commerce, as well as income of the individual community members, flows into the community saving. From these savings they buy food, pay rent, bills, transport costs. Money from this pot can then also spent on luxury goods and services. Those who don’t have a source of income can contribute in other ways. The idea of a solidarity based economy is not to be fixated on money as the only form of value, instead creating a culture of give and take based on needs and capabilities. A functioning solidarity based economy is a sound basis for love and mutual support in a community.

And because each individual must work less to maintain the household, they have more time to spend what they are truly passionate about. At Friendshof this ranges from yoga, aikido, meditation, Zen painting, or the dance of universal peace; to carpentry, clothes making, herbalism, bee keeping, and cheese making. Often these are offered as workshops to other members of the community or people from the wider area, building links with the local region. So far from the individual being lost in the maze community structures, the community allows for greater individual self-realisation. Along with lightening the general work load, community enables self-realisation by being a source of inspiration and encouragement.

And as well the community allowing for the personal development of the individual, it allows for a greater connection and solidarity with the wider world. This connection takes place through a number of platforms. On the national level, there is a group of about a dozen people all across Germany who, although not living in a community house, live according to the ideals of the Arch movement. Along with living according to a set of shared ideal, the German Arch network meet semi-regularly meet at Friedenshof for exchange, support and inspiration. Along with the national Arch network, there is also the international network. Across Europe there are four other community houses, as well as Arch members all over the world (or at least all over Europe and Latin America); Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Ecuador ,Belgium, Spain, Italy, France and Switzerland. The biggest Arch meeting at Friedenshof takes place on the Summer solstice, where all the communities come together to celebrate. Finally, there are links to wider community movement in Europe and the world over, with Friedenshof members often being at the GEN Europe meetings as a representative of the Arch movement.

Fin

The Community of the Arch is perhaps the earliest example of the modern community movement, beginning decades before the first eco-villages were founded, and even long before the hippies began experimenting with new ways of living. That the model is still alive today is proof of the long lasting potential of the community movement. Based on a principle of non-violence, as well as a life of community, spirituality and simplicity, Friedenhofs has been steadily working toward the goal bringing a little bit more peace to the world for the last 30 years. Long may it continue.

For more information: http://www.friedenshof.org/

1 reply on “Friedenshof”

Hallo, Dara. Ich habe eben deinen langen Bericht mit den vielen Gedanken und Reflektionen gelesen. Danke auch für die tollen Fotos. Ich fand alles sehr spannend und mit viel wichtigen Hintergrundinformationen. Ich hoffe, Du hast gutes Feedback bekommen. Lass es Dir weiter gut gehen. LIEBE GRÜßE BÄRBEL