*note: This is an excerpt from a larger work that will be releases at a future date. For this reason, I have not included a deeper diver into the Zapatista experience here. For those who would like to learn more about the Zapatistas, see bibliography below*

Introduction

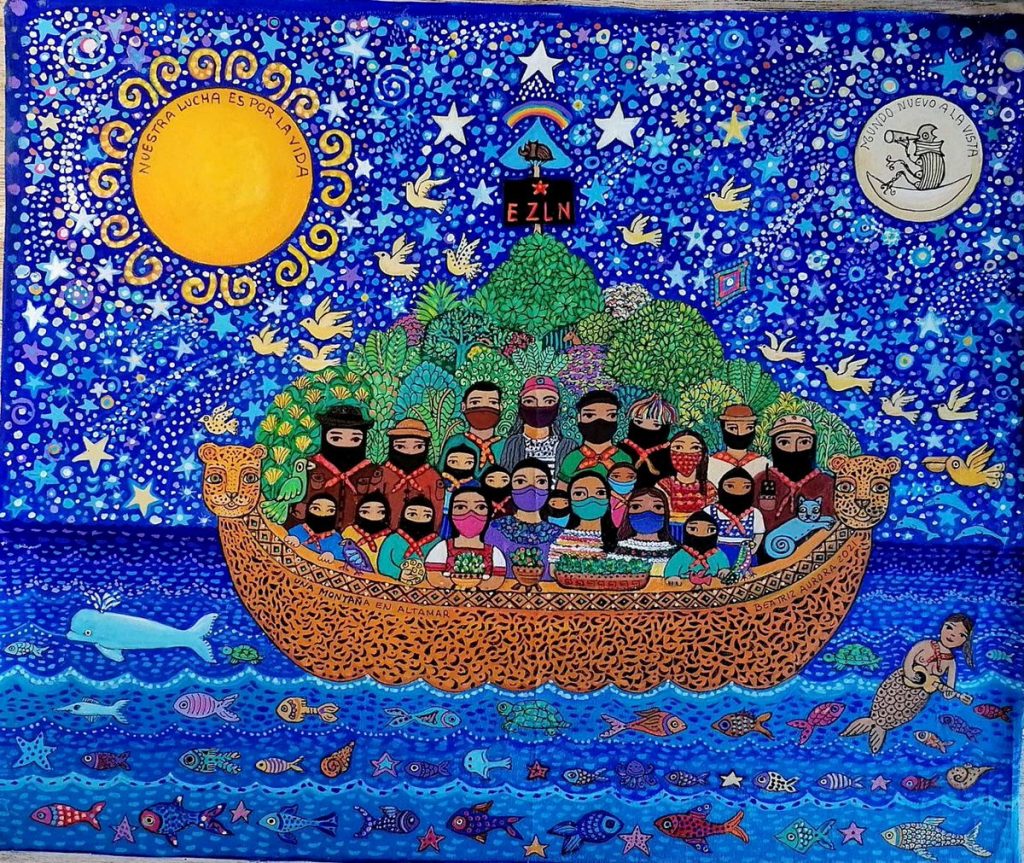

In 1994 thousands of indigenous mainly Mayan communities staged an armed uprising to remove the Mexican government from a large territory in the jungles and mountains of the southern state of Chiapas. Upon doing so they established an autonomous territory within which they could govern themselves. However, the Zapatistas have no intention of setting up their own Mayan nation state. To them, the state itself is a form of domination; government from above, in which a special class of politician impose government on everyone else. What they decided to do instead, and what they have spent the last 30 years doing, was to develop an autonomous form of government without a State, based on democratic decision making from below.

In the first place, this meant greatly decentralised political power, giving every community much more autonomy over their own affairs. However, the Zapatistas also saw the benefits of large scale institutions of government. They cover a huge extension of territory and many tens of thousands of people. Combining those forces would be big advantages in constructing their autonomy and resistance. Their challenge was therefore to create a large scale government without it turning into another form of government from above; one in which the people command and the government obeys. This form of government is one which is still in progress, and will always be in progress, as one of the guiding principles is that people constantly adapt their government to changing internal and external conditions, but we can briefly mention some of the mechanisms developed by the Zapatistas to ensure that their government retains a genuinely democratic character.

The Zapatistas have three levels of government; community, municipality, and regional (the Junta de Buen Gobierno). The communities are organised by democratic assemble, and the municipal and regional governments are co-ordinated by delegates. The role of the delegate is merely to convey the will of the community, as expressed in the community assemblies, but with the delegation of power comes the risk of the abuse of power typical of state politicians. To prevent this from happening, the Zapatistas have developed a series of mechanism to keep their delegates in check. One such mechanism, central to any truly democratic system of government, is the ability to recall their delegates at any time if they are not properly serving their communities. To ensure that delegates remain firmly embedded in their communities, serving delegates spend half of their time in the communities, living their normal life, and the other half fulfilling their governmental responsibilities. There is no financial rewards for being a delegate, and turn as ‘governor’ is instead seen as a service to the community. Finally, there is a regular change of government, preventing anyone from staying too long in a governmental role, with the idea that eventually everyone gets a turn as delegate. These mechanism ensure that there is never any separation between the governors and the governed, and this, combined with the decentralisation of decision making power, has created a large scale structure of political co-operation, without the need of a centralising, hierarchical, and bureaucratic state.

Another element of the Zapatistas anti-state posture arises from their own dealings with the Mexican state. Since the Zapatistas established their autonomous government, the Mexican state have done everything in their power to crush them. First with the regular army, then with paramilitaries, and then with a ‘low intensity war’, in which they incentivise different groups to attack them. In the beginning the Zapatistas tried to negotiated with the state. They signed the San Andrés Agreement, which was meant to amend the constitution to allow indigenous communities in Mexico to organise themselves autonomously. But despite signing the agreement, the state went back on their word. They continued their military campaign against the Zapatistas, and never implemented the promised constitutional reforms.

After this betrayal, the Zapatistas decided that the Mexican government couldn’t be trusted to negotiate anything in good faith. They stopped trying to find any arrangement with the state, and instead went about constructing something that was completely autonomous. As well as their autonomous forms of government, they also organise their own schools, hospitals, and co-operative economy; all with very scant resources. Their position on the state is clear; it is an oppressive form of organisation, it cannot be trusted, no co-operation is possible. One of the basic requirements of being part of the movement is that you do not co-operation with, or accept any form of financial assistance from, the Mexican state.

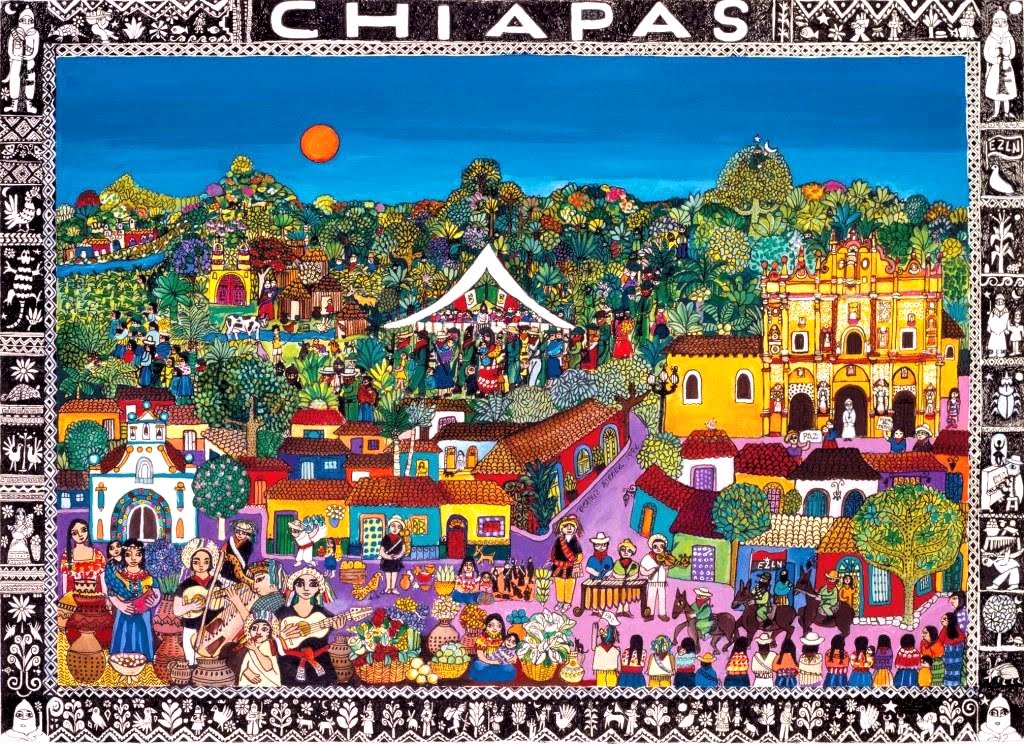

The Zapatista movement is composed of thousands of villages and many tens of thousands of people. As well as spreading out across very different geographical region, with some communities up in the high temperate mountains, and others in dense jungles, the Zapatista movements also brings together a number of different cultures; tzotiles, tzeltals, chols, tojolabales, and zoques. While the underlying Zapatista philosophy and organisational structure unifies all of these groups, every community has also had their own unique experience of the resistance and autonomy.

Nuevo San Gregorio

Nuevo San Gregorio in the region of Luciano Cabanas, in the territory of Caracol 10, is one of these communities. From 2019 until the time of writing (early 2022) the companeros of this village have been suffering from an invasion of their lands. At the end 2021 I stayed for two weeks in this community as a human rights observer and bore witness to their resistance, a form of resistance that might surprise people whose main knowledge of the Zapatistas is their armed revolt of 1994.

Nuevo San Gregorio is located about one hour from San Cristobal de las Casas, in the municipality of Huixtan, in the temperate mountains of central Chiapas. It is a small village composed of six families in a beautiful valley surrounded on all sides by mountains protected by forests of pine and oak. Before the invasion of their lands (which we will get to shortly), the territory consisted of about 180 hectares – some it sloped forest, some of it valley plains for pasture, some of it arable land for planting corn and other crops. This land obviously produced a lot more than was needed by six families, and so most of the surplus produce went to the Junta de Buen Gobierno to divide amongst the communities in need.

Before the Zapatista rebellion of 1994, the land was the property of a single finquero, but after the land was recuperated, it was put in the hands of the people who had been working it. The community has two main places of residence, one below the centre, close to the secondary school, as well as the dilapidated house of the finquero. The other higher up on the mountain. In the centre of the village, is the casa de salud, the primary school, the church, the village shop, as well as a number of spaces that were built for the new collectivos that were created after the invasion.

Over the years different companeros came and went, some leaving the land and the organisations (including some of the future invaders), others joining later on. One example is of Moises (not real name) who joined the community after his village, which was previously communally managed, had been privatised and divided up by people looking to get government subsidies. After this parcelling up of the village, Moises was left empty handed, having previously worked on the communal ejido. So he started going to a autonomous school, open to all, and began learning, among other things, to read and write and Spanish. He was then asked if wanted to join the organisation and become part of the community, to which he happily agreed and joined with the rest of his family in 2005. He continued with the autonomous education and went on to become a promotor de educacion. Another example is of someone who joined the community when they were just nine years old. His father died when he was young because of alcohol, and his mother wasn’t able to look after him properly. He heard of the Zapatista movement and resolved to become a part, coming to Nuevo San Greogrio when he was just nine years old. Now he has a wife and two children, and is very active in many of the wider Zapatista organisation.

Village life was interrupted in 2019 when a group of neighbours, one of them with a brother in the community and several others being cousins, arrived and began fencing off the community lands. They threaten violence and posted guards with machetes outside the residential areas and the centre of the village to monitor everyone. They began cutting down trees and turning them into post to make barbed wired fences around the areas they were now claiming for themselves, which was essentially all of the land. From the 180 hectares, the community was left with about 10 hectares for their places of residence, communal spaces and land to farm and pasture. These invaders were ex-zapatistas, who decided they still had a legitimate claim to the land despite leaving the organisation, and other important members of the wider community, such as an ex-policeman and a commercial logger.

Five hundred years previously the Spanish arrived to appropriate land and resources, only for this land to be recuperated in 1994 by a group of indigenous people who put the fruits of the land back in the hands of the people who work it. But the logic of greed and self aggrandisement took firm root. Many of the invaders already have large ranches and so can`t work the land by themselves, instead paying labourers to work the land for them.

Some of the occupied lands are surrounding one of the residential areas of the village. This severely restricted the movements of people of these houses, as well as the secondary school, forcing to the village to close the school for the safety of the students and teachers.

Initially the Zapatista villagers tried to start a dialogue with the invaders, under the moderation of the Junta de Buen Gobierno. They wanted to come to an agreement with the invaders, offering them a part of the land for them to work, even offering half of the total land in order to try and reach some kind of peaceful arrangement, but the invaders weren’t interested in the deal. It seemed as if they wouldn’t be satisfied until they had everything and the people of Nuevo San Gregorio have nothing. Greed knows no limits, and capitalist rewards for dispossession and exploitation are vast. Eventually the talks were broken off because of the outbreak of the pandemic and the suspension of activity by the Junta. With the end of the dialogue, both parties agreed not to enter the lands until the dialogue could be resumed and a deal reached. Two days later the invaders were back occupying the space, and working the land.

Rather than meeting these threats and provocations in kind, the community of Nuevo San Gregorio didn’t respond with violence. But neither would they give in and abandon their homes, as the invaders were hoping. If they weren’t able to work their land, they would need to find a new way of surviving, a new type of resistance, so they opened up various co-operatives and began developing different crafts. The men began working with wood, making cups, sugar holders, furniture, etc. The women began with the work of embroidery and pottery. They built a few workshops, acquired a few basic tools, and got to work. Nobody was an expert in anything to begin with, but the knowledge that they did have, they shared amongst themselves. Now, a little over one after starting, they were creating very beautiful works which they were selling in the shop of Zapatista supporters in San Cristobal. Along with these new co-operative were the acquisition of chickens, as well as planting a lot of fruit trees in the lands that were left to them.

In the time that I was in Nuevo San Gregorio, the invaders would constantly come by to work the milpa, take care of their animals which are grazing in the occupied lands, chop down trees, or reinforce posts. But one event was particularly impactful for the community, which was the plowing of the communal pasture. This was the last significant piece of land that the invaders hadn’t occupied, and the last piece of land that provided their 22 cows and bulls with grass. A few days before my arrival, the invaders arrived to block the water canal that was going through the land to dry it out to prepare it for the plow. A few days later, we got word that two tractors had arrived in the next village over. So by the time they arrived, we were aware of what was to come. The next day we woke up to see that 30 men had gathered at the house of the old finquero with the tractors and were preparing to move. Next we saw men with machetes take up various positions around the village, the closest one to us was no more that 5m away from the centre of the village.

As the men began entering the occupied land toward the pasture, a car began patrolling the street between the various guards. We were told a man, who was considered one of the leaders of the invasion, was carrying a pistol. As we didn’t have a view of the pasture from where we were in the village, all we could do was sit and wait. As the guards were posted at every corner of the settlement it was impossible to move anywhere. The people of NSG told me that it felt like they were being kidnapped in their own homes. During this invasion, a police car rolled up and had a friendly chat with one of the of guards., who turned out to be his son. This went on for two and a half days before they left and the compañeros could go and take a look at what had happened. The whole pasture had been plowed aside from one little corner that was too muddy for them to plow. The animals, some already pretty skinny, wandering around their destroyed pasture was a sad sight. The economic blow to the compañeros was huge. Often these animals served kind of like savings for the community, to be sold in case they needed to pay something like emergency medical bills. These animals were the last of the valuable resources that the compañeros had left, but also they felt sorry for these living beings. They told me; ‘these animal are also our compas, they have also been resisting the invasion these last two years, and now they are going to suffer hunger.’

In a situation like this, it would have been easy to have fallen in a spiral of violence. But violence only begets violence, and afterward it becomes difficult to pull oneself out of the abyss. The other option would have been to sell their cows and move to a place where violent invasion of their homes isn’t a daily reality. But they have gone down neither of those roads. Perhaps the reason for this is that these compañeros y compañeras aren’t just in resistance for themselves, nor only for their kids. They are also resisting for the nature, who will suffer greatly if left to the mercy of the invaders, who would sell all the trees in the forest until there is nothing left, as well as begin employing methods of industrial agriculture as soon as the natural fertility has been exhausted. They are resisting for all the people who died in 1994 to give them this chance to live an autonomous life, as well as all those who will come after them and deserve the same opportunity. They are resisting for other Zapatista communities, and communities in resistance all around the world, that they may take strength and inspiration from their struggle. In contrast, the invaders are motivated purely by self interest. If they did manage to successfully claim the land for themselves, they would likely start a conflict with each other to not have the share the land with each other. Groups held together by bonds of greed rather than solidarity quickly fall apart, and one hopes that this happens sooner rather than later for the sake of the Nuevo-san-gregorians.

In many ways this form of resistance is very similar to that of Mohatma Gandhi, who named his type of resistance ‘satyagraha’ – truth force. By confronting aggression head on, not with violent retribution, but with patience and perseverance, not giving in to oppression, but just as equally not giving into anger and hate, the power of truth could be manifested in many ways. Gandhi believed that all human beings have the capacity to act ethically, that inside everyone is an innate sense of justice, and that through the power of truth, this ethical sense of justice, could be awaken. An important part of the resistance of Nuevo San Gregorio is the documentation and wider propagation of what was happening to them. In the weeks that I was there, details of the invasion were only just beginning to reach regional and national newspapers, as well as public denouncement from the Junta de Buen Gobierno and local human rights organisations. Who knows what effect will making these crimes visible have here. And if the invaders sense of compassion isn’t awakened, perhaps their sense of shame will. OR the sense of indignation of the rest of the people in the wider community. Truth is a powerful force, capable of raising armies and toppling tyrants, capable of provoking powerful feelings of shame, compassion and injustice. And through its propagation we have the power to change the world around us. While it may be difficult to imagine these invaders freely giving up on their attempt to appropriate the land, it would have also been difficult to imagine the British giving up their most lucrative of colonies because of a serious of peaceful protests.

The resistance, said one of the members of community, is what gives them the strength to continue in the struggle, and to stay positive and optimistic. Aside from two understandably tense days, the rest of the time, the Sangregorianos were in a positive mood, working on their various crafts, sharing hopes (as well as fears) by the fire, playing a lot of music (marimba, guitar, base, singing, and drum set) as well as celebrating the Guadalupana on the 12th of December. They maintained that there were also positives to be taken from the invasion. They opened new co-operatives and began developing new skills. They welcomed people from all over the world to their community as human rights observers, and could inspire them to bring the spirit of resistance back to their own countries. I was personally very inspired by their resistance.

I was quite surprised to see the level of commitment to finding non-violent solutions to this violent invasion. As I was told – ‘Even though they come to invade our lands, posting armed guards to surveil us, and making threats, we refuse to be provoked. If this had happened to another community there would have been a massacre by now, they would have gone down with guns and had a shoot out, but that’s not our way, that’s not what we are about. We are struggling on behalf of life, not of death’. This made me realise the sincerity of the statement made in the 90’s ‘we are soldiers so that nobody has to be a solider’, as well as the profundity of the transformation that has taken place since ‘94, from a militia to a civilian movement.

But, although there is no doubt that the compas were doing their best to resist the provocation and stay positive, this must be becoming more and more difficult with each passing invasion. Having to sit and watch as people come and work your land, threaten, and provoke you, naturally evokes strong feeling of injustice, and the will to do something, take some action.

One idea was perhaps to experiment with non-violent forms of disruption, such as gather a few hundred people, and block the path of the tractors when they arrive to plow your fields. This would have certainly affected the invaders, who had to pay quite a lot of money to hire the tractors from a village almost a day away. However, in the first place, the community was told by the Junta de Bien Gobierno not to make any moves until they had reconvened after the pandemic had subsided. Secondly, even this non-violent disruption could provoke further violence from the invaders, and there are important reasons for the strict use of a completely non-provocative strategy. These six families all live there with their children. They have nowhere else to go. Although it was very frustrating to sit and watch these invaders come and work their land, any kind of direct confrontation would likely be the next step down a path leading to the death of members of their family. Violent conflicts over land are very common occurrence in Chiapas. Another conflict happening at the time of writing is happening in the Zapatista community Moises Gandhi. In many ways it is quite a similar situation, ex-Zapatistas (a group now known as ORCAO) who left the organisation but then decided that they had a claim to the land recuperated by the Zapatistas. But in Moises Gandhi the situation quickly escalated, and now the people from Moises Gandhi suffer under almost daily gunfire, kidnapping and their buildings being lit on fire. One of the invadors of Nuevo San Gregorio is apparently related to members of the ORCAO, and the spectre of the violence being suffered in Moises Gandhi is hanging in the air in the community.

Bibliography:

https://radiozapatista.org/?page_id=20465