Tucked away in one corner of Moritzplatz in the heart of Kreuzberg is the urban garden and cultural space Prinzessinnengärten. Behind tall fences of reused wood, intertwined with plants, one could easily walk by without realising that something special lies behind. But upon entering one feels instantly invited by the variety of plants and self made constructions found in the allotment. The perfume of velvety herbal leaves draws you in, the splendour of flowers in bloom brings you to a pause. Along with a huge variety of herbs and vegetable plants growing alongside every path, there is a large amount of young trees growing in the allotment, providing welcome shade from the sometimes sweltering Berlin summer sun, while also storing the little warmth that can be wrung from the colder months.

The garden is full of things to discover, little nooks and crannies often hidden by plants or constructions. At the heart of the garden a place to sit, eat and drink. For those who want to try some of what’s cultivated on site, there are containers turned into café and food stalls. In front of this is a small wooden shack with some books for people to sit and read. Behind that is a wooden passageway in which market stalls are set up. Here people can cook, play table tennis, or whatever else takes their fancy. To one corner there is an apiary and the hum of busy bees collecting the sweet nectar from all the plants in their surroundings. Beside it is an open area without any trees, filled with potted plants, taking full advantage of the suns rays falling upon the earth. By the entrance is a huge, three story modular wooden structure, dubbed die Laube, which is a fairly new addition to the garden. Die Laube functions as an event space, a place for people to sit and relax, looking out over the garden from up high, or admire the form of this impressive structure from below, invaded by plants growing in, around, and through it. The most impressive feature of structure is its huge copper heart that sits to one side of it. This sculpture, made from welded copper plates in East German in the 80’s, beats once a day at six o clock.

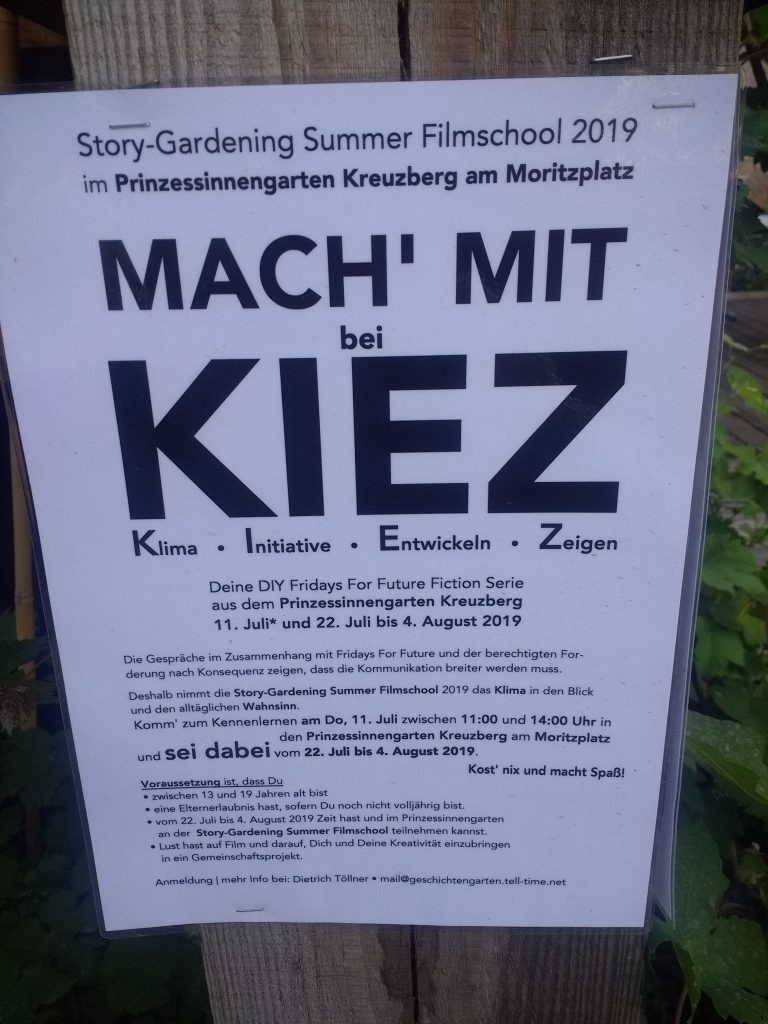

Every second Sunday the place is abuzz with a flea market, with dozens of peopling coming and setting up stalls giving you the chance to buy home made soaps, second hand clothes (often ‘zum Gescheck’ – for free), or old trinkets. Aside from the flea market, the space is used as a cultural space for many groups in the city. The day I arrived for the plenum, which I will recount in a moment, there was a group of around thirty youth, all about to dig into some food they had just finished cooking. One of the organisers of this group told me that this was a sustainability camp, where young people from all over the world would come and learn about sustainable technologies and ways of living. These youth would, over the course of a week or two, develop ideas and designs which they would then go onto construct themselves. The week before, upon entering the garden, I heard the unmistakable sound of the berimbau, a single stringed musical bow often played as an accompaniment to the Brazilian martial art/dance of capoeira. Sure enough, there was a group of people toing and froing, jumping, spinning, and swinging in the forms of the martial dance.

At the time of writing, the garden is operated by two organisations (or Vereine). One Common Ground, who built the three story structure, the other, Nomadisch Grün who run the café and food containers. This situation was about to change however and, at the end of 2019, it will most likely be run solely by Common Ground, or rather a new group that will emerge from Common Ground. The reason for this I learned at one of the Common Grounds Monday plenums. These organisational meeting are open to anyone who wants to take part and get involved in the garden. On the day I showed up all the people were very inviting and seemed happy about about a new face. The meeting takes place on some part of the die Laube, everyone sits in a circle, one person takes minutes, with the circle is open for anyone to interject or make proposals for topics.

Upon listening to other people in the circle for a few minutes it was clear that there was one topic which was hanging over the rest. Neither Common Ground, nor Nomadisch Grün had ownership of the land and were operating on the basis of a temporary contract. This contract is finishing up at the end of the year, and like many parts of Berlin, this previously run down plot of land that was brought to life by the inspiration and dedication of the people, is now worth a lot of money (in large part because of those people) and commercial forces are moving in to capitalise on the land. Nomadisch Grün have decided to accept this turn of events and move to a different location. Common Ground have decided to resist turning another piece of this green earth into concrete, and want to stay long term. But despite this intention, the air is clearly thick with uncertainty. Uncertainty for what the garden will be in the future, uncertainty as to who will be responsible for it, uncertainty as to whether there will even be a garden come the end of the year.

One thing that was certain in plenum however was that there will be a clear change from the garden that exists at the moment of writing. At the very least, half of the project will up and relocate to another part of the city, so there will be a lot of room for new growth new ideas. At the end of the plenum, they decided to collect questions for an important meeting that was going to take place the following month. In this meeting, the fundamental questions of the project would be discussed. Who are we? What do we want to achieve? Are we a garden space or a cultural space? How would we want this garden to look in ten, twenty, thirty years? Which other groups do we allow use the space? A theatre troupe wants to build something here. This theatre troupe need to support themselves and charge an entry. Does that not close the space to others? Who can even answer these questions? It was a exciting encounter with genuinely open and democratic understanding of how to shape the space around us, but what was sad was that everyone was aware that there was a good chance that these questions would find no outlet in action, and instead be overridden by the grey concrete logic of profit maximisation.

A few days later I arrived back in the garden and saw a friendly face from the plenum engaged in enthusiastic conversation with two people in their 20’s. These were two friends, one studying architecture, the other a recently qualified carpenter. After talking to one of them for a minute, I realised that I had heard of them in the plenum. They planned to build an information kiosk by the entrance. Both were amazed that a space like this existed, ‘I passed by it many times on the bike but I never knew this place existed’ said the carpenter (perhaps one disadvantage of having the surrounding fences overflowing with plants). ‘You mean anyone can just come and use the space to do their own projects? Wow, in five years I’m gonna come here and set up a workshop, and teach people how to build tiny houses, earthships and this’ gesturing toward the Laube, and positively beaming at the prospect.

Afterwards, talking to the person from the plenum, I asked how he thought things were turn out? If he thought there would still be a project in 5 years for this carpenter to come and teach people how to build tiny houses? ‘The problem is that everybody wants to come and do their project, but nobody wants to think about the amount of work that goes into having a place like this. Who is going to go through the struggle to keep this a community space? Who is going to organise and take responsibility for this space? People want to come and set up their hydroponic tea plants but nobody wants to be Hausmeister (caretaker). The council certainly don’t. They just want to rent it out to a business and not have it as another thing to worry about. The neighbours aren’t interested, most of the people you see in here are tourists. People come up and say “wow what an amazing project”, and I think “great” and say “would you be interested in getting involved?” and the response is almost always, “ah I’m only here for a holiday”’.

We can speculate as the causes of this problem, the lack of engagement from the local community. One reason could be, as was the case of the carpenter, lack of visibility. That people simply don’t know that a place like this exists. Another is that Kreuzberg is the heart of gentrification in Berlin. Even 15 years ago Kreuzberg was filled with, predominately Turkish, communities of people who thought that they would live there their whole lives. However, high rent prices have driven many of these communities out, to be replaced by luxury apartment to rent on short term leases to the the global nomadic elite (not known for long term community engagement). Another may be that the concept of a open cultural space in which people can come and learn, teach and explore new ideas has become alien to people, used to their free time being organised around commercial places of consumption.

But there was a glimmer of hope in terms of engaging the local neighbours. was a recently started project of collecting all of the organic waste from neighbours. If Prinzessinnengärten is to continue, one thing that everyone seemed to agree on that it should be a real ecosystem with ground soil rather than potted plants. Along with the new compost toilet, there is a new initiative to collect material for new soil by neighbours coming and bring their green waste. One of the people at the plenum happily reported that this project was bringing in lots of people from the neighbourhood, happy to come with their old straps to contribute to the grow of the garden. Perhaps these little actions will lead the kind of engagement that will allow the garden to survive long term. And as one voice in the plenum said – ‘At the end of the year [when Nomadisch Grün move location] this garden will be largely empty. Hopefully then the neighbours will finally say to themselves “oh this place will be gone unless we do something about it”’.

The trend of abandoning the countryside to heavy machinery, of turning nature in a factory to feed the bloated cities, cannot continue. Building a harmonious relationship with nature requires a human touch. The industrialisation of agricultural has meant that human labour has been replaced, machines that exhaust the soil, poisons and chemical fertilizer but this can’t continue for very long. For the sake of healthy ecosystems and healthy human beings a new agricultural revolution is called for, based on a type of agricultural that is being developed with methods such as permaculture or afro-forestry. What’s more, huge urban areas of millions of people requires such a huge complex of heavy industry for its creation and maintenance that this type of settlement is not sustainable. Having said all this, people have long lived in cities, and cities that can be supported by their immediate hinterland can find an equilibrium with their surroundings. But living happy lives in the midst of an urban jungle requires a rethink of the way we have organised space up till now. We cannot forfeit every patch of green to logic of capital. Along with a healthy urban ecosystem, public space must be the priority. The city should be full of places where people can go and learn, create, share, explore, or simply exist without having to spend money. And so spaces like Prinzessin Garten can act as a model for spaces in an democratically run city, orientated to toward the prosperity of life, and not the maximisation of profit.