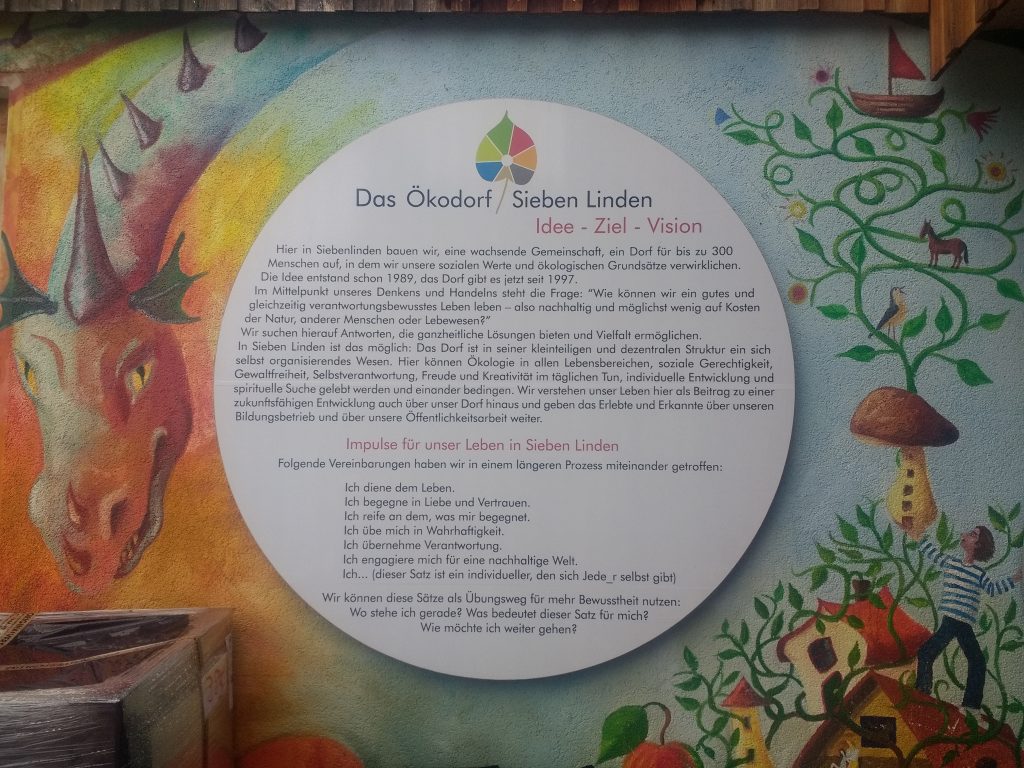

Formed in the 1997 around an old farmhouse on the border territory of the recently disbanded GDR, Sieben Linden is today one of the best known eco-villages in Germany. And not without reason. Over the past 25 years its members have been hard at work in the fields, turning sterile industrialised acreage into regenerated farm land; hard at work in the forests, transforming lifeless pine plantations into a diverse forest; and hard at work in the home, creating a community culture from the many individuals that have come together in pursuit of a shared vision. Finally, and probably the biggest factor in explaining the fame of Sieben Linden, is the wide variety of eco-buildings, constructed according to the principles of natural building. In particular, the straw bail houses are widely renowned, and Sieben Linden was for a while home to the largest straw bail house in Europe. Today Sieben Linden is a community of 150 people, with the potential to one day house 300.

Space, Projects & Community Structure

After a train and a bus ride from Wolfsburg, the closest city, I find myself about a ten minute walk away from Sieben Linden. Because of the capricious nature of hitch-hiking, I arrived late at night. All was quiet, and I was a little unsure of where to go. At the entrance was a map of the village, so took a guess at what was the main building, and made my way over. Luckily, another guest was still up. He showed me to my room where I could get a bit of much needed sleep. The next day we had a small tour of the place but, considering its size, we couldn’t see everything.

The grounds are huge, one hundred hectares if not more. Most of that is forest but there is also huge space dedicated to gardening, outdoor recreation, communal areas, workshops, a school, and residences. There are two forms of living space in Sieben Linden; Bauwägen (trailers) and communal houses. I’m not sure the exact numbers but it seemed like a fairly even spread between the two modes of living. The fact that Sieben Linden has these two options means that people can live here comfortably, even if they don’t want their day to day to be fully integrated with community. The Bauwägen are good option for those who like to live more alone, and have their own space when they want a retreat from community life. Those living in houses have a more social existence. Many of the houses represent a community within the community, and people choose to live together based around some common ideal or purpose. Maybe that ideal is a political orientation, or a shared understanding for how to live. For example, one house, called the Heilhaus (healing house) is where the healers of the community live, a doctor, masseur, yoga practitioner. One exception to this is the Strohpolis, once the largest straw bail construction in Europe, which is more like an apartment complex than a WG.

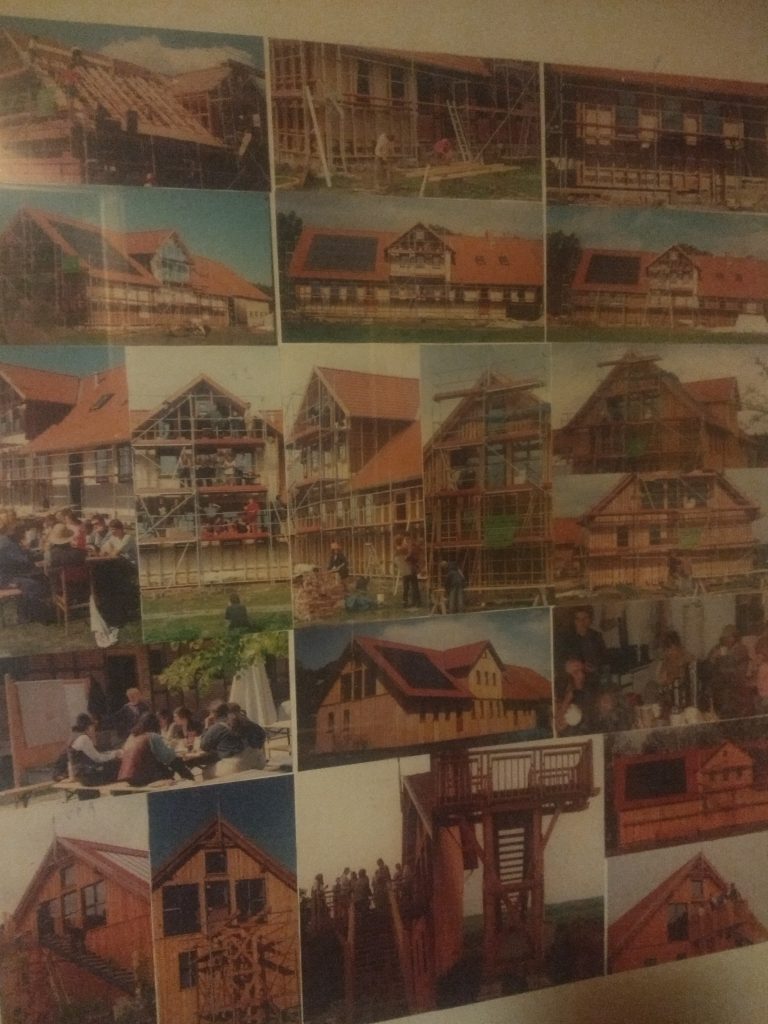

In all, there are eleven houses, all of which have all been built according to the principles and methods of natural building. Natural building is a way of building focused on sustainability. Some features of natural building design; using locally sourced, minimally processed, renewable, plentiful, or recycled materials materials; working with the surroundings to ensure the building will not need a high energy input; reliance on human, rather than machine labour; providing a healthy environment for the people and nature that will live there. In Sieben Linden, most of the houses are built using straw bales plastered with cob (a mix of clay, sand, and straw), and wood from the forest beside the community. Most of the energy needs are met by solar panels on the roof, and the heating is done with a huge wood burning stove, through an integrated system of pipes, efficiently heats all buildings. All the toilets on site are compost toilets, and the water comes mainly from their own well and water catchment system (although they were forced to connect with the government water circuit in 2013). Water waste is cleaning by plants in the waste water system.

Aside from the residences, there are a number of other buildings. The only building that existed on site when Sieben Lindeners acquired it was an old farm house, nicknamed the ‘Bunker’. Today this is the community building. It is split in two on a right angle and fulfils a number of community functions. On the side you have the Regiohaus. This end of the building has offices for the administration, die kneipe (the pub) and dance hall for community events (such as dancing, film nights, talks, etc.), the Schmuck Laden (jewellery shop) which also functions as a workshop, and Naturware Laden, a food co-op and organic shop for the residents and guests. In other arm of the building, the Sonneneck, is the space where most guest stay, with a number of guest rooms and two seminar rooms. As is common in many eco-villages, the majority of their income is generated by courses and seminars. Throughout the year there is a full calender of courses on a huge variety of things; perma-culture, straw buildings, Chinese dancing, non-violent communication, etc. Also in the Sonneneck is a library, community food store and kitchen.Aside from of the main house, some of the other built features are the sauna, the Haus der Stille (House of Stillness), the free shop, the Platz der Ahnen (Ancestor Place), and the Globo, a beautiful outdoor space created from willow weaving, with firepits and a clay pizza oven.

Aside from all the building, there is also a lot of work going on outside. There are huge gardens to provide the community with food (apparently they are about 70% food self sufficient), which are all run according to the principles of organic gardening or permaculture, and from next year onward, using methods of agroforestry. Also on site is a huge orchid, quite famous in horticultural circles for its huge selection of apples, and when I was their there an exhibition of some the different varieties on display in the info pavilion. Surrounding Sieben Linden were mono-cultural pine forests, eerily planted in the straight lines that make them easy to manage. 75 hectares this forest now belongs to Sieben Linden, and they are undertaking the challenge of turning them back into more natural forests. Also on site were two ponds – one clean, where people can swim in the hot summer months, one not clean but beautiful, surrounded by ancient oaks and the misty mystic energy of late autumn. The animals kept on site are horses and lamas. The horses help with moving heavier stuff and I’m not sure to what end they keep the lamas. The last thing to mention about the site itself is one section is dedicated to the Waldkindergarten (Forest Kindergarten), which has about 20 kids.

Along with the buildings and natural structures that have been built over the last twenty years, a number of community structures have also been developed. On the legal end of things, members are organised into various Vereine depending on which part of the community they are involved in. The main organisational structure is the Siedlungsgenossenschaft, which everyone living on site is part of, and is responsible for everything that happens in the land belonging to Sieben Linden. The Wohnungsgenossenschaft is then responsible for those living in the houses on site, while the Freundskreis Ökodorf Sieben Linden deals with most of the links with the outside world, such as the seminars, and guest house. Many, if not most of the people living in Sieben Linden work on site, employed and paid a wage by one of these organisations. Decisions in these organisations are met using a variety of methods, such as the Forum (a method developed in a sister community, ZEGG), non-violent communication, mediation, and the Rätesystem (essentially a board of advisors, responsible for most non-essential decisions).

Another thing to mention, that we will talk a bit more about later, is the economic setup. As you just read, the community is organised as a Verein, and many of the people of the community are employees of this Verein. With their wages, community members then pay about 200€ rent, and about 100€ for food and cleaning material. Costs are thus extremely low, but the economic model is ultimately the same model of wage labour that is to be found in the outside world. Individuals work for their own private wage, and pay rent/costs to be in the community. Although costs for the essentials is done a little differently. You pay 100€ a month with which you can eat the meals prepared three times a day in the Sonneneck, or take food (or hygienic materials) from the community storehouse. Another element that sets this community apart economically is that children are raised in economic solidarity, so parents don’t have to pay the community the costs for their upkeep.

To join the community, you first take part in some of the various Kennenlernwochen (weeks to get to know the community), and slowly get to know most people living here. When you decide you want to move in, the community has a vote. If 2/3’s of people on your side, you’re good to move in. To join the community comes with an entrance fee of 11.275 or 12.000 Euro, depending on if you live in a house or a trailer. From the Sieben Linden website; ‘Our aim is to distribute the responsibility for the material side of the project to all project members, and to include only people who are prepared to share in this material responsibility. If there are people fit into the community and are committed to the project, but do not have this capital, these community shares can be financed by solidarity or personal loans.’

Mitarbeitswoche & Ecosystem Restoration

To come and stay in the community for a while, you need to either take part in a seminar, or join one of the Mitarbeitswochen, where you come and help with the work for a week. The type of work you do depends on the time of year you come. There are weeks focussed on working in the garden, weeks focused on maintenance work, and in Autumn there are weeks which are focused on harvesting and preserving fruits for the winter. My Mitarbeitswoche was focused on working in the forest. As mentioned above, Sieben Linden has 75 hectares of land that is dedicated to forestry. Right now, the majority of it is pine monoculture, but over the last 20 years work has been underway to transform it into a mixed forest. Through the year most of this work is done by one forester alone, but a few times a year she get a group of people to come help, so bigger projects can be undertaken.

The previous year I had already worked in the field of ecosystem restoration, but the conditions there were very different. This project was called Sunseed, and was in a semi-arid region of Andalusia, Spain. There, the biggest factor was always water. The first question was always ‘How do we ensure that everything we plant will get enough water to survive the harsh desert conditions?’ The landscape restoration in Sieben Linden was dealing with a wide variety of factors. Water was definitely one factor (with Germany now more regularly going through long dry periods in the summer, and north Germany’s low quality sandy soil, prone to drying up) but it is not a factor that takes overwhelming precedence over the rest.

Other consideration included things like what to do with the pine trees that were already there. Some thought that they should all be felled and the reforestation started from scratch. One reason in favour of such an action is that their needley foliage slowly raises the acidity of the earth, making it less favourable for the deciduous trees that are to be introduced. But on the other hand, bare earth leaves the young saplings more exposed to the elements in the precarious years of their youth. Over the years a number of methods were tried, and to me it seems like a mix of both methods was working well, selected felling of the pine. Another factor that was important was the wild animals in the area. Family of dear were often found to be chewing through restoration efforts, but was the mice who were really running amok. These little creatures burying into the ground and chewing through the roots of the young trees proved a much more difficult problem to solve. The forester told us that she used to have pet mice and rats, and maintained that she didn’t want to use traps to deal with them, but it seemed like this resolution was weakening with each downcast report mice chewing through another group of saplings.

Our work in the forest was quite varied. On the first day we worked an area that had been levelled and planted anew, digging up grass that had taken over this plot. This grass, aside from making life difficult from the young trees by growing higher than the young saplings, provided the perfect hiding space for those pesky mice. Here the trees were still young, but the next day we were working a plot with groups of older beach, birch, oak and larch trees. Our work here consisted mainly in stunting the growth of the alder buck trees. The alder buck tree (which is actually a bush) is native and provides protection against grazing deer, but it was growing too virulently, giving the beech and oak too much competition. So we went deep into the thicket, snapping, cutting, and sawing the bush down to size. On the final day did some of the nicest work of landscape restoration, planting trees. After choosing a few cosy spots, we dug deep into the sandy earth, excavating new homes for a family of elm, cherry and hazel trees. Who knows how these trees will get on. The first few year are particularly perilous. But the ones that do survive will most likely outlive those who planted them, supporting millions of little creature in the process.

Ecosystem restoration is spiritual work that requires connecting with the consciousness of Pacha Mama for any chance of success. It calls for constant observation of the myriad of life that exists within an ecosystem, consideration of the seemingly infinite connections that exists between all lifeforms in the forest (or desert, meadows, etc.). It requires seeing each ecosystem as an organism in its own right, that nothing in the forest is independent from any other part; that all are part of the same web of life, and that we too are a part of this web.

Eco-economics & Commercialisation

While the work of the Mitarbeitswoche was a joy, the social organisation behind it was something that requires reflection. To take part in this Mitarbeitswoche the standard price was between 110€ and 150€, depending on what room you wanted. If you wanted to take a day off to have a look around the community, that cost another 28€. If you wanted to use the sauna, that was another 5€, if you didn’t bring your own bedsheets, that was another 5€. That being said, if you weren’t able to pay such prices, there was a reduced rate of 50€. But still, that is 50€ to come and work 6 hours a day for a week. Most of the group seemed OK with the arrangement, but to me the whole model seems a little absurd, and not helpful for the wider movement. If the Buddha had said ‘I have discovered a way of living that frees you from suffering, just pay me 200€ and I’ll teach you the dharma’, I don’t think Buddhism would have become movement it is.

But Sieben Linden are by no means the only eco-village to make people pay to come and work for them. It is a growing trend among eco-villages. Generally the larger and more famous you are, the more likely you are to charge money for access to the community. Tamera, arguable the most famous European eco-village, charges 600€ a month to come and work in the kitchen 6 hours a day. If that sounds a little odd, it’s because it is. But if communities are willing to charge such prices to come and work for them, it’s obviously because enough people are willing to pay for it. This is a testament to the fact that eco-villages are exciting places of transformation, that people living in the city are willing to spend their time and money to come and experience it for themselves. But just because you can charge people to come and work for you doesn’t mean you should.

Eco-villages see themselves as places of social transformation. The idea is to create new modes of living, proving that it is possible to live in ways that are more harmonious and less harmful, so that others can adopt these new modes of living. [And one guest at the time was a young Turkish man who told me, ‘I want to live in an eco-village one day but there’s nothing like this Turkey. It’s one thing having an idea in your head of what its like to live in an eco-village, but its another thing being here, eating lunch with people who are actually doing it, seeing it work. It means a lot just being here.’] But by making it prohibitively expensive to spend time on them, it means you are only going to reach one section of the population – the section that is already interested and willing to spend money to go and work for the eco-village. If eco-villages are serious about their goal of transforming all of society, they should be making the barriers to entry as low as possible. They should be convincing people to come and get inspired to do something themselves.

What’s more, part of the eco-village movement is to work toward a more harmonious, sustainable, economic organisation. One of the main causes of the ecocide is the capitalist mentality; a mentality that puts a price on everything. Actions, objects, people, time, nature become commodities to make a profit from. Part of creating a better life is overcoming this mentality. Within the movement you find strands of people trying to create alternatives. The Kommune movement generally has some form of shared economy, and various people I’ve met try to live Tauschlogikfrei (free from logic of exchange). This is the idea (circulating at various festivals, climate camps, and communities) of cultivating an attitude of pure giving. Giving for the sake of giving, not to get something in return. This logic is the antithesis of the capitalist logic, disrupting our commodified understanding of the world, and a powerful antidote to a society built on selfishness.

That being said, although the formal structures at Sieben Linden make being a guest complicated, it is possible. If you get a Sieben Lindener to take you on as a guest, and cover your costs, you can stay at the community outside of the Mitarbeitswochen or seminars. And there are some very hospitality people living in the community. During my first week I made friends with a very nice woman who invited me to stay as her guest for a while, before putting me onto her friend, another very nice woman, where I stayed for another while. I helped out with a few odd jobs, but mainly had the chance to explore some of places in Sieben Linden that there wasn’t time for during the working week.

Another thing to mention about the above criticism is that I never had to deal with the finances of an eco-village. And to be clear, the people of Sieben Linden are not getting rich from the guests that come and stay. Most lead pretty simple lives, in Bauwägen or modest apartments. Everyone has to work for their daily bread, and many work for the community for a wage that is by no means high. The cost of living at the community is low, but the world outside is not, and everyone still has connections to this outside world. And as much as you can work toward a state of independence, it’s difficult to totally free yourself from the global capitalist markets. If you want to visit your elderly mother in Hamburg, that’s a 50€ round trip. If you want to buy something that’s not produced by the community, it also costs money. There are no simple solutions, and the difficulties in trying to escape the capitalist logic are manifold.

Another problem for the more famous eco-villages is the amount of request they have from people to come and stay. If they were to take on all the people who want to come and stay (some communities getting thousands of requests in a year) then the community wouldn’t survive. The social life is already generally more than what most people are used to, without having hordes of strangers constantly passing through. A group of volunteers brings new energy and excitement to a community, an army of them would overwhelm a community space. However, this does not necessitate taking money from people. Instead you simply set the number of volunteer you are comfortable with and have a waiting list for any numbers that above that. Charging money for to volunteers keeps the eco-village movement confined to the privileged in society.

On the second evening of the Mitarbeitswoche, they showed a documentary that was filmed during the early days of Sieben Linden. During that time Sieben Linden was more radical than today. They built their houses without the use of industrial machinery, and many worked for the community without taking a wage. People could come and work without having to pay, and helped build straw bail houses. Those times are now past and Sieben Linden is a much more professional operation (as it must be to meet the exceptions of people who pay 600€ for a week long seminar). The new buildings are still built according to the ecological philosophy of natural building, but with the help of machines, and by a contracted building firm rather than the volunteers. It seems like the natural progression. As people get older the willingness to live in experimental new ways is slowly replaced by a comfortable day to day.

One group cannot expect to radically transform all elements of life, all at once. Ecologically, Sieben Linden is a huge improvement on modern organisation, and is a model that we can all learn from. With so much energy going into environmental and community issues, it’s difficult to also deal with the question of new economic models. Also, I didn’t experience the past 20 years of experiment and debate that lead to the commercialisation of operations. Perhaps there is good strategic reasons for such a move. All the money goes into improving things in the village (a new house, new types of sustainable technologies) and allows for the smooth running of a centre of learning on sustainability. Even if this learning mainly reaches the privileged in society, it is the privileged who are often in the best positions to enact wider change. Every move has it’s advantages and disadvantages, and there are strategic advantages to partial assimilation to capitalist logic (as there are strategic advantages to completely resisting it). The most important thing is to be aware of what one is doing, and to consciously work toward overcoming the logic of commodification, accumulation, and profit, if not right away, at least in the long term.

From the Sieben Linden website; ‘We are aware that in matters of money we are in very delicate territory; in terms of personal financial biography; the performance oriented character of society; and finally the economic reality surrounding us, which we can not escape, that is to say we are a part of them. Building economic structures fully based on solidarity is a long road that we are always trying to walk anew.’

GEN International

During my time in Sieben Linden, the community happened to be playing host to the President of GEN International, Jennifer Trujillo, and her Catalonian boyfriend. Jennifer is younger than you would expect the President of GEN international to be, charismatic, and nice balance of serious and funny. Coming from her homeland of Colombia, she was doing a tour of various eco-villages around north Germany. Part of this was curiosity on her part, exploring some of the various communities that made up the GEN movement. But she also had the aim of strengthen the ties between communities. Along with her (secret) agenda of pairing Sieben Linden with a sister project in Mexico, she gave a presentation about eco-villages in the global south, and their link with eco-villages in the global north.

The presentation started with an overview of some of the projects that make up the eco-village movement around in the world. In Cameroon, an eco-village was undertaking huge work developing diverse types of agriculture and empowering people in their region. This was until the break out of the civil war forcing them to flee their homeland (military forces don’t look kindly on projects of people empowerment). Eleven members of this ecovillage are now living as refugees in an ecovillage in Portugal. She then introduced a project in Palestine that was trying to implement simple technologies for clean water, but whose efforts were being repeatedly sabotaged by the Israeli army. She talked of a project in Malaysia, where a young farmer decided to go against the trend of his peers. Instead of conforming to the commercial palm oil farming that was becoming the norm where he lived, he decided to set up an organic farm, getting back to the roots of the farming tradition of his region. His family were perplexed. Why would he live the simple life of a farmer when he could grow palm oil and have a big car and concrete house? The colonial expansion of industrial society brings with it colonial ideals of success. Stumbling across the eco-village movement, this Malaysian farmer was delighted that he was not alone, and that many other people around the world held the same values that he did.

Jennifer’s message from the eco-villages of the Global South to those in the Global North was: ‘Keep doing what you’re doing’. The positive effects of the eco-village movement in the Global South are two fold. First, by making yourself more autonomous, less reliant on systems of global exploitation, you are already making the situation better in the Global South. The wealth of modern society comes from the poverty of those outside its boundaries. The unending appetite for commodities from a minority of the world’s population means the dispossession of the majority. Dispossessed, this majority often have little choice but to work in slave like conditions, ensuring that our commodities are as cheap and profitable as possible. Rivalry from local elites over who gets to cream off the top of this exploitation lead to wars, like the one that forced the Cameroonian eco-village to flee their land. The next impact is that the eco-village movement is contributing to a slow change on our modern ideas ‘success’. It is now clear that it is not possible for everyone to ‘successful’ in the terms defined by modern society. The earth simply doesn’t have enough resources for everyone to be driving a car, or to be flying around all the time, or living in a town made of concrete. By consciously deciding to adopt values, new ideas of ‘success’ based on the ideal of harmonious living, it empowers others around the world to do the same.

After the presentation was over, I got into a conversation with Jennifer along the same lines as the one I had with Declan Kennedy, that is, how is the eco-village movement to grow even bigger. How can this movement of pioneers become a mass movement? She told me that since its foundation GEN had existed without a ‘business plan’. While my anti-capitalist soul slightly recoiled at the use of corporate terminology, what she meant was clear – until that point, the movement lacked a clear plan of action, a clear vision for how it would expand. That was something that she, and her new colleagues at GEN International, were in the process of changing. While not going into too many details, one point I found interesting was the idea of building partnerships with mainstream educational institutions. One of the main aims of GEN is educational, it is a network set up to teach others how to organise sustainable, autonomous, and ethical communities. But one of the biggest problems is how to reach people. Right now eco-villages remain something quite niche, only really reaching people who are already interested in the idea. But if GEN were to partner with mainstream universities, something that Jennifer said was in the works, then straight away this increases the potential reach to essentially all middle class youth.

When I was finished college, I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to do. I knew mainly what I didn’t want to do, and I knew that I was to go to college. That is what is expected of many young people today. The idea of joining or setting up a community in which people empower themselves and live sustainably was something that I didn’t even imagine was possible. But if (alongside maths, sociology, and computer science, etc.) universities were to offer a course on eco-villages, a course that would not only show that such a life was possible, but also teach the practical elements involved for making it possible (permaculture, natural building, non-violent communication, etc.), then I know that I would have chosen that course, and a lot of my friends would have chosen that course. If the eco-village movement can begin to form partnerships with mainstream educational institutions then I think we would see an explosion in the number of people who would choose this life for themselves.

For more information: https://siebenlinden.org