Agroforestry is a method of land management that incorporates trees, bushes, annual & perennial crops, and animals into a single agricultural system. This idea may seem strange to some. What many of people imagine when think of agriculture are huge monocultural fields. However, although relatively unknown in modern society, agroforestry is nothing new. It has been practised by human beings for many thousands of years and is probably the most ancient form of agriculture. Early farming was generally about managing complex semi-natural systems, rather than destroying local ecosystems to grow a small number of crops. But the rise of large centralised civilisations created the need for a food source that was easy to transport and store. Farmers that were in the vicinity of these civilisations were therefore compelled to grow grain to pay tax. This meant that the complex semi-natural systems had to be simplified, with farmers moving toward more labour intensive cereal production. But although farmers began moving away from more natural forms of land management, this didn’t mean that they began creating the kind of monocultural deserts that that we know today. While they did become more grain orientated, they still incorporated their grain production into polycultural systems. For example, a well known agricultural practice during Roman times was the arbustum gallicum, in which cereal crops were grown in between rows of trees (olive, chestnut, mulberry), which would also be trellised with grape vines.

It is only in the last 150 years that we see the rise of the completely monocultural systems. In order to allow space for industrial machinery, trees had to be removed from the system. And the transformation of farming into a purely commercial activity, with farmers no longer producing for themselves but instead solely for the market, meant that producing a variety of crops made less sense than producing one crop en masse. And because monoculture crops, living on a diet of synthetic fertilisers, are prone to attack from all manner of lifeforms, modern farmers began to spray their crops with toxic chemicals. As the 20th century progressed, the destructive nature of this new form of monocultural industrial farming, obvious enough from the beginning, became impossible to deny. The soil has become infertile, devoid of microbial life. Insect populations have been decimated. And agriculture is now one of the of main contributors to fossil fuel emissions worldwide. While indigenous peoples around the world have continued to practice agroforesty in pockets, it wasn’t until the 1970’s that modern society began again to experiment with more complex, forest-inspired, agricultural systems. Little by little agroforestry has grown in popularity and awareness. While today it is still mainly practised by a relatively small group of enthusiasts, a consensus around the need for a new type of agriculture is being formed. Even mainstream politics is starting to take notice, with Green Parties throughout Europe calling for European farmers to begin the transition from conventional farming to agroforestry. The winds of change are blowing back in the direction of this bio-diverse and productive form of land management. This article is to give a basic introduction to some of the ideas coming from the field.

Plant Cooperation

The first principal of agroforestry is that plants work and grow best in co-operation with each other. This idea goes against the conventional agricultural view, which sees nature solely in terms of competition (perhaps because of the capitalist ethic of personal gain that dominates our time). The conventional logic is that there is X amount of water/nutrients/sun in an area and all plants are competing for these scarce resources. And, from one perspective, there is a certain amount of truth to this idea. Plants do compete with each other, and the success of one plant can mean the demise of another. If this was the extent of our understanding, we may conclude that the best way to grow plants is to space them far apart from each other, ensuring that they receive the maximum extent of the surround resources. However, if we were to take a broader perspective, we would see that plants not only compete with each other, they also co-operate and form mutually beneficial relationships. They provide each other shade, nutrients, and protection from pests. Each plant plays a unique role in the ecosystem, which provides the conditions for all life to thrive. Like all living beings, plants are part of an interdependent web of life. Cut them off from this and they grow weak, and need constant human intervention if they are to survive.

So the field of agroforestry looks at how plants co-operate, rather than just how they compete. What this means in practice is putting plants together in mutually beneficial relationships: ‘companion planting’. Sometimes these companion plants provide a yield, other times they are there to contribute to the overall health of the ecosystem. Examples of ecosystem function are things like providing shade, attracting beneficial insects, or providing crops with medicine. Because medicinal plants don’t only have medicinal benefits for humans, the effects for other plants/animals in the ecosystem are often similar. For example, rosemary has anti-bacterial properties, so planting it next to a tree will help protect it from infection. Another ecosystem function may be to provide ground cover. This is important because bare soil is at the mercy of the elements, quickly drying up and being damaged by the sun’s UV rays. Planting clover not only protects the soil, but also helps to fix nitrogen in its roots. Another important role in to be played in an ecosystem is that of ‘dynamic accumulators’: plants with deep root systems that dig down, bring minerals to the surface and making them bio-available to other plants. Often times, you don’t need to plant anything at all, as many wild plants that come to the garden are ‘pioneer plants’ and will start improving the soil in all kinds of ways if we leave them to it.

It is important to understand that plants form mutually beneficial relationships, playing different roles and filling different niches in a living ecosystem. Because of this it is they grow better in more complex polycultural systems. Not only that, but these more diverse system provide habitat to millions of micro-organisms, fungi, and animals that we depend on to make the soil fertile.

Trees

When bringing trees into an agricultural ecosystem, there are many different factors to consider. The first, of utmost importance to agriculture, is: what kind of yield can these trees provide? Fruits and nuts are the obvious ones, but the possibilities go much further than this. Some trees (such as white mulberry, or birch) have edible leaves, providing an abundant source of green leaves for a tiny fraction of the work than an annual crop like lettuce. Some provide medicinal oils and resins, like camphor and pine. Timber is another important yield that we get from trees. Other types of yield include things such as: edible cambium (from trees such as elm, beech); teas (from trees like linden); or tar/pitch (from pine trees).

But when considering the role of trees in an agroforestry system, yield is only the first thing to consider. Trees also play an essential role in a functioning ecosystem. Through the natural course of its life, a tree provides food and habitat for millions of little creature in its surroundings, little creatures that are essential to the growth of your crops. Another role, which trees such as alder or mimosa can fulfil, is fixing nitrogen in the ground (or rather they form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen fixing bacteria in their roots). Nitrogen, the most abundant gas in air, is one of the most important elements in determining soil fertility, and so plants that fix the nitrogen in the soil and make it available to other plants are incredibly important. Another important function that trees play are as bio-mass accumulators. Because when trees photosynthesise, they capture the energy of the sun, and when they lose leaves, branches, etc., they give this captured energy further along the food chain. This is the ultimately basis most life on earth, and so we want to maximise this process in our agricultural systems. By pruning trees, or simply allowing their leaves to fall, we allow a layer of humus to develop that provides nutrients to the rest of the crops. So instead of crops losing out on nutrients by growing next to trees, as conventional agriculture imagines, annual crops gain from the extra nutrients produced by trees every year.

Another important role that trees play in the ecosystem is to provide shade to the many types of plants that don’t thrive or survive in full sun. However, here we can take a step back, because, while it is true to say that plants form and thrive through mutually beneficial co-operation, there is also an element of competition between plants – in particular when we are looking at a plant’s sunlight requirements.

Canopy Layers

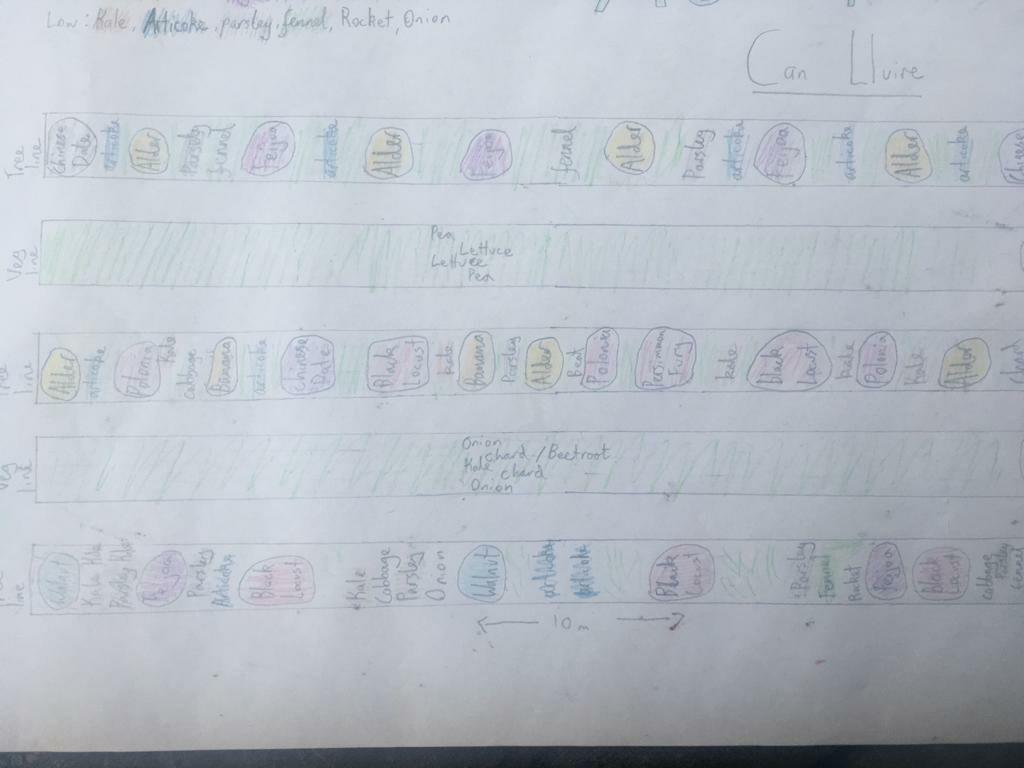

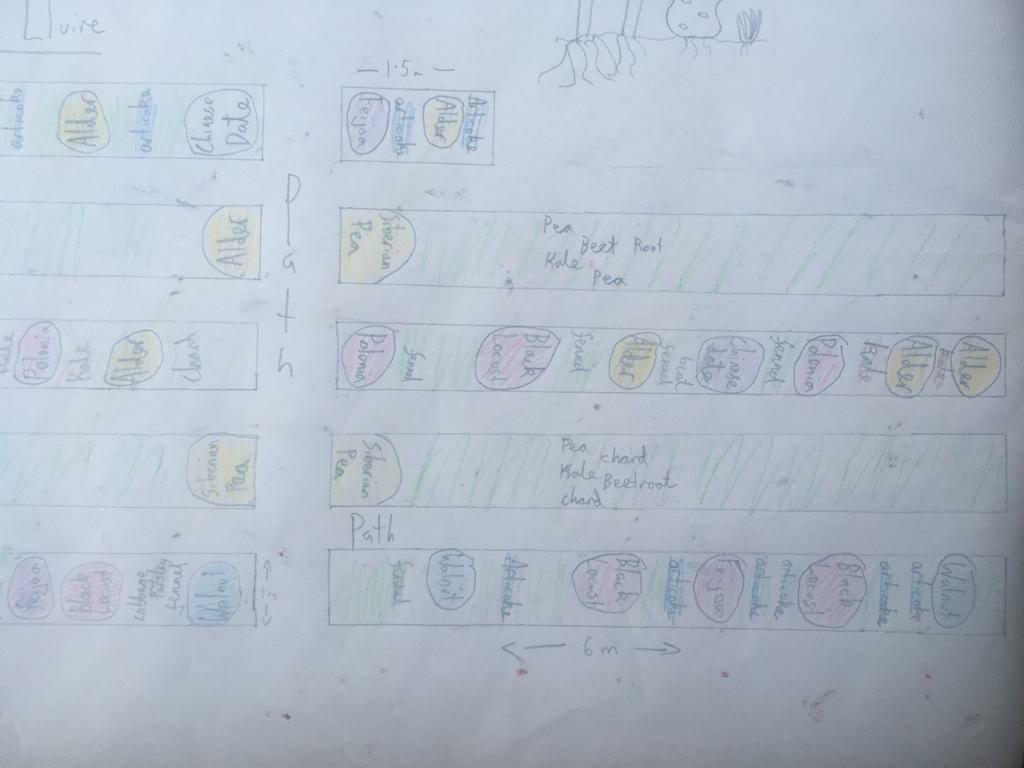

For this reason, designing the various canopy layers of your agroforestry system is essential. Just as in a natural forest, an agroforestry system has a range of plants with different sunlight needs. On top of the canopy are what are called the emergent plants – plants that need full sunlight. In a natural forest, these would be the trees that you see peaking out over the top of the canopy. Next are the high canopy plants, which dominant the top of the canopy and also need full, or almost full, sun. Then come the medium canopy trees, which don’t need full sun but need at least 50-80% sunlight. These trees don’t often do well in mature forests, as they can’t compete with the high canopy trees on height, instead appearing in border areas or forest clearings. Finally we have low canopy trees (and here we can also include bushes, as well as annual and perennial crops), that like (or can at least survive) partially, or entirely, in the shade. To maximise yield and the allow all plants to thrive, it is best to incorporate all elements of the canopy into our system. If we don’t provide the proper conditions for our plants, they become prone to pests and need constant attention.

Sunlight Harvest

Harvesting the sunlight is an essential element of agriculture. As mentioned, through photosynthesise plants transform photons of light into sugar, thus making it available to all other life forms. By maximising the amount of photosynthesis in a piece of land we maximise the amount of energy that is captured, stored and made available to other life forms. For this reason, planting the different layers of the canopy multiplies the productive output of a piece of land by the amount of canopy layers that I have. Instead of planting one crop in a piece of land, covering the low canopy area, you plant four crops (also covering the medium, high and emergent layers). These plants do not compete with each other for sunlight (as their sunlight requirements are different), and actually benefit from one another, as often lower and medium canopy trees need at least partial shade. This only require a bit of planing (and proper pruning) to ensure everything will be correctly spaced to allow emergent trees to receive full sun, medium to receive 50% – 80%, etc. Generally in a system we want some distance between the larger emergent and high canopy trees, with the medium and low canopy planted in between. Generally the ratio of plants in a system is something like 1 – emergent canopy/ 2 – high canopy/ 3 – medium canopy/ 4 – low canopy.

This can result in, compared to conventional farming, incredibly dense planting. But once we remind ourselves that plants not only compete, but also form mutually beneficial relations, and occupy different niches in an ecosystem, the idea of high density planting begins to make sense. For proof of this we can look to the natural world. The most fertile and productive lands in the world are the natural forests and jungles, where plants grow so densely as to create impenetrable walls, and, without human intervention, create and sustain orders of magnitude more life than the fields of modern agriculture.

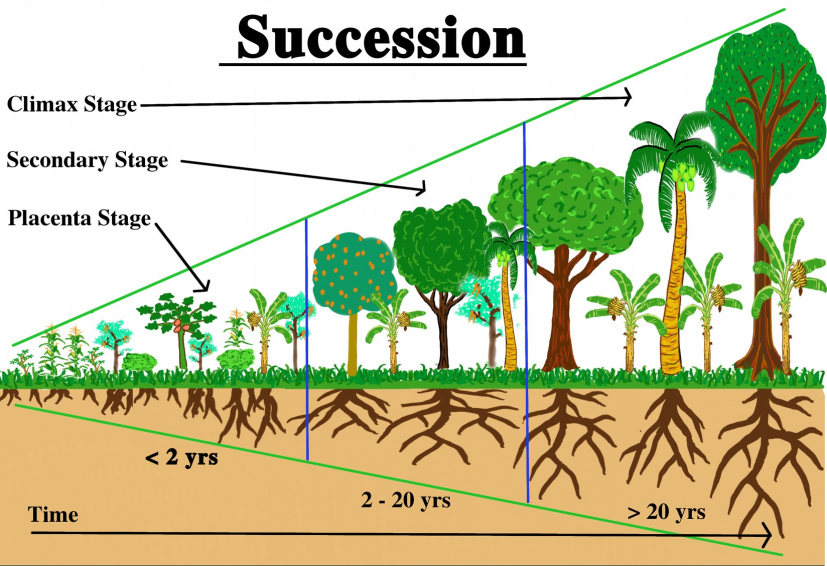

Succession

Another reason for the dense planting is that many agroforestry systems plan for various stages of plant succession. While this small row may appear to be overcrowded, these trees all grow at different rates and will thus reach maturity at different times. Some of them may be planted for the early phase of the life cycle of this system (in order to provide shade, fix nitrogen, or accumulate biomass, etc.) but will then be cut down after a few years to allow other plants to prosper (leaving you with a solid piece of a timber). So in the beginning of the lifecycle, we may see fast growing fruit trees (such as apple or pear trees) or bio-mass accumulating trees (like alder, or euculyptus) occupy the high and emergent canopies; but when these trees are chopped down, or reach the end of their natural life cycle, the slower growing, longer living, trees (having growing in the shade for many years) get there opportunity and shoot into life. These are called climax trees, the trees that can live for many hundreds of years and are the trees that dominant the old growth forests. The climax trees are what are planned to be the dominant trees at the end of their successional cycle. They may provide a yield, or may simply be there as the culmination of a restored ecosystem. When the piece of land has reached this stage of growth, we could then selectively cut some of the canopy to allow more light to enter, starting the whole process again, or move on to another piece of degraded land to begin working (and restoring) that. And this is one of the most important elements of agroforestry, it is not only about feeding ourselves but also about restored degraded ecosystems.

Perennials

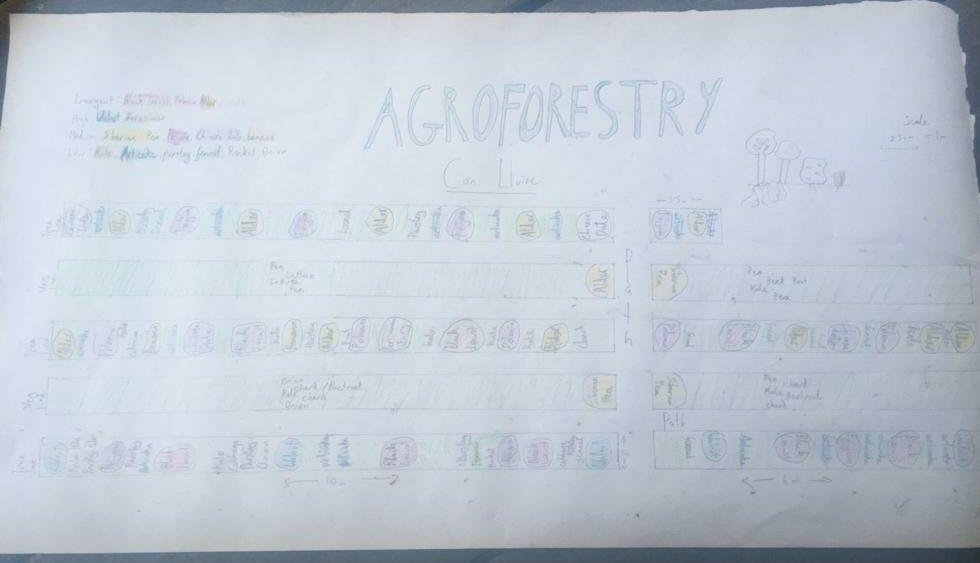

Another thing to mention is the importance of perennial plants. In an alley crop system (like the example given in the pictures) the tree lines can also be planted with vegetables. However, as we should not disturb the soil surrounding the trees too much, it is better to plant perennial vegetables or herbs. Perennials are plants that live for more than two years. Trees and bushes are perennial but there are also different perennial vegetable crops (such as artichoke, rhubarb, or asparagus). Although the modern human diet largely consists of annual crops and grains, there are many advantages to switching to a more perennially based diet. For one, they require much less work, as you don’t have to plant them anew year by year. You merely plant them once and then you harvest for many years. Perennials also have deeper root systems than annuals, and so pull up more nutrients and water from deep below the surface. Another advantage, perhaps the main advantage, is you don’t have to dig up the soil every year. The longer the soil stays underground, the more communities of micro-organisms, fungi, and animals that can move in, the healthier and more fertile is your soil. Our annual crop cultivation reduces the amount of topsoil each year, leeching nutrients and not allowing a layer of humus to form. This can only happen for so long before the soil is depleted and we have to start taking fertile soil from somewhere else (or put petrochemical fertilisers in the ground like conventional agriculture). With agroforestry, not only do we not lose precious topsoil; topsoil actually increases year after year as the foliage, roots and fruits of the plants form layers of humus (as well as all of the contributions by microbial life in the ground). These are just some of the reasons why many people are looking to incorporate not only trees and bushes, but as many types of perennial crops into their system as possible.

In Between the Lines

However, while there are many advantages to perennial vegetables, this is not to say we have to ditch annual crops altogether, and it is entirely possible to incorporate annual crops into an agroforestry system. One popular method is alley cropping: growing annual crops between the tree lines. Here as well it is possible to incorporate some of the ideas of plant co-operation. For example, we can incorporate the different canopy layers into a vegetable patch, such as in the mayan inspired method of the three sisters. Here, pumpkin is grown along the ground, spreading out between stalks of corn. Growing on the stalks are corn are lines of beans. And it is not only vegetables that can be grown in between the lines, you can also grow grains, or crops like hemp, or even green manure. Like the bio-mass accumulators, green manure are plants that are grown specifically to provide nutrients to other plants (or animals). The most popular plants for green manure are: types of grasses (such as Sudan grass), plants from the nitrogen fixing legume family (such as alfalfa or clover), and the winter hardy brassica family (such as mustard or turnip). These highly nutritious plants can then be added to the tree lines, to provide nutrients and mulch. Mulch is a word for ground cover, and its use is very important in many agroforestry systems. Bare soil leads to water evaporation, harm from UV rays, and exposure to wind and other elements. Covering the soil with mulch, on the other hand, conserves heat and water, as well as providing habitat for the many beneficial insects and micro-organisms that work to make a healthy soil.

Pruning

One important element of agroforestry is pruning. There are many different methods for pruning trees, but we can look at one method to see an example of some of the considerations that going into pruning. The most basic things to consider when pruning plants are maximising sunlight exposure and making sure it is easy to harvest. But in syntropic agriculture (one type of agroforestry) pruning is also used to encourage the maximum growth of plants in a system. Plants, like all living creature, go through various stages throughout their life: focusing on growth early on, later on flowering, before finally going to seed. If we want to harvest fruits, the plant obviously has to be allowed to go through the full cycle. But if want to focus on the capture and storage of energy (particularly important for the bio-mass accumulators), we can selectively prune them to ensure they don’t move on to the flowering and fruiting stage. This means that the plant stays in the growth stage of their life cycle and continues to maximise photosynthesis. And this not only has an effect on the plant itself, but also all the surrounding plants. Plants that share soil also share a network of mycorrhiza. Through this network they exchange hormones. So more plants in the growth stage of their life cycles means more growth hormones in the ground, which has an effect on other plants as well, stimulating them to grow.

Animals

If you don’t need to mulch your tree lines, you can give the green manure to the animals. Because, just like in a natural forest, animals are an important part of many agroforestry systems. We have already mentioned that wild animals (such as bees, worms, etc.) play important functions in agroforestry, but many people also incorporate domestic animals into their systems. Grazing animals (such as pigs, cows, or chickens) not only play an important role in the ecosystem by digesting organic materials, making them bio-available to the plants, they also provide a variety of yields (like wool, eggs, dairy, or meat). One famous examples of silvopasture (a mixed system of grasses, trees, and animals) is the dehesa systems in Spain and Portugal. The dehesa is a man made savannah, consisting mainly of oak tress (although other trees like beech or pine may also be present), wild grasses, and grazing animals (such as cows and pigs). This type of system provides a huge diversity of yields: mushrooms, honey, cork, wild game, and firewood. And unlike the industrial meat factories, that have an incredibly detrimental effect on local and global ecosystems, the dehesa is a ocean of biodiversity and a huge carbon sink. Whatever our ethics on the use of animals in the human diet, it is clear that animals are an essential part of a healthy ecosystem. To exclude them from an agroforestry system would be to leave one link in the nutrient cycle unconnected.

Diversity of Agroforestry Systems

One final point to mention is that what we have looked at in this article was mainly one type of agroforestry system: alley cropping – the planting trees and crops in straight rows. What’s more we looked at one type of alley cropping, a method of dense and diverse planting largely inspired by the syntropic farming of Ernst Götsch. But this is by no means the only way doing agroforestry. There are many different ways of combining animals, trees, and annual and perennial crops into a single system. We could plant in more highly spaced, less diverse, alley cropping. We could plant in a more traditional orchid systems, with more dispersed trees and crops growing in between. We could plant in ‘guilds’, dense groups of companion plants in circular clusters. We could also incorporate trees into our systems in a huge number of different ways: providing windbreaks; creating hedgerows; preventing erosion on terraces; preventing flooding; or preventing evaporation of rivers or other bodies of water. The possibilities are limitless. But the most important thing to start this journey is realising the fact that we must work with Nature, rather than against it.

The Future of Farming

Whatever way we look at it, trees are an essential part of healthy ecosystems in temperate climates, and it long past time that we realise that function of agriculture is not only to provide human beings with food, it is also to create and maintain healthy ecosystems. We cannot have one without the other. While this does mean that we have to rethink many of the farming practices that have arisen in the last 150 years (industrial machinery, petrochemical fertilisers, and toxic pesticides), this does not mean that the situation of farmers or consumers will worsen. Quite the opposite. Once they have established themselves, agroforestry systems are considerably less work than energy intensive monocultural farming. After the initial phase, they also require a lot less inputs (providing all the natural fertile and pest control themselves) meaning less costs for farmers. Along with being less work and having less costs, agroforestry systems also provide higher and more diverse yields than monocultural systems. Instead of a farmer having one crop on their land, they have many different crops, multiplying the yield. And a more diverse yield means that commercial farmers are in a better position in case of one crop having a bad harvest, or fluctuation in market prices. A diverse yield also means it will once again be possible to be largely self-sufficient, leading to a more autonomous life for farming communities. Consumers will also benefit, having access to food grown in living soil and without toxic chemicals. Finally, everybody ultimately benefits from the restoration of our ecosystems and ensuring the fertility of the land upon which we all depend.

Challenges

However, even though the way forward is clear, there are also some considerable stumbling blocks to the wide scale adoption of agroforestry in our current society. The first is that of the wide-spread misconceptions around agriculture, such as that plants only compete with each other or that all crops much be grown in full sun. However, just as these misconceptions spread with the wide-scale adoption of industrial monocultures over the last few years, so too will they recede as agroforestry systems once again establish themselves and prove their worth. Another difficult is with the difficulties for marketisation of agroforestry systems for commercial farmers. There is no doubt that selling one crop in bulk is easier than selling a small amount of many different crops. However, the development of initiatives like Community Supported Agriculture over the last few years have slowly been changing the relationship between farmers and consumers. And this is also imperative. Along with transforming the way we do agriculture, we need to transform the economics of agriculture, with people again eating regional, seasonal food. The final, and most dangerous, of the stumbling blocks on the road to the large scale adoption of agroforestry, are the vested interested of the multinational corporations that lay claim to vast tracts of land and exert huge control over national governments. While it is ultimately in no-one’s interest that we continue down the suicidal course of conventional agriculture, from the limited perspective of these corporation’s short term profits, conventional agricultural works very well. Farmers, instead of receiving everything they need from a functioning ecosystem, have to buy a large variety of products year after year from corporations like Bayer/Monsanto. These corporations have proven that they will go to any lengths to prevent the loss of their short term profits, and national governments generally work in their interests. However, although the power of this small minority of people appears great, far greater still is the latent power of the people, all playing their little part to transform society and restore the proper balance with the natural world.

*The photos are mainly taken at Can Lluire in the Alta Garrotxa region of the Pyrenees.*