Climate camps first emerged in the 2005 in the UK. They are similar to music festivals, in that they are gatherings of people camping for a short time in a remote area. But instead of coming together around music and hedonistic excess, climate camps are gatherings of people interested in ecological activism. They are places where those involved or interested in climate action can share knowledge, skills and experiences; places where people new to activism can come and learn about some of the different initiatives and struggles going on around the worlds; places for people already engaged in activism to link up with others and raise awareness for their cause. The camps are non-commercial, instead functioning on a solidarity basis. The camp is open for anyone to come and stay, and there are three meals provided every day. Everyone who can contribute funds is expected to (at Leipziger Land the recommended donation was 3-5€ a day for using the camp facilities, and the recommended food donation was 5- 8€ for breakfast, lunch and dinner), with the amount that one contributes based on their financial standing. However, at no point is there someone looking over your shoulder to see if you have given something, and so people are trusted to contribute what they see as fair.

The organisational structure is anarchistic and participatory, with an emphasis on inclusiveness. At Leipziger Land the main theme was decolonisation of the climate movement and there was an emphasis on listening to voices from minority groups and people from the global south (although a large majority of people at the camp were white privileged Germans). There were ‘safer spaces’ on the camp for LGBTQ and people of colour, and there are many family facilities to ensure that the camp is as inclusive as possible. What I found particularly nice at at Leipziger Land was that a local Trade Union set up a stand on behalf of the local workers of the coal mine. The environmental movement is sometimes criticised as being dominated by privileged people who are unaware of the struggles of the more disadvantaged in society, and so having a voice of the working class from the surrounding area was important. The trade union representative at the stand said that he would be happy for the coal mines to close tomorrow, but there would clearly need to be some alternative for the many people in the area relying on it to put bread on the table (if I understood him correctly through his thick sächsische dialect).

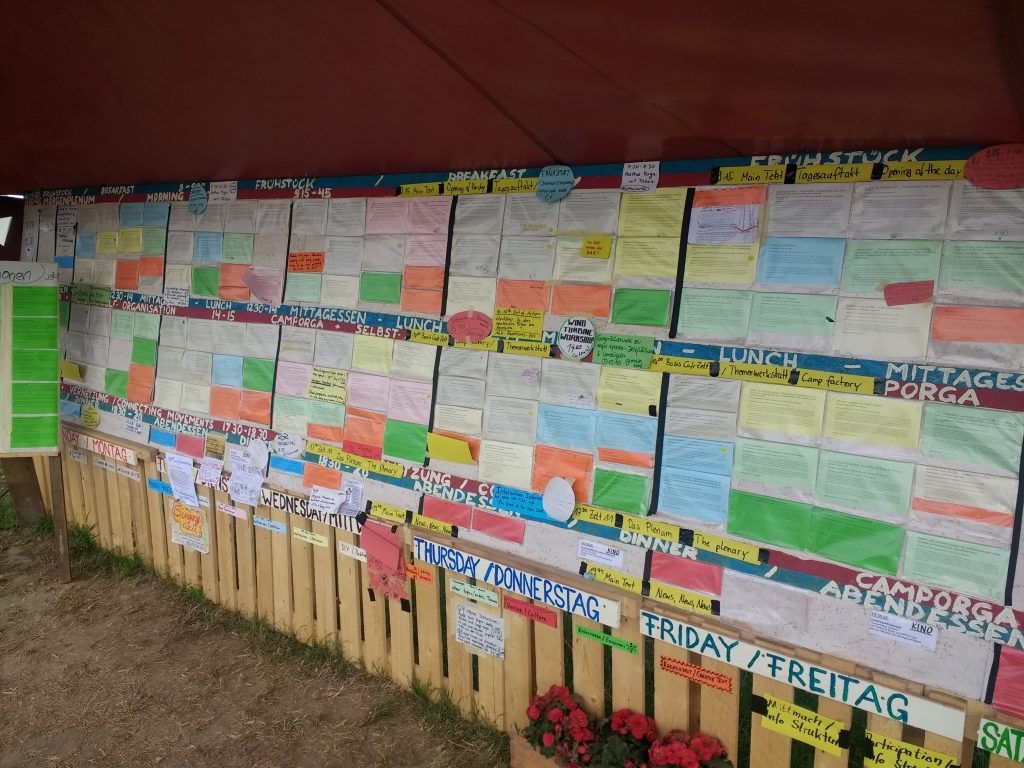

At the camp, there are no permanent ‘staff’ or organisational committee. Instead everyone is invited to open daily plenaries to discuss how the camp is functioning, and is encouraged to do at least one ‘shift’ to keep the camp running smoothly (with the type of work to be done ranging from cooking, to helping people at the info point, to cleaning the compost toilets). There is an event programme filed with talks, workshops, and other activities that is largely arranged beforehand, but the event timetable generally has open spaces for those who decide spontaneously that they would like to share knowledge about something or host a workshop. Since the time of their emergence, climate camps have been growing and spreading out all over Europe. In 2019 there were climate camps in Austria, Czech, Switzerland, England, Portugal, Poland, Italy, Belgium and a number of camps in Germany. Leipziger Land was one of these German Klimacamps, and took place at the beginning of August.

After getting a bus to Leipzig, and a train to the small town of Neukiritsch in the region of Sachsen Anhalt, I am greeted by a friendly stranger, a bit younger than myself, who had driven down to the train station to offer new arrivals a lift to the the village of Pödelwitz, where the climate camp is taking place. The village was about a 20 minute drive away and, on route, the guy who picked us up brings our attention to the huge opencast mine that surrounds us on all sides. A scar on the face of the countryside. Two huge pillars of white smoke can be seen in the distance. A short time later we arrived in the beautiful little village of Pödelwitz. Surrounded on all sides by trees, the village square was abuzz with people. Having not really known anything about this particular climate camp before my arrival, I was surprised to see that it was set up around the village itself. The village square acted as a centre point and meeting place for the camp, there was an open air cinema set up in a green area outside the church, the camp site in which I was staying was situated around the old train station. For sure, the main areas of the camp (event tents, cooking/eating areas) were on fields within the village, but Pödelwitz itself was very much a part of the camp. My idea of climate camps was that they were a meeting point for national and international forces. What I didn’t realise was that there was a very local dimension to the one, and the villagers of Pödelwitz played an active role in the organisation.

While many of the people at the camp belong to a semi nomadic milieu of climate activists, the people of Pödelwitz lived a more traditional rural life. However, they found themselves on the front line of a battle for climate justice when a coal mining company Mitteldeutsche Braunkohlengesellschaft decided their village needed to be destroyed in order to extend the coal mine. As the old train station can attest to, Pödelwitz was once more of a town than a village, and boasted around 700 or 800 inhabitants. But over the last few decades it has seen a steady decline. This is partly due to the same factors that is depopulating the countryside all over the world, and partly because MIBRAG has enacted a campaign of displacement, taking measure to oust the villagers from their land. This programme has been largely successful, reducing the village population to about 30 people, but these 30 people are the ones who have decided that their homes are worth defending. Despite the demoralising impact of seeing the disintegration of their community, and of seeing the countryside you grow up around utterly destroyed, a group of villagers organised themselves and set up the action group Pödelwitz bleibt! (Pödelwitz stays!) to resist to mining corporation. It is from this local action group reaching out to the activists in Leipzig that this climate camp emerged.Throughout the week the villagers offered tours of the village and talked about there campaign of resistance, and on the final Saturday of the camp there was a large demonstration, organised in support of Pödelwitz bleibt!.

And for those who wanted to learn about other struggles,there was a daily programme filed with talks and workshops. In the mornings and afternoons, there was generally about 8-10 events going on simultaneously, so their would always be a few things that you would find interesting. On the first day I went to a talk held on eco-villages. This talk was held by two people living in two different eco-villages in Germany, and consisted of an explanation about the emergence, the concept, and the values of the eco-villages. They talked about how these eco-villages are connecting with each other (with an introduction to the GEN network), as well as how these villages are beginning to connect with other rural villages and towns (sometimes offering ideas and advice to those villages faced with the problem of de-population).

The next day I borrowed one of the camp bikes and joined a group of people who were to cycle 15km away to visit a local eco-project. After a beautiful cycle through the countryside we arrived at Luftschlosserei, a project that had been established a couple of years previously. When we arrived, we were invited to sit under chestnut tree and eat a variety of delicious vegans cakes they had prepared. There they told us of their journey from city life to one based on an alternative mode of living, a process that they were still very much undergoing. On the third day I went to a talk on how anarchist theory may be helpful in plotting a course to fairer society. After this, I went to a demonstration of someone who had built a wind turbine at the camp using recycled or cheap materials (this turbine was providing power to charge phones).

Aside from the talks and workshops, there was a huge amount of other things to do at the camp. As you would would expect of any large gathering of people, music could be found all over. There was a concert in the main tent in the evenings, drum troops walking around in the day and jam sessions in the Kulturjurta (culture yurt). The Kulturjurta was built by a group of activists who live in Pödelwitz permanently, squatting a piece of Church land, and supporting the villages in their struggle. Aside from the yurt these people have set up some agriculture, as well as building a tree house way up high, and offered workshops in scaling tree (an essential skill for activists looking to block deforestation).

Directly opposite the yurt was an outdoor cinema that showed films are sunset. On the occasion I went to check it out, they were showing a film on the Neo-Zapatistas and indigenous struggle against de-forestation Brazil. A couple of minutes walk away from this, in a semi-enclosed square, was a few stalls offering crepes, vegan pizza, or tea/coffee. Also in this square was a workshop where one could learn about Low-Tech construction and repair (building a carrier for a bike, making a torch using recycled electronics, building palette furniture). On the other side of the camp was a bar area that opened up in the evening, selling drinks and playing techno (a ubiquitous feature of German social gatherings).

With the devastating effects of environmental destruction being felt around the world, it has become clear to many that something must change, and that governments and corporate elites are incapable of bringing that change. The last few years have seen the numbers of those participating in climate actions skyrocket. Hambacher Forst and Ende Gelände are impacting public discourse and policy here in Germany. Extinction Rebellion has made direct action and civil disobedience mainstream. Fridays for Futures is a signal of intention from the coming generation. The will for radical action is growing, and climate camps are places for people to teach, learn, and participate in radical action. We can expect their importance to grow in the coming years.

For more information: https://www.klimacamp-leipzigerland.de/en/