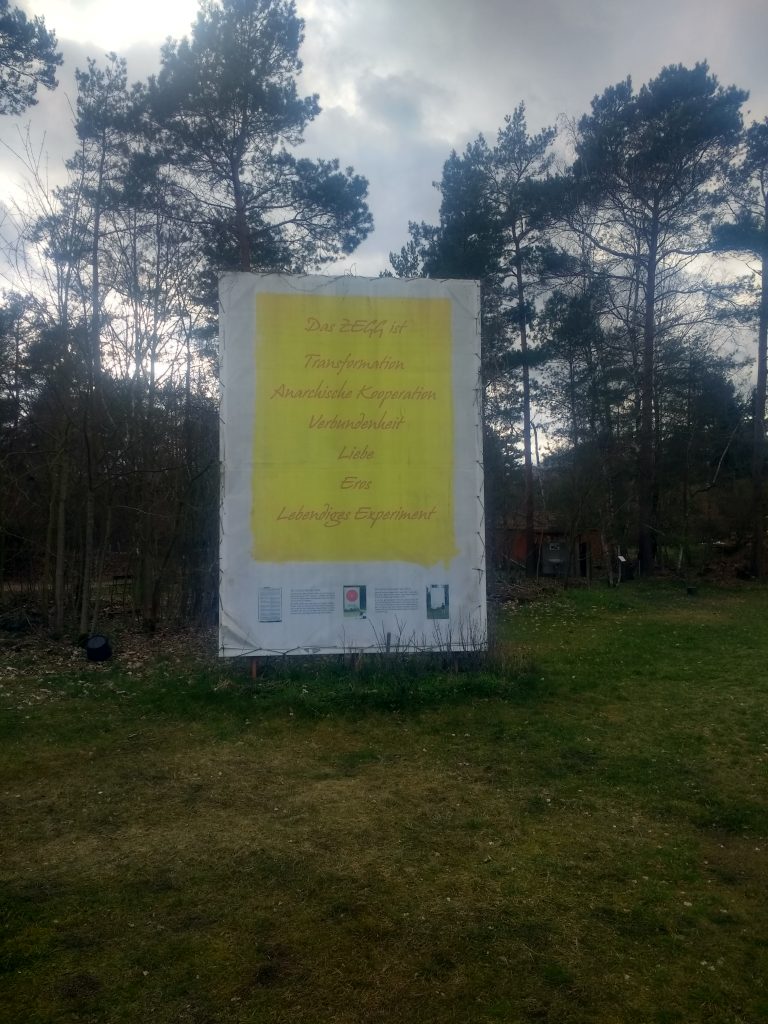

Tucked away in the Brandenburg forest at the edge of Berlin, das Zentrum für Experimentelle Gesellschaftsgestaltung (roughly ‘centre for experimental social transformation’), or ZEGG, is one of the oldest and best established eco-villages in Germany. Founded in 1991, ZEGG is a community of about 110 people (about 15 of those children) with the aim of creating a more loving, conscious, sustainable existence. As well as being a functioning community, it is also an ‘alternative centre of education’ where you can learn about all elements of sustainable living, with a focus on building new types of social relations. During the year there are also a number of weeks where people can come work in exchange for bed and board. Interested in getting to know this influential community, I signed up and made my way to ZEGG in the first week of March for the Frühjahresaktion (spring action).

History

The land upon which ZEGG is based has a long history, and has passed through many hands over the course of the last hundred years. First appearing in records in 1909, the space was then owned by a family of local farmers. In 1919 the homestead changed hands, being sold to a couple of families, missionaries and teachers who fled from German South Africa after the first world war. These families ran a successful commercial farm, selling their produce to the people of Berlin, until 1933 when one of the sons, a Nazi sympathiser, left his part of the farm to the National Socialists. Because of its ideal location, in the forest but close to the capital city, the Nazi put it into use for a variety of uses. First, from 1934, it was a training space for athletics competing in the 1936 Olympics. Later the Nazi’s would use the space as part of their Kraft durch Freude (strength through joy) programme. As part of this programme Germans were offered a a variety of state sponsored sporting activities, giving the Nazis control over the people’S leisure time (and making sure the population was fit, should a war break out). This lasted until about 1941 when French forced labourers were probably stationed here. In the final years of the war, the space functioned as emergency hospital bay for people with non-serve injuries.

After the war, it was briefly used as a base for troops from the Soviet Union, as well as housing refugees from the east. This was until 1949, when the newly created German Democratic Republic took over, and began using the space to train its new army of bureaucrats. Then in 1956, it took on its final form before it would come into the hands of the ZEGG community – training spies in the art of espionage. It was here that up and coming spies could learn everything they needed to know about the theory and practice of being a foreign agent, as well as how to sniff out spies within their own ranks. One might learn, for example, the finer points of the so called ‘Romeo’ method, in which agents would begin a romantic relation with a target. In 1988 when the spy school was shut down and the space given to the Potsdam local government. After the fall of the wall, the space lay empty for a few years until 1991, when it was acquired by a group of people who planned radical experiments in social relations.

This group was formed around the ideas of Dieter Duhm, one of the leading figures of the 68er movement, the German expression of the hippie movement. The movement was generally composed of students and young people who rejected the oppressive colonial society they found themselves in, and wanted to create something new – a new society, new types of social relations. With this idea in mind, Duhm founded the community project Bauhütte in south German, to create a space to experiment with non-violent ways of co-existing – with a key element of this being the ‘healing of love between men and women’. What this meant in practice was intensive group processes and ‘free love’, polyamory. The group considered their experiment a political act, and started to promote their new experimental ways of living in wider society. Unsurprising, this garnered much criticism from the church and the local press, who labelled them a ‘sect’.

It was in the midst of these controversy that a group of people from Bauhütte acquired the space in Bad Belzig and founded ZEGG. In the beginning about 80 people moved into the space and began with the process of renovation, making the space more sanitary, ecological, and liveable. The old coal burning central heater was replaced with a wood burning one, a natural waste water system was built. This is what much of the first few years was taken up with before it opened up to public. When things were in order, they began offering seminars on experimental modes of human relations. In the meantime, Dieter Duhm and Sabine Lichtenfelds, who inspired and helped create ZEGG but never lived there, founded the ‘healing biotope’ Tamera in Portugal. Today Tamera is perhaps the most famous eco-village in Europe, and began mainly from ZEGG members, who slowly started to migrate to Portugal over the next years, partly reducing ZEGG numbers. This was only to last a few years though, and since then, ZEGG has continued to grow. Today ZEGG is a well organised, tightly functioning community of around 110 people.

Space

ZEGG is based on a large settlement with a large number of building and features. Many of the buildings were built in the time before ZEGG, but there are also a few new buildings. The main building is the Uni, a huge multifunctional building at the centre of the site. This building acts as a residence for community members and guests, seminar space for the various courses, as well as many other types of rooms (living spaces, massage rooms, etc.) The next most important building is the kitchen/dining house. This is also a very large building, and it needs to be, because food is cooked for and served to hundreds of people at a time. When I was there, along with the 110 people who live there, there was also the 25 people volunteers for the week, a mantra seminar with a couple dozen people, and a communication workshop with another couple dozen. And during the camps (mainly in summer) that number is much higher again. These two buildings are the heart of ZEGG, and are constantly flowing with human energy. New people coming, going, staying. It’s a really nice energy, if you accept it. But it’s not always easy to accept – most modern people are used to lots of ‘me time’, time by ourselves, which can be difficult to find at ZEGG. At least my experience of ZEGG (which probably had sometime to do with sharing a large room with about 7 other people) was being almost constantly surrounded by other people.

Along with Uni, there were many different residencies, for both guests and community members. From cosy looking cottages, and trailers, to larger houses. During my week at ZEGG I was staying at the motel. This building was a bungalow with a kitchen, living room, a few bathrooms, and a couple of long sleeping quarters. The tight nature of the space meant we all quickly got to know each other and create a community feeling. In the summer there is also the option to sleep in large tents or wooden cabins on ‘tent square’. Other little places of shelter include the Waldhaus, a little house in the forest for ZEGG members who want to retreat from the world of humans and be surrounded by trees and birdsong. There are also a number of beautiful little wooden huts, which I was told function as Liebeszimmer (love rooms). As we will look at below, love and sexuality is an important topic for the community and to this end a few spaces have been created dedicated to this. Places with a romantic atmosphere, where people can be a bit away from the community, and be on ‘neutral territory’ – an important element in the practice of free love. So if you see shoes outside the love huts, do not enter. Fulfilling the same role is the Blaue Salon, a whole house dedicated to ‘sinnliche Liebe’.

Other important buildings include; San Diego, another seminar room/bar at the front of the site; the workshop, a huge, well organised, space to suit all your carpentry needs; the internet cafe, the only place on site with wifi. On Dorf Platz there was a number of cute little spaces. First was the Kneipe, which served as a cafe during the day and pub at night, and had a very warm energy – cushions everywhere and a huge stove made of glass (so you could see the fire) beside the bar. Right above that was Raum der Stille, a bright meditation room that is especially still first thing in the morning. Opposite this building is an arts and crafts shop where you can buy bits of ceramic or other things (often made on site at ZEGG). Also dotted around ZEGG are a number of roundhouses. They serve many functions, (bike storage, clay pizza oven, outdoor kitchen) that are nicely built clay and wood structures that add a touch of natural building to a site already overflowing with cool structures. The final indoor thing to mention is the amazing sauna complex, and its chill out attachment dubbed the Alhambra. The sauna itself could fit about 15-20 people and the Alhambra is has an Arabic bathhouse style. Composed of a lounging area, massage rooms, Liebeszimmer, and self service bar, the Alhambra is a luxurious way to relax after a long day working in the garden.

The garden is located across the road from where the rest of the ZEGG compound is. With this 1.5 hectares and a slightly bigger hectarage a bit further away from the compound, the garden team manages to produce about 65% of the fruit and vegetables consumed at ZEGG, and with 110 community members and thousands of guests each year, that is no mean feat. The garden, like many things at ZEGG, are designed according to the principles of permaculture. There is mixed planting of vegetables, and lots of trees around the garden that provide shade and hummus. A lot of work also goes into the rebuilding of the soil, which, like a lot of soil in north Germany, lacks hummus and is very sandy. Composting and the production of terra preta are two methods of improving the ground. Beside the garden is the Kläranlage (waste water system). All the water used at ZEGG stays within the compounds, being cleared by a plant based filtering system. After the large mass is filtered out by a normal filter, the rest is cleaned by reeds and willow trees. In a part of Germany that is becoming drier and drier, it is important to keep as much water in the region as possible, rather than flush it out to sea or to some other part of Germany to be filtered. On the other side of the waste water system is a field where horses are kept (to what end I’m not entirely sure).

All around ZEGG are a huge variety of wild and introduced flowers, herbs, and trees. Some of the herbs are edible and medicinal but what they mainly bring is colour, scent, life. Buzzy bees bumble through the air, finding their favourite flowers. Both the flowers and the bees are cared for by a very nice woman who explained to me the various medical properties of bee products, not just of honey, but also pollen, propolis, royal jelly, nectar, or wax. The largest open space at ZEGG is a huge square toward the back of the compound. The square has a very charged energy, and is overlooked by an old redbrick chimney. I’m not entirely sure what this chimney was originally for, or if it still has a function (it is at least attached to the wood burning central heating unit), but it gives the whole space a lick of old redbrink industry. Next to the square were the framework of two huge circus tents that are erected every May for the summer season, which is full of festivals. To chill out at ZEGG there are a variety of options. You can go for a walk in the forest (and most of the surrounding is forest), you can go for a swim in the pool, or, at night, you can get a bonfire going and sit under the stars. The space has been around for at least a century, and the people of ZEGG almost thirty years, and it really is a site to behold. So many big and little creations, so much peaceful nature (both human and non-human) sitting side by side.

Community

As

mentioned, about 110 people live in ZEGG, fifteen of those being

original members of the project since 1991, and about half of them

joining in the last five years. Another fifteen of this 110 are

children. The children all live with their parents but grow up in the

wider community structure. While not taking part in a lot of adult group

processes, the children do have a voice in the running of their lives.

One important element of this is the Kinderhaus, a building belonging to

the children to shape as they see fit. Along with the permanent members

there are another dozen or so short or medium term members of the

community, young people who come in the framework of an internship or

Freiwilliges Ökologisches Jahr (voluntary environmental year). These

temporary members of the community help to level out the generation gap

that exists in the community, as permanent members tend to be either

children or older, with the 20-35 year olds less represented.

This age gap is nothing unusual to the older, well established, communities and is the result of a number of factors. The first is that joining the community it is no easy process, and requires a lot of free time and money. While there is no entry fee to join the community, it is mandatory to do an intensive 5 week community course that costs 2000€. While it is perhaps an understandable price for 5 weeks of food, accommodation and full time teaching, it is a lot of money spend to take only the preparatory first step of joining the community. Even after this course, there is a number of other steps before you might be asked to join the community, first with the status of ‘guest’, then after another year as ‘new-member’. The whole process probably excludes most young people, as well other groups in society who don’t have a lot of time a money on their hands.

Another factor is that young Europeans like to travel, especially the ones who would be more inclined to join an eco-village. After spending most of the first 20 years of their lives in educational institutions, people want to use their new found freedom to explore the world, not settle down to something straight away. The high barrier to entry means that people who might want to stay for a few years, but not make a lifetime commitment, have no place. This is understandable from the side of the community, it is be difficult to build something concrete when people constantly up and leave, but this creates a lack of youth energy, the breath of life that keeps a project fresh. Often these larger communities start off with a strong impulse, to radical transform their own lives and wider society. But this is no easy task, radical transformation of our way of living is something that takes time and energy and doesn’t happen in a few days or weeks or even years. It is a constant process of reflection and practice.

After 20, 30, years of this its natural enough that this radical impulse for change wanes, that you become settled. Getting older often means you take your foot off the pedal and find contentment with what you have achieved. At this point it is up for the next generation, who have learned from the achievements and mistakes of the previous generation, to take up the mantle and continue with the task of social transformation. It is thus important that there is a new generation of youth with that same radical impulse within the project. This can sometimes bring tension between the old and the new but this is also something that should happen, lest the youth all rush forward without taking head of the lessons already learnt. While the trend in almost all of the older, well established, communities is that the average age rises after the initial period, some communities, such as Lebensgarten Steyerberg, are beginning to take active steps to bring more young people into the project, creating projects and programmes that facilitate young people coming and staying for a short periods.

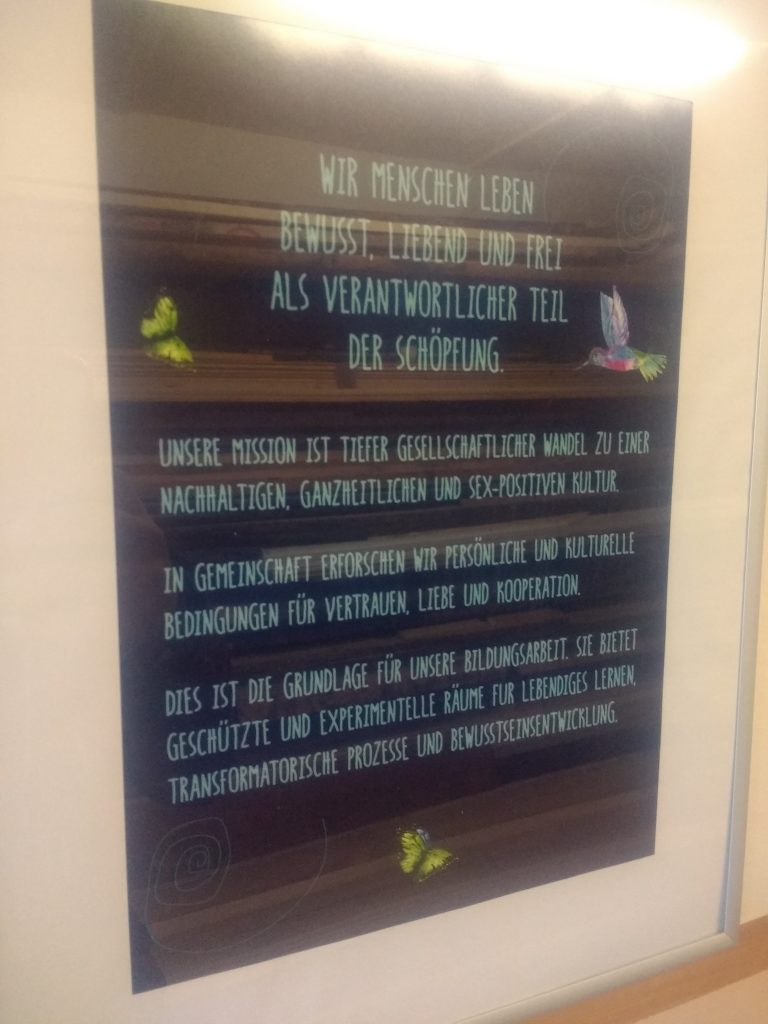

All this being said, despite the generation gap, there was still a very youthful energy in the air. All the community people that I met (as well as the guests) were very friendly and open, something that must be difficult when you have thousands of people coming to live with you every year. But being constantly surrounded by people is something that you have to expect moving into ZEGG because, from the beginning, the community was built around the Seminar Betrieb. It was originally founded, not just to transform the lives of the hundred or so people who were part of the community, but to change wider society as well. One of the various formulations of ZEGG’s mission statement reads; ‘Our mission is radical social transformation to a sustainable, holistic and sex positive culture. In community we are researching the personal and cultural conditions for trust, love and co-operation. This is the basis for for our courses. To offer safe and experimental spaces for experiential learning, transformative processes, and conscious development.’ The Seminar Betrieb is the link to the wider society, where people from outside the community can come and take part in the social experimentation and learn from the 30 years of experience in social experimentation that exists here at ZEGG.

Inspired by ZEGG, many communities have followed the same model, of a community centred around a Seminar Betrieb. Sometimes these elements exist side by side with one another, the community existing somewhat separately from the Seminar Betrieb, but at ZEGG the two elements are tightly interwoven. All the food from the garden goes to the seminar kitchen, most of the funds that make the community possible come from the seminars, most of the people employed by the community have work because of the seminars. Along with the various courses, which we will look at below, there are three or four ‘camps’ throughout the year. These camps are community festivals, 10 day long celebrations with music, workshops, food, etc. designed and built by everyone at ZEGG in a group creative process. All community members must work about 4 hours a day for the running of the camps. In this way the group have some measure of shared economy, they all work to keep the Seminar Betrieb going and the Seminar Betrieb makes their lives in the community possible. This is about the extent of the shared economy however, and, economically, all the community members are individual (or family) units. Those who work for the community are paid a wage, and to live and eat at the community costs about 600€ a month.

Social Techniques & Experimentation

As mentioned, ZEGG began and remains a centre of social experimentation, and man community members work to develop various techniques and frameworks by which humans can live in harmony with one another. Here we can look at some of these experiments and techniques.

Building Love, Trust & Respect

The most important of these techniques to the community, and the one that has spread the most widely, is das Forum. First developed in the forerunner project to ZEGG, Bauhütte, das Forum has spread out across Germany and further afield, becoming one of the most popular communication methods in the eco-village movement. The basic idea is that everyone sits in a big circle, one or two people moderate, and anyone who feels the impulse can go into the circle and ‘show themselves’ – speak whatever is on their mind. The understanding is that whatever a person reveals in the Forum is not to be talked about outside the Forum, helping people to open up. As the person is in the circle, everyone listens attentively and remembers ‘this is another person like me, and I should hear them with love and respect.’ While the circle is mainly there to listen, it is possible for one person to act as a ‘mirror’ – to offer an outside perspective on this person’s topic.

But Forum is not a solution orientated method, it is rather a way of making the different perspectives that exist in a group visible. This often leads to solutions further down the road, as clear communication is essential for any conflict resolution in the community, but this is not the role of the Forum itself. Forum is more to do with this element of social drama, a safe space for people to open their inner world up to the rest of the community. And in the Forum we had during one evening with the other volunteers, I could really see the effectiveness of the method. People who seemed otherwise shy or quiet used the opportunity to open themselves up to the group, revealing what was going on in their heads. And it was clear to me that this framework for communication and sharing contributed a lot to the inter-personal bonds, as well people feeling comfortable in themselves in the group context. There was no need of in our group, but I can also imagine the Forum would be very useful tool in conflict resolution, a central element of community building.

Forum was not the only method for forming social bonds and understanding. During the group times we engaged in many other types of activities. There were periods of deep listening, in which people in groups of two or three would talk on a particular topic, for example ‘what drives you at this moment in your life’. But instead of being a back and forth exchange, one person would talk for seven minutes uninterrupted. This was not only a good chance for people to develop their thoughts at their own pace, and learn something about others in the group, but also to develop the capacity of listening. Listening is one of the most important social tools we have, without listening there can be no mutual understanding, no co-operation. But the art of listening is not something that most people try and develop. Often people are too concerned with what they think, or what they want to say, to really listen to their interlocutor. The periods of deep listening are thus good practice for an essential skill in community building.

Another group process was, after walking around the room a bit, stop in front of a random person and look into their eyes. During this rather intense encounter, the person leading the exercise will ask you to say internally, ‘This is another person like me, with their own hopes, fears, histories. May they find peace and happiness in their lives’. The eyes are the window to the soul. When they meet an intimate connection is immediately established (which is why many people shy away from it). The exercise practices a dispossession of good will toward everyone you meet, even if they are strangers. Other types of group processes were various body exercises. Stretching, dancing, tapping, or falling (trust exercise) not only brings closeness and connection between people, but also mean that people stay in their bodies and don’t get sleepy during the periods of speaking.

Conflict Resolution & Decision Making

But

while these are all exercises for building feelings of love, trust, and

respect between people, by themselves they are not sufficient for the

successful functioning of a community. Because, even with the various

practices for building love and trust, conflicts do arise, and when they

do, you needs methods for dealing with them. As well as that, you need

methods for making group decisions. At ZEGG, like at many communities,

the methods for conflict resolution and group organisation come from the

fields of non-violent communication and sociocracy.

Non-violent communication (NVC) is a method first developed by Marshall Rosenberg in the late 1960’s. After working as a mediator between universities and rioting students, Rosenberg felt the need to develop a set of tools and principles for conflict resolution and peace making. Inspired by the civil rights movement in the US, as well as Mohatma Gandhi’s ahimsa (non-violence) based politics, the basics of NVC started to take shape. The basic assumption of NVC is that all people have the capacity for compassion and empathy and that we only resort to violence when they do not recognize more effective strategies for meeting needs. The various exercises of NVC are designed to encourage three aspects of communication; self-empathy (or self-awareness), being aware of your of feelings and sensations (although trying not to make judgements about them); empathy, trying to connect with and understand the other; and honest self-expression. The modes that are encouraged are of four types; observation (what you are seeing, hearing, touching), without trying to make sense of it; feelings, emotions or sensations (free of thought and story); needs, expressing what you need from the situation; requests, asking (without demanding) the other person for something concrete. A typical NVC way of expressing is something like – ‘When you do A , I feel B, because I want C. I would really appreciate it if you could do D.’ But these are just the basics, NVC goes much deeper, offering a holistic framework for group communication and conflict resolution.

While NVC is more orientated toward conflict resolution and a framework for mediating interpersonal relationships, sociocracy is more aimed at group decision making and designing or transforming social groups. It’s aim is to create harmonious social environments and effective organizations. The idea of sociocracy first arose from 19th century sociologists, who wanted to use the new science of social relations for the benefit of humanity. These sociologists, unhappy with the political competition of majority voting, believed they could use the new developed social sciences to improve modes of human organisation. Their aim was to develop a mode of decision making that improved upon the majority rule form of decision making that is found in most Liberal democracies, and so began developing a model based on consent (meaning all parties involved must be in agreement).

In the 20th century, Dutch sociologists further developed this idea, and began to develop practical methods. For an understanding of how the framework looks in practice we can look at a basic rundown of how sociocratic decisions are made; Everyone forms in a circle. There is sometimes a quick round where people say a few words about their current mood. There a concrete idea is proposed to the group. Then there is a ‘temperature check’ to get a feeling on how the group feels about the idea, consisting of hand signals meaning either ‘I agree’, ‘I have reservations’, or ‘I object’. Those with reservations or objections are heard. The person who is proposing the idea then has a chance to respond, and perhaps see if a compromise can be found. The idea is not that you have to be 100% happy with every decision, but it must at least be something that you can consent to. If not, then the person who has vetoed the plan should come up with another solution to the problem. This is a bare-bones description but it gives some idea of the decision making process.

This form of consent based decision making can be found in many of different groups within the field of eco-activism. From community projects, like Sunseed Desert Technology in Andalusia, to campaigns of civil disobedience, such as Ende Gelände or Free the Soil. During large climate actions with a lot of people, the methods have to be adapted somewhat. Its not practical, or even really possible to form hundreds of people into one big circle. In cases like these, the group forms smaller circles, where the plans and proposals can be discussed. When the group has come to some kind of understanding, they send a delegate to a larger circle, where the delegates represent the opinion of the group. This method worked very well when we had a bit of time on our hands. But when the topic was ‘should we stay and try and resist the police that are about to violently remove us from our position?’, things quickly descended into chaos.

I wasn’t there during any of the ZEGG decision making processes, but I was told that it is done according the methods of sociocracy. That most decisions are made in smaller groups (the garden team, kitchen team, etc.), but the bigger decisions on the community level. However, I was told that its difficult to always do things on a 100% consent basis. For example, one person from a group of 110 vetos someone becoming a new member. A decision like this naturally causes a lot of hurt on all sides.

Love and Sexuality

At ZEGG

the most important fields of human experience are that of love and

sexuality. What earned them a lot of infamy and attention in the

beginning was that ‘free love’ was one of the central values at ZEGG.

Free love is concept that emerged during the period of the

Enlightenment. The basic idea is that people should be free to love

whoever they please, without outside interference. What Enlightenment

thinkers were trying to ‘free’ love from, was the control of the Church

and State, who sought (and seek) to control the private relationships of

individuals. The free loved movement began as an attempt to transform

the socially accepted social norms around marriage, birth control, and

monogamy, among other social conventions. Percy Shelly was one early

advocate for free love and wrote;

I never was attached to that great sect,

Whose doctrine is, that each one should select

Out of the crowd a mistress or a friend,

And all the rest, though fair and wise, commend

To cold oblivion …

True love has this, different from gold and clay,

That to divide is not to take away.

Throughout the ages, the idea of ‘free love’ has inspired people in many different ways, in many different social contexts. For the pioneering feminist Mary Wollstonecraft it was about asserting the existence of female sexual desire, and its potential to be fulfilled outside the confines of marriage. For Friedrich Engels, it was about breaking the oppressive bonds of the nuclear family. For the queer movement, free love is about breaking love and sex from the bonds of normative sex and gender roles. It was at the end of the 1960’s that these idea and practices began to explode onto the mainstream. In the US, hippies congregated in Haight Ashbury in California and began challenging (among other things), the received sexual morals of American society on a mass scale. In Germany, those involved in 68er Bewegung were doing something similar. Kommune 1 was founded in Berlin, with the kommunards practising non-monogamous relationships, and experimenting with non-traditional modes of living. Their idea was that fascism arises from the nuclear family and so must be smashed to avoid a repeat of the Third Reich. It is from these developments, among others, that the Bauhütte movement, and eventually ZEGG arose. The idea of free love is something that is accepted and practised at ZEGG. The focus of free love here is, as in the hippie movement, about accepting other types of relationships than purely monogamous ones. So people may have a main partner but still have romantic relationships with others, or maybe there are three in a relationship, or however else people may what to express their love for each other.

As a short term guest, and not having done any of the courses on love or sexuality, I didn’t really get to learn of about the intricacies of the personal relations. However I was told that the general trend in the community of late is less experimentation, and more traditional two person relationships, #‘marriage seems to be back in fashion’. ‘10 years ago everyone was with everyone more or less, today it seems like people have their fixed relationship. At the summer camps back then, people were quick to the Blaue Salon (the love house), today people are a bit more cautious’. This seems natural enough as a project grows and transforms, new people come and old people go. But whatever the case may be with people’s personal relationships, there is certainly a place and an understanding for anyone who wants to experiment with non-traditional romantic relations at ZEGG.

However while it is easy to hold the values of free love, and believe that everyone should be free to love whom they please, in the real world, it often doesn’t work like that. People get jealous, or scared, or find it difficult to give themselves to another person. ‘Love isn’t a coincidence, but a capacity’. And it is the building of this capacity that much of the energy at ZEGG is dedicated to. ‘Our mission is to create models in which all people, with their diverse ways of loving, have a place. When it becomes difficult, or when people want to change the foundation of their relationships, we are there for each other. Love research groups (Liebesforschungsgruppen) meet regularly to support and enrich each other.’ Their personal experience in experimenting with romantic relationships are the basis of the courses they offer. Groups within ZEGG, such as the Liebesakademie (love academy), or Liebeskunstwerk (Love as a work of art) give courses on things such as; the ability to forgive, self-love as the basis for loving others, clear communication in relationships.

However, some aspects of the work that ZEGG does on the topic of love are not without controversy. Within some circles ZEGG is regarded with suspicion. In the past it even earned a few scathing diatribes from leftist critics, who labelled the project as ‘anti-emancipatory’. The brunt of the criticism is that some elements of ZEGG are ‘hetero-normative’ – that is to say they fit within the traditional understanding of gender and sexual relations. The argument is that, for a community that is focused around the topic of love and sexuality, queerness or homosexuality is fairly absent from the conversation. This is fact can be explained by the fact that the community is mainly made of straight people. But the question could therefore be raised – how is it that a community of people dedicated to radical forms of love has almost no gay or queer people? A text on the wall reads; ‘at the moment we are mainly heterosexuals, but we are happy with light impulses [zarte Ansätze] from queer life.’ This is a somehow strange formulation of the community philosophy on queerness; ZEGG is happy about a bit of queerness, but not too much (is at least how some people could read it).

Another thing that may be off putting for queer people is that other element of heteronormativity – traditional male/female gender roles. Because, like other fields that concern themselves with the spiritual elements of sexuality such as new age Tantra, there is a lot of talk of ‘male energy’ and ‘female energy’ – with the male energy often meaning active, dynamic energy, and female energy equated with passive, receiving, energy. To go with this are a few courses that would raise eyes in queer circles, such as the Intensive Men’s Training, in which men learn to access their inner masculinity. Their are also female only courses, such as Sources of Female Power, in which women come together in solidarity and learn about the their innate power (this would more acceptable in leftist circles as it is about empowering an oppressed group). But in general, there is sometimes a strong polarisation of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ – which jars with the queer and radical feminist understanding of ‘emancipation’ when it comes to love and sexuality, putting some people off ZEGG as a community.

This is a tricky topic to deal with, and not one that can really be properly elaborated or explored in a paragraph or two. Our society, like many human cultures throughout the world and throughout history, have been dominated by males. The patriarchal foundations of our society force people into positions of oppressor and oppressed, in which both men and women suffer. What’s more, strict normative prescription for how one should behave based on their sex is something that hinders self-expression, understanding, love, and diversity. But, as I experienced it, ZEGG is not a patriarchal space. The community is run on the basis of equality, and it goes without saying that this means equality between men and women. Some of the strongest personalities at ZEGG are women and the large variety of communication methods ensure that everyone has a voice. And while ZEGG is not a queer space, it is certainly open and accepting of queer people. On the entrances to the male and female toilets is a sign saying ‘*and Trans, intersex, and non-binary’, and to go with the ‘men’s circles’ and ‘women’s circles’, which regularly take place, are the ‘people’s circles’.

The question is then, is the teaching of gender roles in itself ‘anti-emancipatory’? Or was the problem more to do with the inequality and oppression in our (and many other cultures) division of men and women? Surely the goal of queer struggle is that people should be free to choose their own gender identity, including cis- straight people? And if people do feel happy identifying as a man, then it is surely good that people try and develop positive models and examples for what it is to be a man. I didn’t do any of the courses, but from the description it seems to be about learning to communicate better, respect women, and not repress your emotions (along with the more traditional masculine traits of decisiveness, mental fortitude, etc.). This is surely a welcome counter-balance to many other socialising agents, which teach a toxic kind of masculinity. I guess there’s not really a right or wrong answer for whether or not gender roles are a good or bad thing. For some people they work, for others, not. What’s important is that the person themselves gets to decide what role they play, and is not forced into it through methods of repression. What this requires is a measure of self-reflection from everyone, and an effort on all sides to make sure everyone feels comfortable to express themselves in whatever way they please.

Fin

The influence that ZEGG has had on the German eco-village movement is not to be understated. Many of the things that made ZEGG a pioneering place in the early 90’s (the various communication techniques, non-traditional relationships, ecologically based ways of living) are now becoming fairly standard, but all these elements made ZEGG a pretty radical place in the 90’s. Today ZEGG is still a model for a well functioning community and a great place to learn about various methods of community building, and improving your capacity for love.

For more information: https://www.zegg.de