After a couple of weeks in Lebensgut Cobstädt it turned out some people were heading to the GEN Deutschland meeting in Lebensgarten Steyerberg. Lebensgarten is considered one of the first eco-villages in Germany, and so I already had it in mind to pay a visit. Happy at the fortuity of events, we all loaded into the car for a four hour journey from middle Thüringen to Niedersachsen. With the GEN on in the first week of my stay, I didn’t have much chance to learn about Lebensgarten, but the following weeks gave me chance to experience life at the community.

History

The history of the settlement that the community finds itself on long predates the history of Lebensgarten Steyerberg, and goes back to the darkest recesses of Germany’s past. Constructed as an attachment to a gunpowder mill by the Nazi’s in 1939, the village was originally populated by people shipped in from Ukraine, Italy, Poland and the Netherlands. After the invasion of Russia it was often exhausted Soviet prisoners of war who were shipped in, forced to work for the Nazi war machine. In 1945 the British army took control of the space, and from that time until 1983, the site had various functions. It acted as an army storage for the British occupying force. It was a refugee camp for the Russian prisoners of war (who were often seen as collaborators back in their home country). The dark history of the site is not one that the community is hiding away from. They see part of their mission as healing the dark energy of this space, and have held many healing ceremonies trying to deal with what went on here. A few years ago, the community invited some former residents back to see how their village had changed, and ask what they could go to commemorate the suffering that happened here. In reply they were told that the most important thing was merely to make sure people knew what happened there, not to hide it from view.

In 1983 the space was acquired by Christian Benzin, a young West Berliner from a wealthy family. Inspired by a trip to Findhorn in Scotland, he sent the call out around Germany for people to join a new type of ecologically and spirituality, orientated community. By 1985 there was a group of about 7 families who had come together with a shared vision and began with the task of building a community. During the decades of British occupation, most of the houses had fallen into disrepair. When these pioneers moved on site only one house was habitable, and so the first thing on the agenda was the creation of living space. However this was not the only thing on the agenda. In 1985 the community opened a seminar house where they would start offering courses on things such as permaculture or non-violent communication. 1986 saw the opening of the Zen temple by Zen master Oi Saidan Roshi from Kyoto, as well as the foundation of the Permaculture Institute of Europe by Margrit and Declan Kennedy. In 1990 the Schule für Verständigung und Mediation (School for Understanding and Mediation) became another important feature of the community. And these are just projects from the early period. Over the proceeding decades the community would give rise to dozens of different ecological, spiritual or socially oriented projects, organisations, and businesses. And Lebensgarten is showing no signs of slowing down in this regard. In the final section we will look at some of the projects currently underway in the community.

One particularly important event in the history of the community is when it acted as one of the external exhibitions of the World’s Fair, which in 2000 took place in the near by city of Hanover. The World’s Fair is an event that goes back to the Victorian era and are essentially big exhibitions in which countries from around the world, show off different elements of their culture or technology. When it was announced that there would be external exhibitions during the fair in Hanover, Lebensgarten applied as an example of a model sustainable village. To their great surprise, their application was accepted, and thus received a large grant to renovate the community building. The World’s Fair gave a lot of impetuous to the reconstruction efforts, and it was in this time that the village as it is today really started to take shape.

Community Structure

At the present moment, as most Lebensgärtner would attest to, there isn’t such a unified community consciousness. The people of Lebensgarten don’t really think or plan as a single unit. While there are a few WG’s, most people live in their own houses – existing as individuals, or as a family unit. There is a plenum where people come together and talk about group issues, and there are regular community events and projects that bring people together, but a community consciousness built around a feeling of shared destiny, didn’t appear to be so strong at Lebensgarten. My impression was of a group of like minded individuals and families who have come together to support one another, but on an individual basis rather than trying and develop strong community institutions. There is no doubt a common purpose that has brought this community together, but this common purpose is not really pursued on the community level. Essentially all of the projects run by the Lebensgärtener have been set up as Vereine or gGmbHs. This means they exist somewhat separately from Lebensgarten, being run as businesses or NGO’s from indivduals within the community. There is also an underlying set of community values, to live spiritually and ecologically, but its not really clearly defined what that means. There is apparently a document that exists somewhere in the community archives with a clear community mission statement and set of values, although no one who I asked seemed too sure of what was in this document.

Because the plenums are closed, it was difficult to get a real feeling of the current community dynamics. That being said, there does seem to be a movement of new, younger, members who want to change things at Lebensgarten. To move away from the more individual, business orientated, organisational structures; to a more community orientated, non-commercial model. The idea is that the many projects in Lebensgarten that currently operate as businesses, stop operating as profit making businesses, and start operating more to a logic of shared economy; that the community acts more to meet its own needs, rather than fitting itself into the global economy. This would obviously mean a huge reorientation, not only on a community level, but also a personal one. We have all gotten very used to the luxuries provided by our global system; new cars, the ability to fly all over the world for holidays, flashy new gadgets, etc. To convince people that community empowerment and ethical living is more rewarding than the commodities and lifestyle they have grown accustomed to is not easy. This is undoubtedly the most difficult challenge facing the environmental and social justice movements in the coming decades. How to inspire people to wilfully give up all the luxuries they now take for granted? If this question finds no answer then we are destined to push this world to the limits of its capacity to be exploited, and these changes will instead be foisted upon us, in far more unfavourable circumstances then if we freely accede to them.

Having said all this, there are advantages to the loose community structure at Lebensgarten. One is that it makes it a much more accessible community for most people in modern society who have been socialised as individuals or as part of a nuclear families. A community consciousness is something quite alien for many in modern society. People have gotten very used to existing as individuals, thinking and acting as individuals, and so becoming part of a community is something that is provokes resistance. Although this individualist mindset often causes loneliness, selfishness, anxiety, and existential dread, it is something that is hard to give up on. Modern society necessitates this way of being. Once you reach adulthood, you come to the realisation that the only person who will really look out for you, is you. The individualistic ego is thus a survival instinct bourne of an individualistic society. For people to give up on this instinct, to trust in the world, to once again trust in other people, is not easy. Communities that still operate according to a more individualistic (or nuclear family) logic, but are going in a better direction, are important bridges between our modern individualistic society and our community orientated future.

Space

The village is composed of about 60 individual houses, as well as various community spaces. The layout of the settlement is largely the same as it was during the time of its construction, but, as the various before and after pictures can attest to, the reconstruction process has given the village a very different feel. While the pictures of the original village has the artificial feeling of centrally planned settlement, the village is now is full of life, abounding with a revitalised nature and many signs of the joy of human creation and recreation. While most the houses are still the same redbrick constructions of the 30’s, they have been retrofitted to be as sustainable as possible; underground heating systems, insulation, solar panels. Adding to the feeling of new life are the revitalised gardens and greenhouses that hug the semi detached homes. These houses are mainly assembled along a long road that leads into Dorf Platz, the village square, where the main community building can be found.

This community building is made up of various elements. When entering the building from the west wing you’ll first find the Lädi, a grocery shop, co-owned by the people in Lebensgarten. To buy things at the shop you have to become a member (or co-owner), giving you access to organic and bio-dynamic goods at cost price. Also in this end is the Zendo, the Zen temple erected by the Choko Sangha, where one can join group meditation and drink tea every morning. The centre of the building is composed of two largest rooms, huge halls that can comfortably host large events. It is these room where most the seminars take place (as well as hosting the GEN Deutschland meeting). Supporting these seminar rooms are a large kitchen and extra workshop spaces. Aside from seminar rooms, the main building has two small shops; one a little gift shop where you can buy some of the various things produced by the people at Lebensgarten, as well as speciality coffee and massages; the other a music shop with a beautiful assortment of instruments from all over the world. Behind these shops is the Kulturküche (culture kitchen), another smaller, cosier, seminar and community space. Below this is a intimate space that’s a café on Sunday afternoons and a pub on Friday and Sunday evenings. Finally, on the southern end of the main building you have the Kapelle (chapel), a beautiful little chapel space that hosts mantra singing, and burial ceremonies.

Aside from the building there are some outdoor feature at Lebensgarten which are worth mentioning. The Heilhain (healing grove) is a beautiful space at the entrance to the forest. This space is filled tipis, stone labyrinths, fire pits, and wooden frames which sometimes come alive during sweat lodge ceremonies, all located between young oak and birch trees. The large forest that the Heilhain leads into is only partly on Lebensgarten land. This was a huge mono-cultural pine forest when first taken over. But the part that are in the hands of the Lebensgärtener is slowly being transformed into a mix forest, and is definitely more alive than the usual mono-cultural commercial forest. When I was there, the middle of autumn, there was a variety of tasty edible mushrooms. The bay boletus, chicken of the woods, charcoal burner, and bare-toothed russula could all be found, digesting the forest left-overs, before becoming a part of another digestion process inside my belly.

The final part of the space at Lebensgarten which I will describe isn’t officially a part of Lebensgarten at all, rather it belongs to the gGmbH PALS (Permaculture Association Lebensgarten Steyerberg), but unofficially it is very much a part of the space and so it’s worth a mention here. The PALS area is made of two main spaces. On the side closest to the village you have the permaculture gardens, where most of the vegetable production takes place. Aside from the vegetable beds (mainly filled with brassicas when I was there), there were quite a few greenhouses, raspberry bushes, patches filled with autumn wild herbs, as well as an area with chickens. This gardens are able to fill 60 boxs with vegetables each week. In a model similar to Community Supported Agriculture, people from the village and local area have a subscription and come pick up these boxes once a week.

The other half of PALS was more people oriented. At the centre was a spacious fields, with an original Mongolia Yurt, and as well as a wooden dome to host people who come for courses on Permaculture. Once a year, this space comes alive with a thousand people for the festival Samana. Right now occupied by people not a part Lebensgarden, but living in a happy collaboration with PALS. These people build festivals, and needed a space to live in between time, which is what they are doing in Lebensgarten. When I was there there were building Lebensgarten a barn for some alpacas that needed a home, as well as buildings a sauna, spa area, and afterwards they would play a leading role in building the Samana festival. Apparently, there some concerns in the beginning about the relations between this group, and the people from Lebensgarten. The festival builders lead very different lifestyles than those found in the eco-village; with late night parties, weed, beer, and BBQ’s. A Lebensgartener said this was a funny turnaround from the days when they were the strange band of people at the edge of town, freaking out the locals who imagine the worst of what is going on there. Although a nice observation, it is somewhat exaggerated – and to me it seemed like the two groups were living in happy symbiosis.

Declan Kennedy

One of the founders of Lebensgarten is Declan Kennedy. As it turns out, he was a good friend of my aunty, and most of time at Lebensgarten I stayed as his guest. As he is such an interesting character, it is worth recounting a few details here. Born in Ireland in the 1930’s, he left the Fair Isle in the 50’s to pursue a career as a university professor of architecture. Although he and his wife Margaret would be somewhat seen as outsiders in conservative university circles, he achieved a level of success on his chosen career path, and was voted vice president of the department at the Technische Üniversität Berlin. Despite this, when he was in his 50’s, himself and Margaret left Berlin to pursue what he called his ‘second life’. During this second life Declan would live three landmark events for the global eco-village movement.

The first is being one of the founders of one of the first eco-villages in Germany. Declan was one of original group that in 1984 came together to create a community a new kind of community. The second was bringing permaculture to Europe. Now central pillar of the eco-village movement, permaculture is as a global movement in its own right. Essentially consisting of a set of design principles for designing sustainable types of human settlements and agriculture – the knowledge and practice behind these principles are transmitted through the Permaculture Design Course (PDC). Declan did one of the very first of these courses with Bill Mollison in Australia. Having completed the PDC, he returned to Europe and began spreading the knowledge of permaculture across the continent. The final landmark event we can mention is that he one of the founders of the Global Eco-Village Network (GEN).

Now 85, Declan cuts a sprightly figure and leads an incredibly active life. During my time in Lebensgarten he was always travelling between environmental conferences and family parties. He would be up in the early hours to lead circle dances, and, if he had guests, stay up to the earlier hours drinking wine and whiskey. When he was at home he was almost always entertaining guests, and was constantly telling stories or sharing ideas. To write about everything talked about in those few weeks would require a multi-volume book, but a few examples would serve to give some idea. He talked a lot of practical ideas related to architecture and agriculture. One idea that he mentioned a few times was working with the electromagnetic fields of the earth. For instance, he set up his office according to water veins running under the earth – these being points of higher energy that people, conscious or not, tap into. A technique which he has been experimenting with in the garden is planting rebar in the ground along the north/south axis, in order to conduct the electromagnet energy flowing between. He maintains that this heats up the ground by one or two degrees, encouraging the growth of microorganisms and allows for a slightly longer growing season.

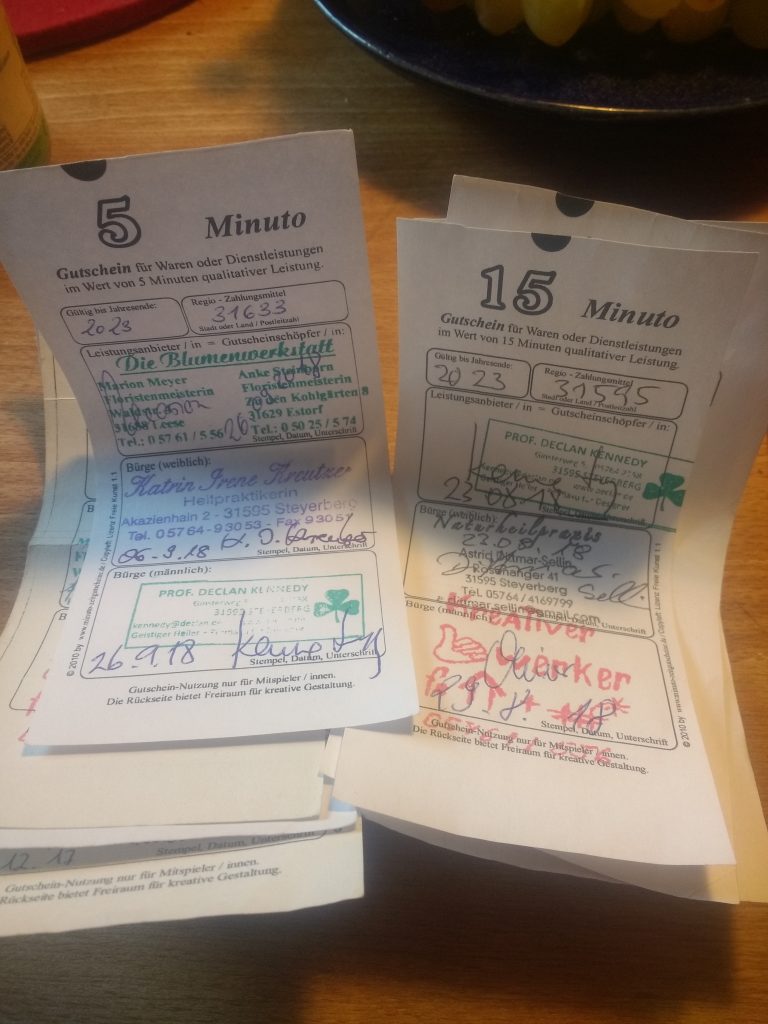

He talked a lot of his wife, Margrit Kennedy, who died in 2013. Margrit is also an important figure in the history of eco-village movement, as well being an important advocate for alternatives to our current system of money. Her vision was the creation of a system of exchange not based interest and inflation. In Lebensgarten there was a local currency, the minuto, with which people can trade goods or services by writing their own bills of exchange (guaranteed by two others in the system). This didn’t seem to be widely in use but it was interesting to see experiments in alternate system of currency taking place.

‘What do you see as the next step for GEN?’ I asked him one evening. This question didn’t seem to land straight away so I continued ‘right now eco-villages are a movement happening at the edge of society, how would it be possible to turn it into a mass movement?’ ‘There is no one answer to that question,’ he said, ‘right now there are many different things tendencies coming together.’ But after letting the conversation to flow for another while I felt I somehow got an answer to this question. ‘The second stage of the GEN movement is the eco-villages working to empower the villages in their surroundings. Turning all villages into eco-villages, without everyone having to found new communities. This comes from the people in Cameroon and Senegal. They told the local government not to give money to eco-villages, but to give money to all the villages to be more ecological. This is had great success and then it was like all the villages started becoming eco-villages. That’s what great with a global movement, you can learn from people all over the world’.

Projects & Pursuits

Although there are not so many community projects at Lebensgarten, that does not mean there is not projects in the community. Quite the opposite. There is more going on then you can get your head around. From one off or weekly events, to larger organisations and initiatives, there is no shortage of things to do when spending a bit of time at Lebensgarten. I’ve already mentioned some, and I won’t go through everything, but I can talk of a few of the different things were happening during my time there.

Like many of the bigger eco-villages, one of the main economic engines is the Seminar Betrieb. Here the people of Lebensgarten, as well as people from outside the community, can avail of a large selection of courses; mediation, meditation, singing, dancing, yoga, or similar things. All the seminars take place in the main houses, and the guests mainly stay in the Heilhaus. While the Seminar Betreib is the main connection with the outside world, being the main reason for people to come into the community, I got in the feeling that it was somehow a little separate from the community. Most the courses went on relatively unbeknownst to the community memebers that I was spending my time with, and if they wanted to use the spaces belonging to the Seminar Betrieb, they had to pay money. What’s more, for reasons unknown to me, the Seminar Betrieb buys its food from outside the community, rather than from the permaculture garden on site. It is things like this which show that a lot of elements of Lebensgarten function alongside one another, rather than operating as a single unit.

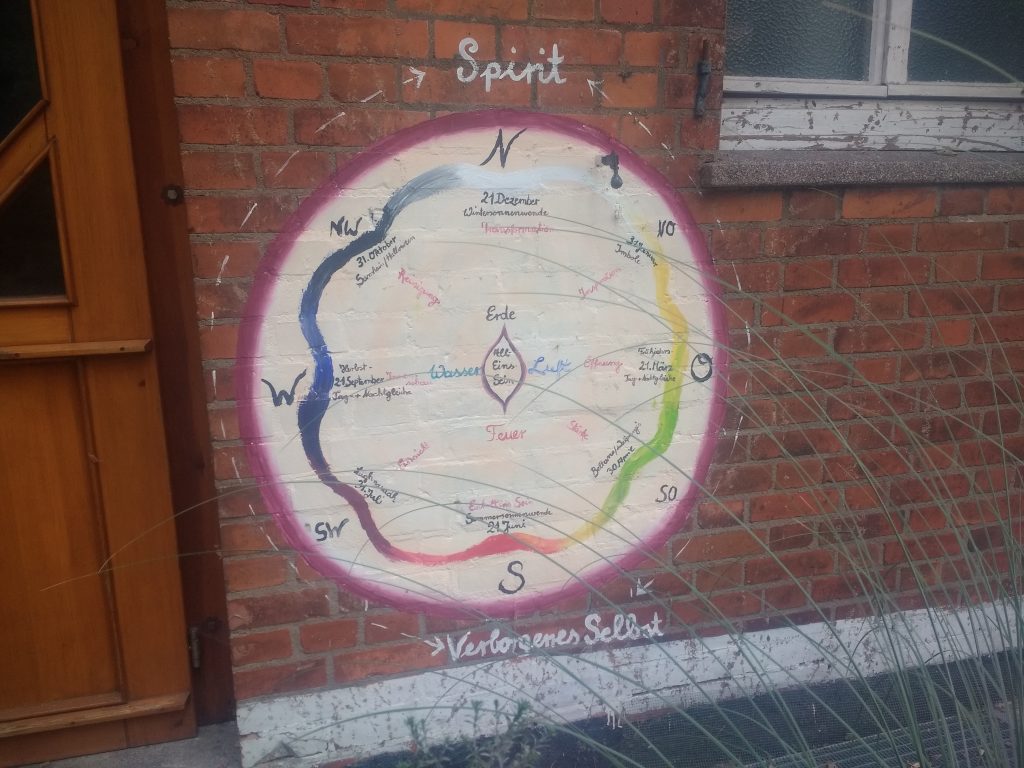

In Lebensgarten there are a number of people who have begun bringing neo-shamanism practices to the community. So at different points of the year, important seasonal and cosmological events are marked with specialised rituals. My time in Lebensgarten coincided with Samhain, the Celtic new year. Samhain was on the most important dates in the pagan Celtic calender and many passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with its coming. Growing up Samhain was my favourite festival, and so I was happy to see that the occasion was marked by the community. The ceremony took place in the yurt, a beautiful space built in the original style by a visiting Mongolian family. Samhain, as the passing from Summer to Winter, light into dark, is a liminal time, when the spirits had greater access to the world of the living. A lot of the ceremony was in celebration of our ancestors, an attempt to connect with those who had become before us. It was also a time to get in touch with the world that was undergoing transformation, the four elements, the six directions. In modern times, most of our celebrations, rituals and ceremonies, centre around consumerism, or, at best, the family. But these occasions can be something more. They are opportunities to take a step back from the day to day and get in touch with the wider cosmos which we are generally unaware of.

One project that is very important for bring the community together is the community meals cooked by Kaya, one of the residents. Food being one of the main ways that a community comes together, it is good that someone has taken it upon themselves to cook something for the community everyday. While not all 150 Lebensgärtener come together to eat everyday, throughout the week you’ll get the opportunity to meet with a lot of community members. The kitchen itself is run on a few ethical principles; no plastic, vegan, all organic, regional, and seasonal (with a lot of the food coming from PALS). I found it great that someone was putting in such an effort in the kitchen. Many communities do a lot in the garden, but still eat a lot according to their old habits – imported, non-seasonal foods. We have gotten very used to eating what we want, when we want it, but such a practice cannot be sustained for long. It makes no sense to ship our food from the other side of the world when we can provide what we need from our immediate surroundings. The reason we do so is for the subjective perceptions of taste. But we have to ask ourselves, now that we know the consequences, is it worth it? Is it right to poison the earth to satisfy our taste buds? Our perception of taste is malleable, we like what we are used to eating. So perhaps its time to bring our tastebuds more in line with a healthy earth.

Another project is the T36, a house project set up in the last couple of years. This house acts as both a public community space, as well as an entry point for people who want to come and spend time at the community. In the house there are spaces to sleep, an office space for people to work during the day and chill in evening, and a Heilraum – a nice simple space where people can do yoga, play music etc. For a small donation you can stay with all the food and facilities (including cooked meals) art your disposal. The people who run this house are very friendly, and there is always different people coming and going – every day bringing random encounters with people on all different kinds of journeys. This houses plays a vital function in Lebensgarten by bringing in a lot of youth energy. For various reasons, bigger and older eco-villages are generally peopled by the old and very young, with a gap of people from 20 – 35. T36, with its loose and accommodating atmosphere, provides a space that is more appealing to young adults to come and spend a bit of time. Another project for bringing young people to the community is Orientas. The aim of this project is to provide space for provided for young people to come and live in the community for one year, and giving support for them to develop and realise personal projects.

These are just some of the different things going on in Lebensgarten. The longer you stay the more you realise is happening. Everyday of the week there is different events going on; yoga, kung fu, circle dances, mantra circles, contact dancing. In the colder months you can heat up the clay sauna. On auspicious evening there are sweat lodges that take place. There are also people who offer all kinds of massages. So while there are not so many community projects or activities, in which everybody takes part, this has allowed the space for a huge variety of individual pursuits and projects, which other people in the community can than join when the impulse takes them.

One final I’ll mention is that these community spaces are great places for people with non-normative thought structures (learning difficulties, etc.). At Lebensgarten there was one young man who was particularly open hearted. The logic of his thought was definitely different to our normative standard, and his emotional intelligence was such that he would probably find it difficult to pick up on bad intentions. This kind naive trust in the world is dangerous in big cities as he could easily be exploited. But at the village he was safe and happy and had a very active social life. Modern society has a habit of singling people like out, bringing them into a medical apparatus where they live their lives according to a psychiatric understanding of ‘disorder’. But it is only a disorder from the normative perspective of the capitalist workspace. In a community people with all different kind of perspectives on the world can find a place. This young man played an important role in the village. He brought a feeling of trust in the world, and joy at the simple pleasures of life where ever he went. ‘Normal’ people often lose sight of these things, and so having someone with an eye on the essential is a pivotal role to play in a community.

For more information: https://www.lebensgarten.de/